Mohan Maghwar, 35, lives with his wife and three children of seven & five years while little one is of three months old, in the remote village of Rantnor, located in the Thar Desertⁱ in the south of Pakistan. All kinds of natural life here is dependent on the annual rainwater. Rantnor is deprived of most basic survival facilities including healthcare, electricity, clean drinking water or sufficient livelihood sources.

Earning an income through traditional Sindhi cap weaving and manufacturing, Mohan was the sole breadwinner for his growing family. His wife would also help him with the weaving. He would receive many orders from the local markets and neighbouring buyers for which Mohan would buy raw materials and work on a fortnightly basis and then sell the finished product providing him a comfortable means to sustain his family. However, as COVID-19 struck the country, he soon lost his only source of livelihood.

“Our lives were going fine before the coronavirus came in the country and the national lockdown was imposed. Before the pandemic, I was earning up to PKR 600 (approx. USD 4) on every cap my wife and I produced. Sadly, our work was suspended because of closure of markets and restrictions on gatherings. There were no orders to work on and no money to earn due to limited or no work opportunities. I was worried about making ends meet without any source of income.”

As a humanitarian response to the COVID-19 crisis, Community World Service Asia (CWSA), with support of United Methodist Committee on Relief (UMCOR), is implementing a project addressing the immediate needs of drought affected communities in Umerkot. Through the project, 1,206 families will be provided with two cash grants, each of PKR 12,000 (approx. USD $ 75/-) in September through mobile cash transfer services. This cash assistance is aimed at addressing the food insecurity caused by drought, repeated locust-attacks and the economic implications of COVID-19 on the most vulnerable communities in remote areas of Sindh.

Rantnor was among the project’s target villages due as the family’s livelihoods was severely affected by the lockdown amid COVID-19 and drought. CWSA’s team identified Mohan and his family as project pariticpant of this humanitarian response as they were most affected by not only COVID-19 but other natural and climate induced crises as well. Mohan received two rounds of cash assistances of PKR 12000 each (Approx. USD 75) in August and October 2020.

“With the money received, I purchased groceries and invested some money in a business and established a small enterprise shop at home, as I have marketing experience and utilized the cash assistance in creating a livelihood opportunity.”

ⁱ 55kilometers from Pakistan’s Umerkot District

Dr. Mohammad Shafi, a doctor and development practitioner with over two decades of experience in the social welfare sector, participated in a training titled “Influencing Positive Change” organised by Community World Service Asia under its Capacity Enhancement Program. The program aims to strengthen the capacity of local humanitarian and development workers on organizational, programmatic and technical skills while responding to the needs of the most vulnerable in Pakistan.

The “Influencing Positive Change” training was conducted in December 2019 and was participated by twenty-one aid and development workers representing twelve civil society organisations (CSOs) from across Pakistan. During the five-day training, participants strengthened their knowledge and skills on developing strategic approaches to policy engagement and designing campaigns for social change through policy reforms.

Employed with Brooke Hospital for Animals Pakistan since 1997 as a Regional Manager, Dr. Mohammad Shafi has been working for the welfare of horses, mules and donkeys engaged in intensive labour work of the many thousands of people and communities dependent on their service.

“I monitor and mentor the field activities of the project teams. I also work to ensure animal welfare, community development and monitor proper planning of capacity enhancement activities of the communities we work with in coordination with key stakeholders.”

“Our company was well aware of the good quality and value of the workshops conducted by Community World Service Asia in various operational fields for local and national organisations. Upon hearing of this training on ‘Influencing Positive Change’, I showed immediate interest and applied as a participant. The session on engaging with decision makers, as part of the training, was something new and interesting for me as it provided thorough knowledge on different advocacy strategies and tools for effective engagement with various stakeholders. The group exercise on stakeholders mapping was also very informative and a rich learning experience. After the trainings, I replicated the same exercise in mapping joint ventures when we planned the signing of a MoU with one of partners, the Bahauddin Zakariya University. We successfully signed the MoU on September 1, 2020.”

The significance and value of objective setting and identifying key stakeholders and influencers prior to the implementation of a campaign was another key highlight of the training.

“We are now able to define priorities for our organizational awareness-building activities. In terms of improved comprehension and application of science, we appear to have more effective outcomes now. We have started working with relevant partners, with whom we can collaborate together on promoting equine health. We also successfully signed a MoU with the Bahauddin Zakariya University (BZU) to strengthen equine health and welfare knowledge and skills of Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) students and allied domain. This MoU will fortify the role of veterinary science facilities of BZU as the hub for animal welfare excellence and encourage animal welfare.”

Shafi said that the pre-preparation assignments conducted during the training helped the organisation’s teams to examine and obtain relevant knowledge about the partners with whom they want to work.

“A comprehensive research before our meetings allowed us to convince relevant stakeholders more effectively in order to agree on common grounds for joint ventures,” expressed Shafi

