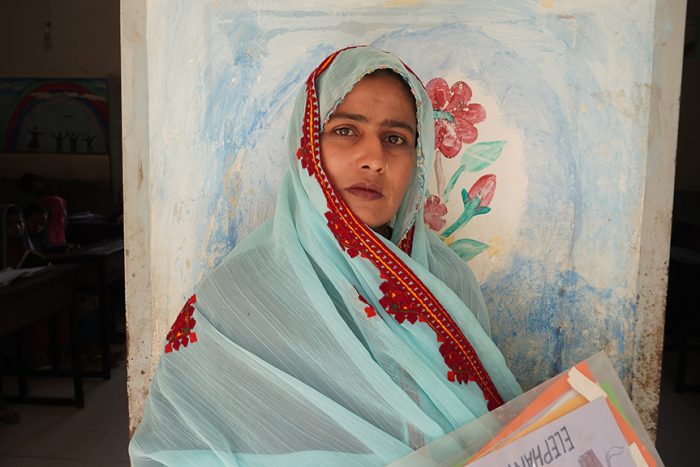

Until late 2021, then thirty-years-old Bilquis was a homemaker raising three children in the village of Sohaib Saand. Her husband works as a guard for a private school, which is approximately 5 kilometres from their home. Although a college graduate, she had been so occupied with raising her family that she believed she would never have the chance to pursue her true aspiration — becoming a school teacher. She recalls her own struggles in gaining an education, as the Saand community she belongs to continues to begrudgingly permit education for girls.

“I had to attend a school in Kunri town, and when people did not see me for a few days, they would claim I had run away from home,” says Bilquis. Fortunately, her family supported her, and she eventually completed college. Because of the challenges she had faced, she was determined to become a teacher in a girls’ school.

The lower secondary school (up to grade eight) in Sohaib Saand village was established in 1994. At that time, it offered classes only up to grade five, and even then, attendance was irregular. The dozen or so enrolled girls were rarely seen in class. Bilquis explains that mothers preferred to keep their daughters at home to help with household chores, rather than spend their limited resources on items like copybooks, pencils, and erasers. Furthermore, many parents questioned the point of educating daughters who would eventually marry and leave the family.

In 2021, with support from Act for Peace (AFP), Community World Service Asia (CWSA) hired Bilquis as a teacher at the girls’ school. Even before her official appointment, she had been urging mothers in her community to send their daughters to school. Now, with formal support, she became even more assertive in her campaign. She went door to door, reassuring parents that, in addition to the three male teachers, she was present at the school to support and protect their daughters.

Despite her efforts, challenges remained. Some mothers were so irritated by her persistence that they even threatened to physically assault her. But Bilquis’s crusading spirit was undeterred, and she refused to back down.

The initiative in District Umerkot aims to enhance access to quality, inclusive, and child-friendly education for marginalised children. The project is being implemented in close coordination with the District Education Department, Umerkot.