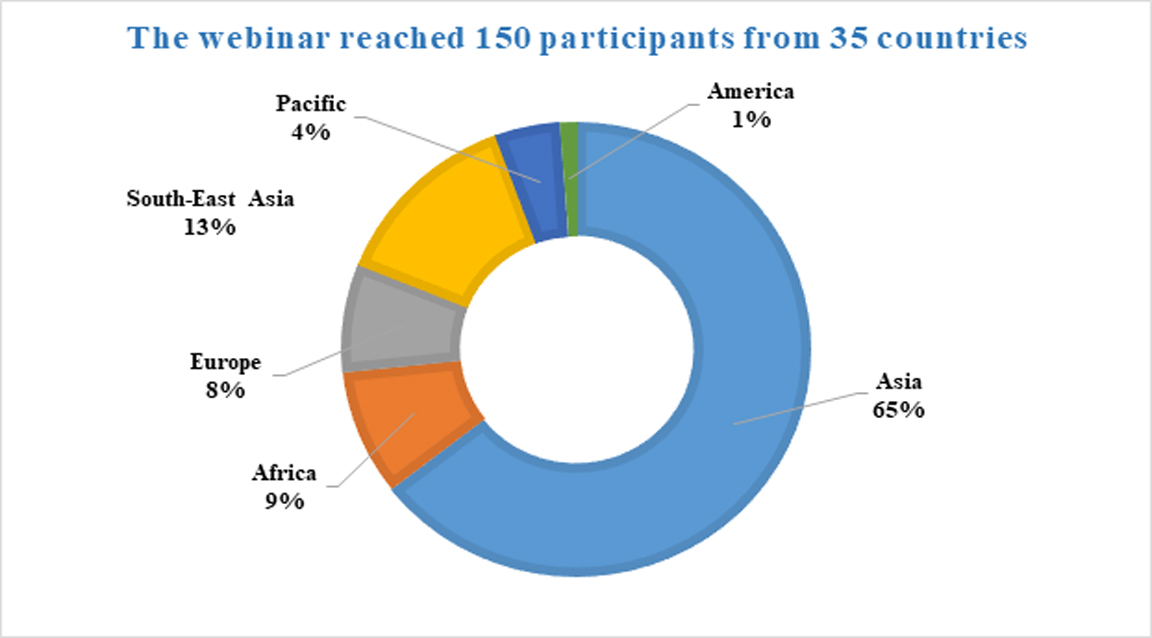

Quality and Accountability mainstreaming includes promoting and sustaining greater accountability to affected populations and to ensure its effectiveness, changes are required at different levels in the organisation. Hosted and organised by Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network’s (ADRRN) Quality and Accountability (Q&A) Hub as part of the 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events[1], a virtual panel discussion held on December 14th, explored the different levels and ways of mainstreaming accountability.

| Opening Remark | Shama Mall, Regional Director (Acting) |

| Moderator | Uma Narayanan, Independent Consultant |

| Panelists | Mayfourth D. Luneta, Deputy Executive Director, Center for Disaster Preparedness (CDP) |

| Hiroaki Higuchi, Manager of Program Development Division/M&E division, Japan Platform | |

| Coleen Heemskerk, International Director of Strategic Planning, Act church of Sweden. | |

| Participation | 92 humanitarian practitioners from around the world |

“Like for many of you, it’s very important for us that during any response or longer-term engagement, the affected communities are treated with dignity, and they fully participate in the process and hold us to account. Mainstreaming is not a onetime process; rather it is a continuous process. Commitment towards accountability and mainstreaming in our experience means leadership Buy-in, willingness to change behaviors and meaningful engagement and participation at community level,” said Shama Mall from Community World Service Asia, during the introduction of the virtual event.

Accountability: A Way of Life

Mayfourth D. Luneta emphasised on not just being accountable in policy but to walk the talk as a key indicator of having better services for communities. Center for Disaster Preparedness’s (CDP) vision is to establish safe, resilient and development communities and they work towards that by empowering and strengthening the people in the community for disaster risk reduction and management.

Organisations must engage in constant consultations and interactions with the communities to ensure to efficient programming and accountability processes. Mayfourth further shared,

“In communities we serve, we adopted different methods to keep a check on how CDP is working with the target affected populations. We mainstreamed these methodologies in our projects to monitor our workings whether or not the project required feedback or MEAL[1] planning. One of the tools known as The Evaluation Tree was carried out during the implementation of projects where community members provided continuous feedback on project activities, strategies, results at individual and community level, facilitating and hindering factors and recommendations. By doing this, we are being mindful of how we deal with our communities.”

How do we promote accountability with our partners and governments?

Organisations must continue to advocate and share lessons learnt with the government and relevant stakeholders for them to improve government programs by applying this data taken from the communities. CDC shared its example of The Inclusive Data Management System for Persons with Disabilities project that promotes the inclusion of persons with disabilities in planning, budgeting, and other development processes of local government and agencies, particularly in Disaster Risk Reduction Management (DRRM). The intended outcome of the project is to increase the capacity of local governments to capture specific information on persons with disabilities in their localities.

“This project collects and records information on disability and DRRM through using the Kobo Collect, an open source Android application used in primary data collection for challenging environments. Ultimately, the intended output of the project is the establishment of a comprehensive data management system for persons with disabilities at the municipal or city level. This project is at its finalization stage and the report will be then shared in the near future,” shared Mayfourth.

Quality & Accountability: Donor Perception

Hiroaki Higuchi discussed the limitations of reporting around accountability to donors and project participants. Typically reporting systems provide donors with a written account comprising of information in a form that ensures that the funds donated are used for specifically intended and planned purposes. This is usually in the form of a one-way flow of information from the NGO to the donor, with the focus being on the efficiency with which the donors’ funds have been spent. In some cases, reporting formats often appear inflexible and rarely reflect the voice and experiences of field officers and communities in the field.

There is a predominant belief that many donors simply use quantified metrics and undermine other valuable qualifications and explanations of local conditions contained in the accompanying narrative.

“There must be somethings behind the quantitative performance indicators that can reflect the overall impact of an NGO’s work by the Qualitative performance indicators. To address this issue, I recommend that there be a mixture of quantitative and qualitative performance indicators. A further recommendation in this area is to allow debates and discussions with NGO workers in the field and communities to help and determine appropriate performance indicators for specific project,” said Hiroaki.

One of the drawbacks of accountability mechanisms is that donors are not informed about the unintended consequences and failures in aspects of project delivery. NGOs often find it challenging to report on such outputs as there is not much flexibility in terms of reporting formats and scope. Hiroaki added, “There can be reluctance on the donors’ part or on the part of NGO to report unintended consequences or failures. In some cases, NGOs prefer to emphasise on the success rather than the failures in humanitarian projects. I believe in the longer term, these failures can help organisations learn and ensure more sustainable development by recognising and responding to the cause of a short-term failure. Furthermore, reporting of unintended consequences in aspects of project delivery is important as it provides an opportunity to inform donors about what kinds of difficulties the NGOs face on the ground in the field level.”

Ensuring Quality and Accountability at an Organisational Level

Following the example of ACT Church of Sweden (CoS), organisations can effectively mainstream quality and accountability through working towards commitments underlined by the Core Humanitarian Standards (CHS):

“We became CHS certified to ensure the affected-communities are at the center of our work. We want to ensure that we have to implement with the commitments we have made as an organisation. We, as an organisation, want to commit to continue learning,” remarked Coleen.

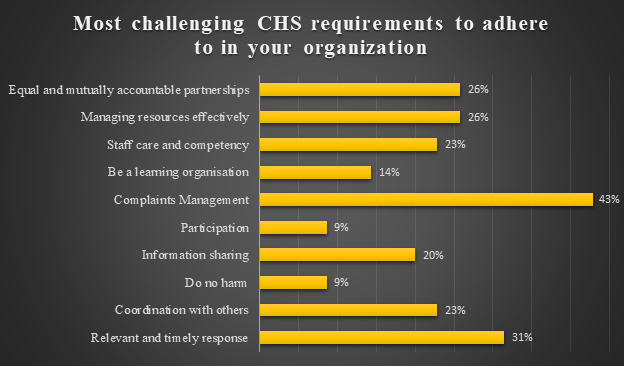

A poll was conducted asking the webinar participants to share CHS requirements that they considered most challenging to achieve.

Forty-three percent of the participants chose complain handling as the most challenging aspect to implement in an organisation. It is a common challenge to address how an organisation ensures that it has an open, accessible complaints mechanism?

Coleen shared, “At CoS, we are continuously working on making our complaint mechanism stronger. We also try to make our annual report transparent by reporting about the number of complaints we receive and types of complaints received.”

Reflections

Participants asked about ways to overcome challenges when donors are not open to receiving or reporting failures and the shift required to change this mindset.

“It is about educating the donor and not think that donors always have that back information. Sometimes it works, but other times it doesn’t. But to be vocal and to push back is vital, by doing it diplomatically and politely to make sure it happens,” advised Coleen.

There were questions raised on trust and whether organisations are doing enough to garner and sustain that trust among communities. Mayfourth addressed the question by saying,

“When we say are we doing enough, I believe its means how we are doing it together with the community. The more we involve the affected-communities in the processes, as well as project interventions, the more we are contributing to the communities. This makes them feel that they are at center of planning, implementation and assessments processes. It is very important for organisations to know for whom they are working for as this will help the project teams to feel the gaps and needs of communities which have to be catered through the interventions.”

Many of the participants also asked about how to truly embed accountability in an organisation’s core values.

“Instead of saying we are implementing the CHS commitments, we have changed this and said that these are our commitments that Act CoS signs on to. We have built them in our policies and programmes. It is also important that management be continuously questioned on whether or not the commitments are being met as an organisation. For us in Act CoS, we believe in localization and so we are working on how to make this possible in the coming five to ten years. It is about going back to the basics. When we talk about Codes of Conduct, it’s about being a decent person, when we talk about accountability, it’s about doing quality programming.”

“You journey towards accountability is not easy and time consuming, but when we see an increase in personal accountability and if there are questions raised within the organisation about these issues, then we are moving in the right direction,” concluded Uma.

[1] Hosted in collaboration by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and Community World Service Asia.

[2] Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning.