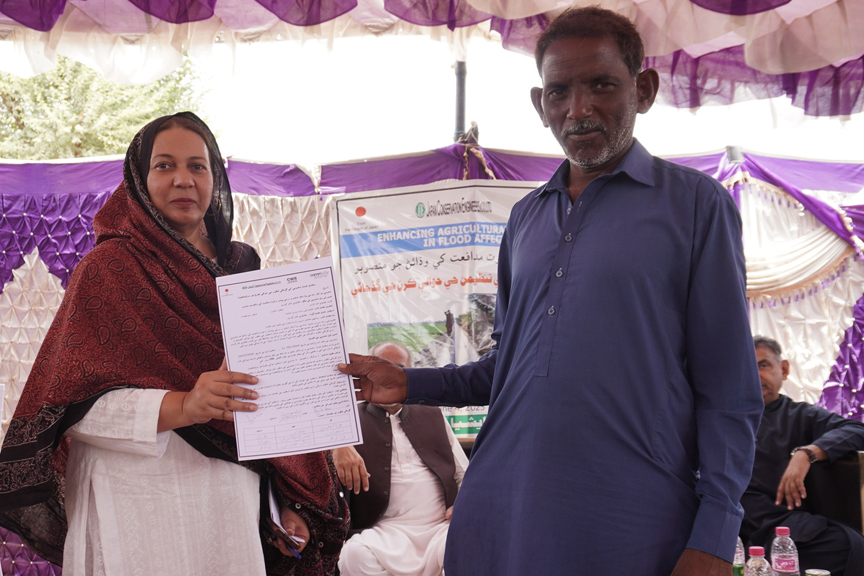

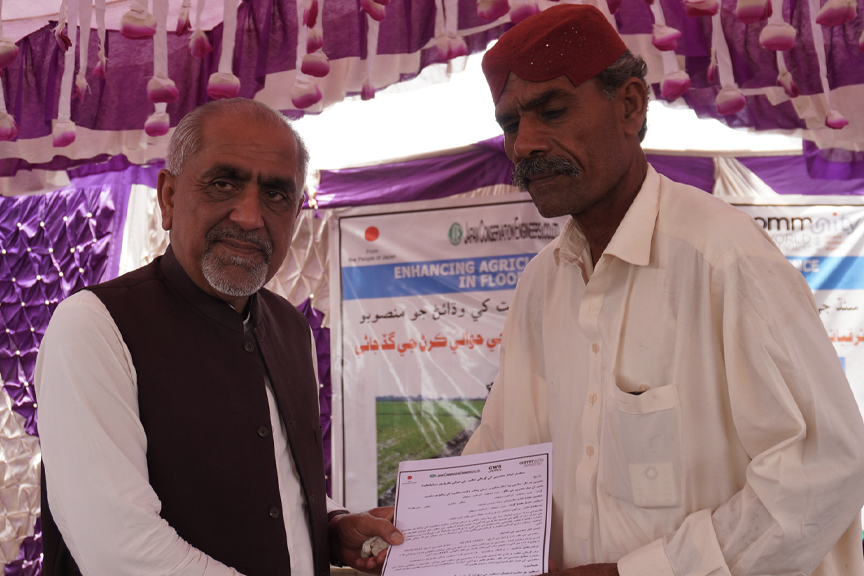

CWSA and AFP are directly supporting 4,000 students enrolled in 25 remote government primary schools located across three Union Councils — Kaplore, Sekhor, and Faqeer Abdullah. The intervention focuses on improving learning outcomes and student retention by strengthening school environments, promoting community engagement, and enhancing teacher capacity. A total of 15 locally qualified teachers — including 3 women and 12 men — have been hired to implement this initiative.

And so, from just twelve girls on the school rolls who rarely attended, Bilquis successfully managed to enrol ninety girl pupils. Of these, she reports that no fewer than seventy-five now attend regularly. With no other educated woman in the village to share the responsibility, it fell upon Bilquis to teach at both the Sohaib Saand school and the one in the neighbouring village of Haji Mian Hasan Shah. She divides her time equally between the two, spending a fortnight at each school. She proudly reports that in the latter school too — from zero — she now has ninety enrolled girl students.

The total enrolment at the schools where Bilquis teaches has reached 220 students, comprising 100 girls and 120 boys.

Bilquis recounts the story of Qamarunisa, a girl from the village of Hasan Shah, whose family forced her to discontinue her education after completing Grade Five. Being from the Syed community, they claimed that their daughters should observe seclusion upon reaching puberty. But Qamarunisa was determined to finish college and eventually join the army, inspired by the many young women she knew who were proudly serving in uniform.

Moved by the girl’s passion, Bilquis intervened. She pleaded with the family, assuring them that she would personally supervise Qamarunisa throughout her education. Her advocacy bore fruit — not only was Qamarunisa allowed to continue, but her cousin Isra was also enrolled. As of 2025, both girls are in Grade Seven and remain steadfast in their ambition to join the military.

These may be just two examples, but there are many other girls who also aspire to join the armed forces. In addition, there are those who dream of becoming teachers, doctors, and lawyers.

As the CWSA project approached its conclusion, there was a real risk that Bilquis would lose her position. Anticipating this outcome, CWSA had already formed a five-member advocacy group to ensure continuity. Comprising two women and three men — all influential and resourceful individuals — the group serves as a liaison between the NGO and government departments. Independently, the group also raises the necessary funds to pay Bilquis’s honorarium, ensuring that both her role and the education of the girls remain secure.

Both schools are now in the process of being upgraded — a direct result of the efforts of the advocacy group, which organised official visits to both institutions. The decision to upgrade was made in view of the growing number of pupils enrolled. As a result, the under-construction section of the Sohaib Saand school will expand from three to nine classrooms, while the Hasan Shah school will have a total of sixteen classrooms. This development will lead to the recruitment of additional teachers and the creation of a more conducive learning environment.

To enhance the teaching capabilities of schoolteachers, training sessions were conducted on Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE), Positive Learning Environment (PLE) strategies, and multi-grade teaching methodologies.

Bilquis shares that the training she received in ECCE, PLE, and multi-grade teaching has been immensely helpful. “My students no longer want to leave school when the day ends — and that is largely thanks to the kit (these kits include learning materials for students, such as flashcards, various alphabet puzzles, building blocks, charts, and stationery items) we received as part of the ECCE training. It makes learning so easy and enjoyable for the children,” she says.

When asked about her greatest success, Bilquis does not hesitate. Three years ago, her daughter — now in Grade Nine — had expressed a desire to transfer to a better school. However, Bilquis and her husband, who earns a modest income, simply could not afford the higher fees. Thanks to her own earnings from this programme — which provides participants with a monthly stipend of PKR 20,000 — they were finally able to make the switch.

But Bilquis considers something else even more significant: girls in the village, who previously dropped out after Grade Five, are now continuing their education.

The very mothers who once threatened to beat her now express their gratitude. They are glad they allowed their daughters to remain in school, as these girls can now read labels on products, check whether medicines are expired, and even navigate mobile phone screens — simple skills that have brought real change. Rather than making costly phone calls, mothers can now ask their daughters to send a text message, saving both time and money. These unlettered mothers feel empowered by the presence of educated daughters in their households.