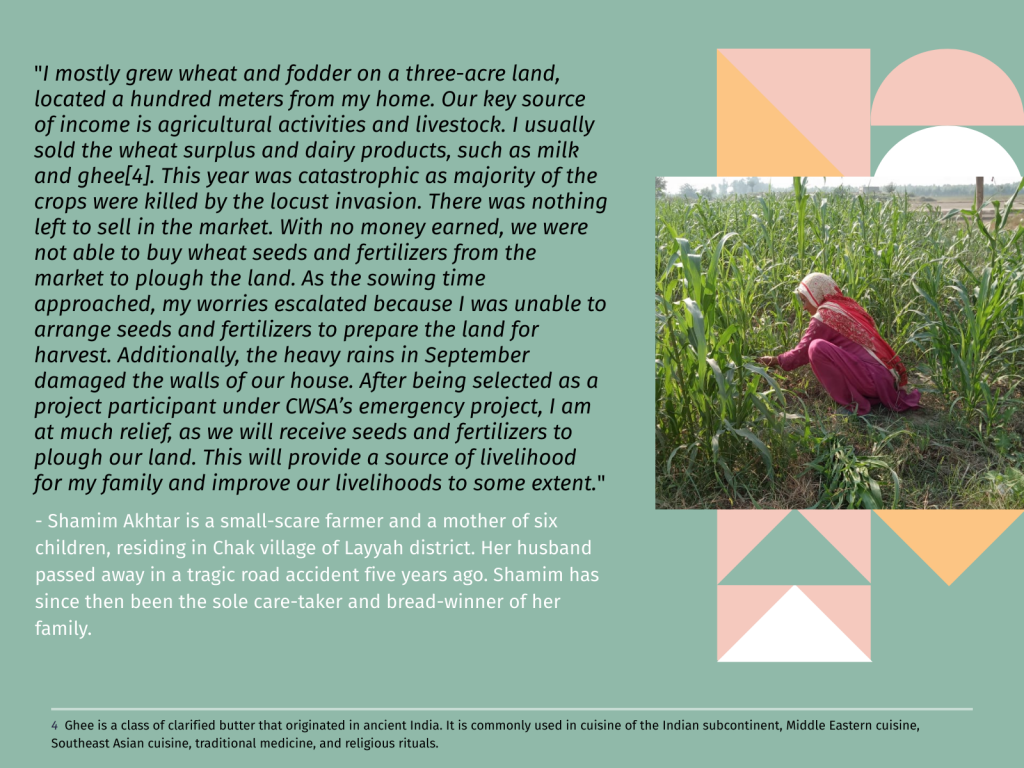

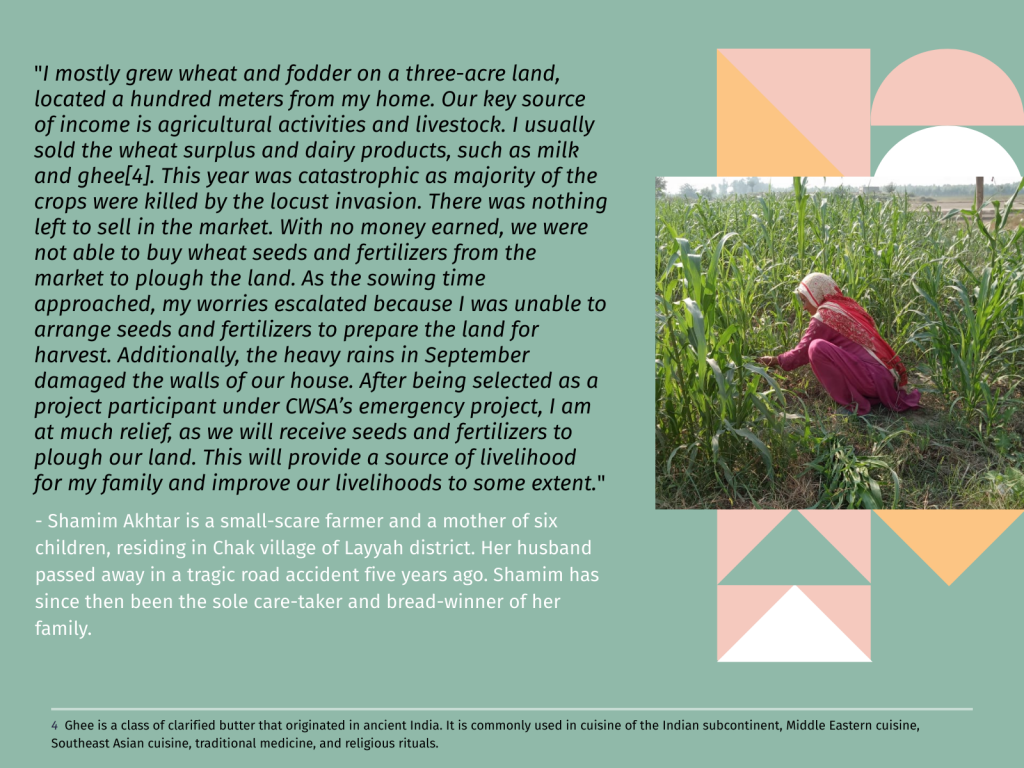

Iqbal Mai, is a widow and a single mother of three children who lives in and belongs to Bait village of Punjab province. Bait village is home to almost a hundred families who primarily depend on farming activities for a livelihood. Iqbal Mai’s children, aged between 18 and 12 years, help her with sowing, harvesting, fertilisation and irrigation activities in the agricultural fields.

Mai’s husband was also a farmer who tragically passed away after suffering a cardiac arrest in 2014.

“After the demise of my husband, I had to take all the responsibility of caring for my children and home. The tragedy that was my husband’s death however did not lessen my hopes and determination of giving a better future to my children. I started to work on the fields; ploughing the lands, sowing the seeds, irrigating the lands and harvesting the crops. I strongly believe that literacy is critical to having a chance of a better future. I see it as something that will guide my children towards a brighter future and an improved standard of living,” shared Iqbal Mai.

Fifty-seven-year-old Mai manages to send her all children to a nearby local school through the income she has been earning from agricultural farming.

Through cultivation of wheat and cotton on a two-and-a-half-acre self-owned land, Mai earns an annual income of PKR 50,000 (Approx. USD 310). Cotton is assumed as one of the main cash crops in Punjab province which is the most Agri-enriched region of the country and contributes to 22% of the country’s total agri-business. The seasonal crops cultivated in Bait are irrigated with available canal channels and the river Chenab, which is a major source of water in the region.

To prepare the land for harvest season, Iqbal Mai took a loan of PKR 30,000 (Approx. USD 186) from a well-know landlord in their village. She took the loan to prepare the land to grow wheat.

“Last year, the wheat growing on the lands was severely damaged due to wheat leaf rustⁱ. I had no other option but to take a loan to prepare the land for the next harvest season. I rented a tractor for PKR 10,000 and also paid a tube well owner PKR 10,000 to provide water. The remaining amount was consumed on labor costs for ploughing the land. Sadly, all the harvest was lost.” The recent locust invasion on the agricultural lands in South Punjab destroyed acres of agricultural land including Iqbal Mai’s little livelihood source. “We tried all the indigenous techniques to get rid of the locusts such as waving rackets on the fields and using smoke to clear out the locusts, but nothing helped. All our hard work on the field was wasted in front of our eyes. We were unable to save our harvest and had no crops to sell.”

Community World Service Asia’s Emergency response team visited Bait village for an initial assessment to select the most vulnerable and underprivileged small-scale farmers affected by the locust attacks in the area for a short-term humanitarian project[1]. Iqbal Mai was selected as a project participant. Through the project she received two bags of 50 kgs of wheat seeds each, two bags of DAP fertilizer of 50kgs each and four bags of UREA fertilizer of 50kgs each. She plough the land with wheat seeds and is actively using the fertilizers to enhance the natural fertility of the soil. Mai was also part of awareness raising, orientation and capacity enhancement sessions on learning skills and expertise about wheat cultivation techniques required to maximize yields in April and May 2020. Mai’s hopes are very high this year as she is positive to have rich and healthy crops at the end of harvest season in May 2021.

ⁱ Leaf rust, also known as brown rust, is caused by the fungus Puccinia triticina. This rust disease occurs wherever wheat, barley and other cereal crops are grown.

ⁱⁱ Livelihood Support to Small Agriculture Farmers affected by locust attack in the Punjab province project, implemented by Community World Service Asia and funded by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

Reasons for the lack of reports

Establishing trust within communities through improved communication

Identifying ways of ensuring better dialogue

These were the key discussion points at the webinar on How to Make Complaint Response Mechanism Participatory & Responsive organised and hosted by Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network’s (ADRRN) Quality and Accountability (Q&A) Hub as part of the 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events[1].

Ester Dross, expert in humanitarian accountability, facilitated the session and was joined by Janet Omogi, PSEA Coordinator at the Afghanistan Inter-Agency ( IASC).

“We have all met in the past to discuss complaints handling, so this is not something new.” A webinar on Complaints Handling was organised and hosted by Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and Act Church of Sweden in May 2020 and covered basic aspects related to complaints. However, the recent Humanitarian Accountability Report 2020 published by the CHS Alliance has again highlighted efficient complaints handling as a major gap among humanitarian organisations, with commitment 5 of the Core Humanitarian Standard being marked with the lowest scoring.

“This is worrying considering that efficient complaints handling is the key to close the accountability circle,” said Ester, initiating the discussion at the virtual event.

What are the barriers to Complaint Response Mechanism (CRM)?

Participants at the webinar shared some of the barriers people face while registering a complaint or adopting complaint response mechanisms in their organisations.

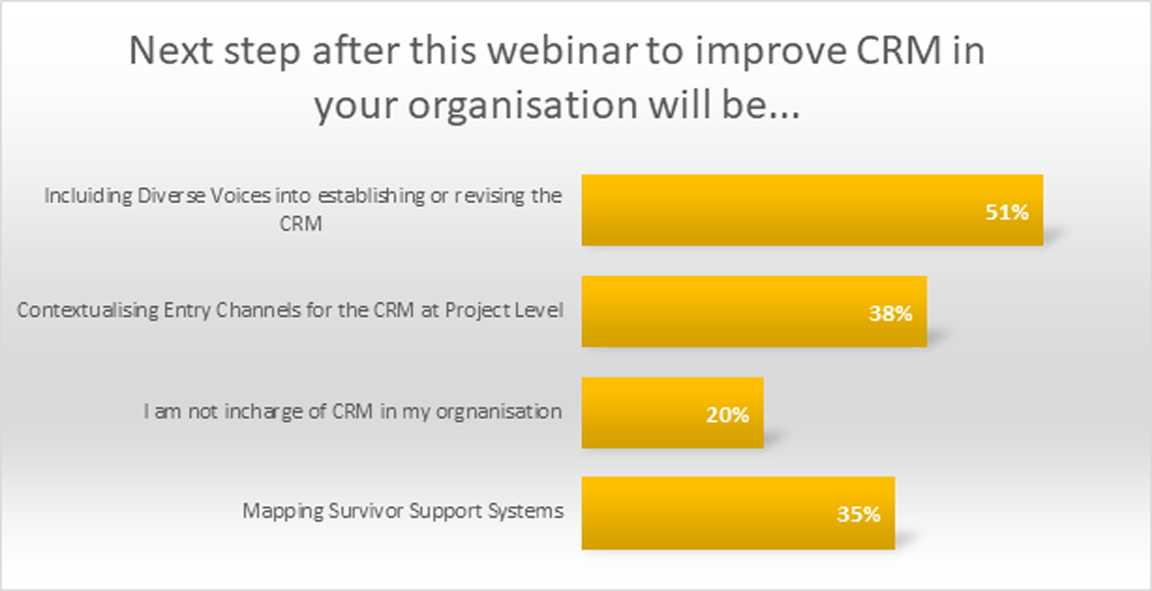

In the opening poll of the webinar, 95% of the participants confirmed that they have a complaints response mechanism in place but they also commented that the limited number of channels to receive a complaint is missing in order to make CRM effective within their organisations.

Let us move back to accountability

Accountability is based upon a number of commonly agreed commitments, interlinked with each other, resulting in an accountability circle. The key commitment within this circle is the one on receiving complaints.

“If our complaints system is not robust, how do we know if we fulfill the other CHS commitments well? Do we know if our information is appropriate, if participation is meaningful, if our staff is well-trained and well supported, if our program is efficient and timely? Our gap is the lack of efficient complaints handling; without it, we cannot be sure that we are adhering well to all the other commitments,” remarked Ester.

Giving a Voice to Communities

The IARAN report from 2018, From Voices to Choices, underlines not only the importance of community participation in decision-making and shaping projects, programs, but also contributing to processes and procedures.

“This is only possible when participation really means giving a Voice to communities which results for them to have Choices; it is therefore important to speak up and popularise accountability and a change of organisational culture.”

A quick and efficient way of giving a voice and offering choices to communities is about knowledge sharing. We need to improve and contextualise knowledge and information we share with communities. This knowledge can involve information about our projects, selection criteria, duration of the activity, staff responsibilities, staff obligations, core commitments the organisation and its staff adhere to, behavioral rules applying to staff and volunteers as well as partners, inclusiveness and diversity. Most importantly, how we encourage, receive and handle complaints. Information sharing and improved communication including around sensitive issues contribute to more effective CRM.

A short video was shared on how information can be shared on expected and prohibited behaviour to staff and the communities when technological access allows this.

“The video clearly shows that if we communicate more extensively about duties and rights, the people we work with know what to expect from us. In relation with complaints handling, this means to have more clarity on rules, simplifying the core commitments through appropriate languages and formats. It also means to have a very clear communication within communities that raising a complaint is a right and that the organisation has a duty to respond.”

Communicate Effectively and Build Trust

How can we communicate more efficiently on our complaints system?

Communicating clearly about your organisational values, missions, ethics, project activities and explaining obligations and prohibitions in a simple and culturally appropriate way in consultation with communities is key to efficiently communicating about complaints systems. It is vital to have different channels of communication for communities and other stakeholders for raising complaints: this could be through a hotline, an email, a trusted community member, and/or an external service provider.

“Communicate and demonstrate clearly that sensitive complaints will be handled outside the project or community level, that they will be forwarded to the central safeguarding unit or management and dealt with independently and professionally. Take time and be inclusive, sit together with management and staff, but also with community leaders and members to find appropriate channels and solutions to improve communications with communities and including awareness on sensitive issues and how to complain about them,” shared Ester.

Complaints boxes can seem to be an easy solution; however, a number of questions need to be addressed if they should be contributing to receiving sensitive complaints.

Building trust for all stakeholders to know that complaints are received and addressed securely and confidentially is essential. We must demonstrate that the system is accessible to all, fully inclusive and the process transparent. For building trust, it is equally important to deal with complaints in a timely manner. A robust investigation process should not last longer than thirty days. When an investigation process is over, it is important to communicate this to the complainant and survivor to inform them that the process is at its end and the findings of the investigation will soon be shared with them.

Best Practices: Addressing PSEA[1] complaints in Afghanistan

Questions were raised regarding what channels to use in remote and hard-to-reach areas and what resources to put in place to respond to complaints in conflict-affected areas?

Janet Omogi addressed the questions while talking on key strategic areas of concerns about cultural sensitivities while discussing PSEA and how they affect women in Afghanistan. She also discussed the two-way communication channels for making PSEA complaints and getting responses.

“The PSEA and CRM environment have significantly changed in Afghanistan. We see increased awareness as more agencies are involved in PSEA discussions. Most PSEA agencies have designated focal points to promote better handling of complaints. Capacity building work is improving awareness and understanding PSEA obligations. SOPs have been circulated to clusters, organisations and other response entities on how to handle PSEA allegations for better guidance. Moreover, collaborations between PSEA Task Force and Accountability to Affect Population Working Group ensures that people are better aware of their rights and of ways to report for more accountability.”

In many parts of Afghanistan, the victims of SEA are not able to speak out about abuses due to the existence of the culture of silence. The norms and attitudes about gender and hierarchy in Afghanistan does not allow the affected parties to speak openly. Additionally, the social structures in the country such as community leaders and decision makers are often men which also hinders the process to an extent. Another challenge commonly observed is underreporting. “Hiding the SEA issue under the carpet and assuming its existence, is a problem that needs to be addressed.”

Sharing some ways to address these issues, Janet said, “We continue to build relationship with all stakeholders in the country, including partner organisations, community and government officials. One of the key ways to address such issues is distribution of IEC material and building capacity. We are in the process of contextualizing and finalizing IEC material, for it to be widely used by different affect people. Moreover, we are also working on maintaining diplomatic engagement, building trust and respect, transparency and accountability with the stakeholders and communities we work with.”

What is needed for an effective complaint reporting?

To promote two-way communication channels for making complaints and getting responses that fit Afghanistan, it is important to provide a diverse range of medians for communication. This will allow the people to choose the desired channel, which makes them feel most comfortable and safe to use.

“Some community members say they are most comfortable talking to local NGOs and community leaders, whereas some prefer calling the Awaaz Afghanistan helpline[2] to make a complaint. Some organizations have internal CRMs, including phone lines and designated people, that the community can access – the more communication choices the better. We have Helpline guidelines and protocols for sharing information in the Complaint and Response Mechanism. This helps the staff on how to respond to complaints, what are the dos and don’ts and what the timeframe is to respond to a complaint.”

PSEA as a cross-cutting coordination issue

The PSEA task force cannot work alone to mitigate the issue. All agencies need to have designated PSEA focal points and alternates to enhance collective PSEA accountability. Coordination requires having the right people from different entities: the focal point list should be updated every six months. This is emphasized on because the right person is required to participate in discussions to come up with clear actions points and strategies on how best to engage further.

“In Afghanistan, PSEA is a topic of discussion in cluster, sector and other coordination body meetings, as the first agenda item, not the last. Again here, I will emphasize on the collaboration of PSEA Task Force with AAP Working Group as this helps to bring everyone on board,” said Janet.

Reflections

[1] Hosted in collaboration by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and Community World Service Asia.

[2] Protection against sexual exploitation and abuse

[3] Awaaz Afghanistan, the country’s first nationwide inter-agency humanitarian call centre, offers a single point of contact for all Afghans – including returnees and those affected by conflict and natural disasters – to receive critical information about available assistance and support, as well as to register feedback and complaints about the response.

When: 14th December, 2020

What time: 11:00AM to 12:30PM (Pakistan Standard Time)

Where: ZOOM – Link to be shared with registered participants – Register Here

Language: English

How long: 90 minutes

Who is it for: Humanitarian and development professionals, academics and UN staff committed to Quality and Accountability standards and approaches for principled actions

Format: Presentations, Group Discussion, Experience Sharing

Moderator / Facilitator: Ms. Uma Narayanan

Speakers / Panelists:

Mayfourth D. Luneta–Deputy Executive Director, Centre for Disaster Preparedness Foundation Inc (CDP)

Mr. Hiroaki HIGUCHI– Manager of Program Development Division / M&E division, Japan Platform

Ms. Coleen Heemskerk—Director of Strategic Planning, Act Church of Sweden & Board Member CHS Alliance

Background

The 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events are scheduled as a series of consultations and webinars, that will bring key humanitarian actors — local and national NGOs, INGOs, NGO networks, Red Cross and Crescent Movement, UN agencies, academics and others for focused discussions and perspective sharing on how disaster risk reduction, emergency preparedness and humanitarian response should transform in this changing context. These events are organised collaboratively by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and Community World Service Asia.

The 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events will be an online journey of three months, starting with a consultative meeting on ‘the future of humanitarian response in Asia and the Pacific’, followed by various consultations and webinars, and a research that will produce a policy paper on the sector’s future in the region.

ADRRN’s Quality and Accountability (Q&A) thematic hub is hosted by Community World Service Asia. The focus of the hub is to strengthen principled humanitarian action in the region through promoting Q&A standards, approaches and principles among ADRRN members. The Q&A hub is organising webinars and panel discussions around different themes on Q&A during the 2020 Regional Partnership Events which will result in a position paper that will advocate for continuous mainstreaming of Q&A.

About the Webinar:

Quality and Accountability mainstreaming is a strategy towards promoting and sustaining greater accountability to the affected population. For successful accountability mainstreaming to take place, changes are required at different levels in the organisation. It involves the integration of Q&A in both the programmatic and operational aspects in the organisation. Q&A mainstreaming within organisations is key to shifting attitudes and practices toward internal motivation to implement and self-monitor Q&A compliance. This organisation-wide process requires engagement across departments to assess existing practices, procedures, and policies, and then adopt changes through allocation of required resources.

Organisations tend to embark on the accountability mainstreaming process through various entry points and means. The panel discussion will explore the different levels and ways of mainstreaming accountability.

Register here: Is Accountability truly embedded in Organization’s core values and activities?

Moderator / Facilitator:

Moderator / Facilitator:

Ms. Uma Narayanan—Independent Consultant

Ms. Narayanan specialises in human resources, organisational development and accountability in the humanitarian sector. She has a background in International Organisational and Systems Development and worked as an Organisation Development and Human Resources practitioner in Southeast Asia and South Asia. She is committed to quality and accountability and is a Sphere and Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) trainer and advisor.

Photo Credit: www.unocha.org

As part of the 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events[1], a webinar titled ‘Safeguarding: Know – Act – Apply’, was hosted and organised by Asian Disaster Risk Reduction Network’s (ADRRN) Quality and Accountability (Q&A) Hub and Community World Service Asia (CWSA). The webinar discussed on-going initiatives on community safeguarding and explored how safeguarding can be adapted more widely and to traditional contexts. It also built upon approaches of familiarizing communities on safeguarding policies and the humanitarian community’s accountability to them on the issue.

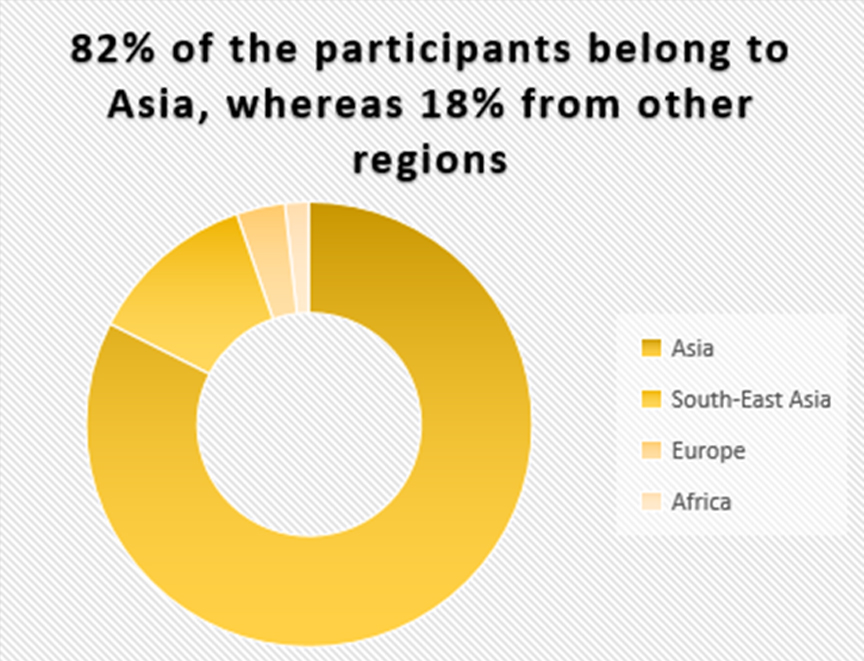

More than 250 humanitarian and development practitioners participated in this 90-minute webinar that shared a wide array of diverse expertise and knowledge from all over the world. Panelists, Smruti Patel, Founder and Co-Director of The Global Mentoring Initiatives (GMI) and Member of International Convening Committee of A4EP based in Switzerland; and Kjell Magne Heide, Complaints and Accountability Advisor at Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) based in Norway joined the session to share best practices on safeguarding.

Speaking about Protection against Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA), Ester Dross, lead facilitator and moderator of the webinar, shared, “We would like to look at safeguarding from a different angle, to give more weight to the P of Prevention. Safeguarding is a common task; a common goal and we all have a role during the travel to reach the final destination.”

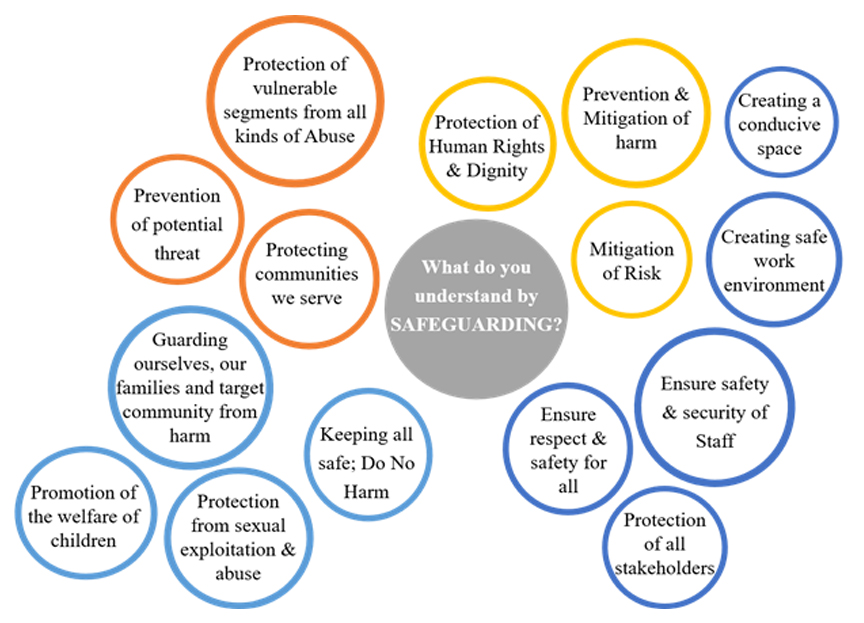

What do you understand by safeguarding? Is this a policy? Is this about protection? Participants shared their views on what safeguarding mean to them during the webinar.

Safeguarding is a framework including a range of different policies, procedures and practices to protect vulnerable populations from any harm which can be provoked by the very existence of our work, including code of conduct safeguarding policy, child safeguarding, guidelines, good practice, HR manuals, and also establishing efficient Complaint Response Mechanisms.

Ester shared, “When we talk about a safeguarding framework we speak about protecting people from any harm that we as an organization potentially bring to them – harm as a result of power imbalance, linked to gender, to poverty, to any kind of different vulnerabilities, as much for children as for adults. Internally displaced, refugees and migrants are particularly exposed to safeguarding risks.”

Power imbalances bring us to Accountability!

When talking about Safeguarding measures, it is essential to acknowledge that most sexual exploitation or abuse has as an underlying reason – the power differential between humanitarian workers and the people we work with or for. The shortest definition of accountability is the responsible use of power.

“Safeguarding and accountability is about how we change those power dynamics, how we change our organisational culture into a more open, more equilibrated, more inclusive and more diverse work space where different voices can not only be heard but lead to choices for the people who are in the center of humanitarian aid. This also means that communities need to be better integrated and taken into account when we define our safeguarding strategies,” suggested Ester.

Power is about wealth, independence, ability to set standards, influence, independence, privilege, status and but also about knowledge. It is not easy to change quickly some of these factors; however, access to information and knowledge sharing contribute to have more power, therefore sharing information and knowledge are key, not so difficult to implement and the essential basis for equilibrating power imbalances and integrate communities fully into the accountability cycle, preventing exploitation and abuse.

While sharing some of her own experiences on witnessing issues of PSEA as an aid worker, Smruti shared,

“We need to work with partners to really think about safeguarding holistically. We have to learn how to create a culture inside and outside the organisation because unless we start inside with the staff you cannot permeate that culture outside of safeguarding.”

Identifying key steps and channels to discuss Safeguarding

Smruti highlighted steps that need to be taken to ensure a culture of safeguarding through key messages. According to her, it was vital to sit together with senior management teams and initiate a discussion on value. Citing her own experience, she said,

“Through consistent and meaningful dialogue, we laid out the policies and procedures in place and staff’s knowledge on that. We mapped the communications channels in the organisation to communicate the policies and code of conduct. For instance, as part of their communication strategy, a partner organisation based in Myanmar shared how they discussed such issues during their regular staff meetings held at project level on a quarterly and monthly basis. These are opportunities to communicate the orgainsation’s code of conduct and remind people constantly on adhering to these policies at every level of the organisation.”

Secondly, building the capacity of staff on effectively bringing PSEA to the communities is essential. Since the issue is a sensitive one, it needs to be done in a strategic way for which relevant staff should be trained.

“I encouraged the staff to talk about the values as part of code of conduct in terms of transferring the code of conduct to the communities we work with. We mapped out the target communities and communication channels in place in terms of programming. We looked at those channels and what key messages can be provided through them.”

The third step is to move in the communities. This involves identifying key focal persons from among the communities to engage with on enlightening the people about safeguarding.

“In the communities we visited, there were child protection focal points, some were working on women issues as gender activists and other were working on GBV[2]. We saw these platforms as a way to communicate the key messages on safeguarding. Additionally, we aimed at setting up a mechanism through which the community can approach us with their concerns. This holistic approach ensured engagement of people on the ground, people who are dealing with safeguarding issues and get their collective wisdom, establishing the right kind of communication system in place. When the feedback came in the organisation, the key messages were drafted on basis of that. The key inspiration are those six core principles of SEA.”

Smruti encouraged organisations to explore communication networks within the communities through which key messages can be communicated and clearly understood by the communities. The key messages have to be appropriate to men, women, girls and boys. Likewise, internal messaging is as important as external messaging. Working collaboratively with other organisations is vital in addition to understanding the internal culture of the organisation.

Meaningful dialogue with communities and stakeholders helps to build trust, which is another important pillar.

“To take PSEA forward through collaborations, building trust with communities and staff through open discussions is vital. Then we ACT. By acting on the complaints and feedback, we can show the trust. To maintain trust, you need to act,” added Smruti.

Investigations as a Preventive Tool for SEA

What are the core principles of conducting PSEA investigations?

How do we encourage people for to report?

How can we overcome rumors, especially about SEA?

Participants raised these questions in the webinar. While addressing these questions, Kjell Magne Heide talked about investigations on SEA,

“You need to know the expected behavior of people that work with you and you should know how you will be able to report it. Sadly, many people do not report it. And even if they do, they have expectations which sometimes might not be realistic. Like Smruti said, there has to be a culture, it should be built into you and not rely on documents always. However, in an investigation, one has to refer to documents and policies,” initiated Kjell in his discussion about investigations on SEA.

Trust has to be earned. “It takes years to build trust and it only takes a day to lose it. You have to be structured in order to build and maintain this trust. It is therefore essential to assign a system that fits in the context you are working in and it is crucial that you follow the procedures.”

“There are some limitations to investigations, especially now in the COVID-19 situation. Be honest about the limitations with the communities, so that the people you work with have the right expectations to maintain the trust. Be sure to treat with dignity and respect. It is easy for me an as investigator to judge complaints on basis of severity. For the person who registered the complaint, it is a serious concern and therefore, I have to treat all complaints with the same dignity and respect, independent of how I as an investigator judge the severity of the case.”

Kjell recalls a case in a country office, where one staff filed a complaint of SEA against another which was thoroughly investigated and the perpetrator was found guilty and was dismissed.

“There were more complaints filed in the same context from the same office. This shows that through vigilant and transparent investigations, we can demonstrate a reaction to the alleged perpetrator when we have enough evidence. This contributes building trust with others who then feel empowered to come forward with their own concerns.”

Kjell remarked however that it is difficult to conduct SEA investigations and while investigating one has to be true to themselves and the organisation.

Key Takeaways

[1] collaborative events hosted collaboratively by Community World Service Asia (CWSA), Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA) and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA).

[2] Gender-based Violence

When: 2nd December, 2020

What time: 1:00PM to 2:30PM (Pakistan Standard Time)

Where: ZOOM – Link to be shared with registered participants – Register Here

Language: English

How long: 90 minutes

Who is it for: Humanitarian and development professionals, academics and UN staff committed to Quality and Accountability standards and approaches for principled actions

Format: Presentations, Discussion, Experience Sharing

Moderator & Presenter: Ester Dross

Background

The 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events are a series of consultations and webinars, that will bring key humanitarian actors — local and national NGOs, INGOs, NGO networks, Red Cross and Crescent Movement, UN agencies, academics and others together for focused discussions and perspective sharing on how disaster risk reduction, emergency preparedness and humanitarian response should transform in this changing context. These events are organised collaboratively by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and Community World Service Asia.

The 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events will be an online learning and exchange journey of three months, starting with a consultative meeting on ‘the future of humanitarian response in Asia and the Pacific’, followed by various consultations and webinars, and a research that will produce a policy paper on the sector’s future in the region.

ADRRN’s Quality and Accountability (Q&A) thematic hub is hosted by Community World Service Asia. The focus of the hub is to strengthen principled humanitarian action in the region through promoting Q&A standards, approaches and principles among ADRRN members. The Q&A hub is organising webinars and panel discussions around different themes on Q&A during the 2020 Regional Partnership Events which will result in a position paper that will advocate for continuous mainstreaming of Q&A.

About the Event:

Complaints handling is a key component to any safeguarding framework and remains one of the great challenges in organisational efforts to improve accountability, close the gap and listen to people’s voices. To be compliant to this commitment, we need not only to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse, but act upon received reports. For this to happen, we need to proactively facilitate reception of such complaints.

This webinar will build upon the webinar organised earlier in May this year where basic issues such as key components of establishing CRM, while taking into account increased challenges of the Covid-19 crisis were discussed. Recent public reports demonstrate once again that, even when such systems are established, reporting remains low. The How to Make Complaint Response Mechanism Participatory & Responsive webinar in December therefore seeks to explore the reasons for the lack of reports, how to establish trust within communities through improved communication and identifying ways of ensuring better dialogue.

Ester Dross—Independent Consultant

Ester Dross—Independent Consultant

Ms. Dross is an independent consultant with over 25 years of experience, specializing in accountability, prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse, gender and child protection.

Ms. Dross has had an extensive exposure to humanitarian certification systems and accountability to affected populations while working with HAP International as their Complaints Handling and Investigation Advisor, later as their Certification Manager. She has been closely involved in the Building Safer Organizations Project since 2005, dealing with sexual exploitation and abuse of beneficiaries, particularly focusing on gender and child protection. Over the last 6 years and since working as an independent consultant, Ester has been leading a pilot project for FAO on accountability and gender mainstreaming in emergencies and working with numerous NGOs including ACT Alliance members, supporting and training their staff on gender issues, child protection, accountability, complaints handling and investigations. She is an experienced investigator herself and has conducted investigations in Asia, South America, Africa and Europe.

Register here for the Webinar on Participatory and Responsive CRM

When: Monday, November 30, 2020

What time: 11:00 AM (CET)

Where: ZOOM – Register Now

Language: English

How long: 90 minutes

Who is it for: Humanitarian and development practitioners working with NGOs, INGOs, UN agencies and academic institutes

Moderator / Presenter: Smruti Patel

Format: Panellists will make a five-minute presentation that will be followed by questions and answers, providing a space for participants to ask questions.

| Background and Purpose |

The World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) in 2016 brought significant attention to Localization. The Grand Bargain confirmed a commitment from the largest humanitarian donors and aid organizations to make sure national and local partners are involved in decision-making processes in any humanitarian response, and deliver assistance in accordance with humanitarian principles. Because local actors often have the best understanding of the context and acceptance by the people in need of assistance and protection, they are essential for an effective humanitarian response. Grand Bargain states “Support and complement national coordination mechanisms where they exist and include local and national responders in international coordination mechanisms as appropriate and in keeping with humanitarian principles”.

What is the reality and experiences of local actors with the coordination mechanisms? In this dialogue, local and international actors will share their experiences and the way forward to ensure more effective and meaningful participation in coordination mechanisms.

The webinar will help to explore:

What are the shifts in attitudes and behaviors that are required?

| Webinar Speakers |

| Register her for the webinar: Coordination and Representation |