Advocating for effective Complaints Response Mechanisms to ‘Close the Gap’ around Accountability

Reasons for the lack of reports

Establishing trust within communities through improved communication

Identifying ways of ensuring better dialogue

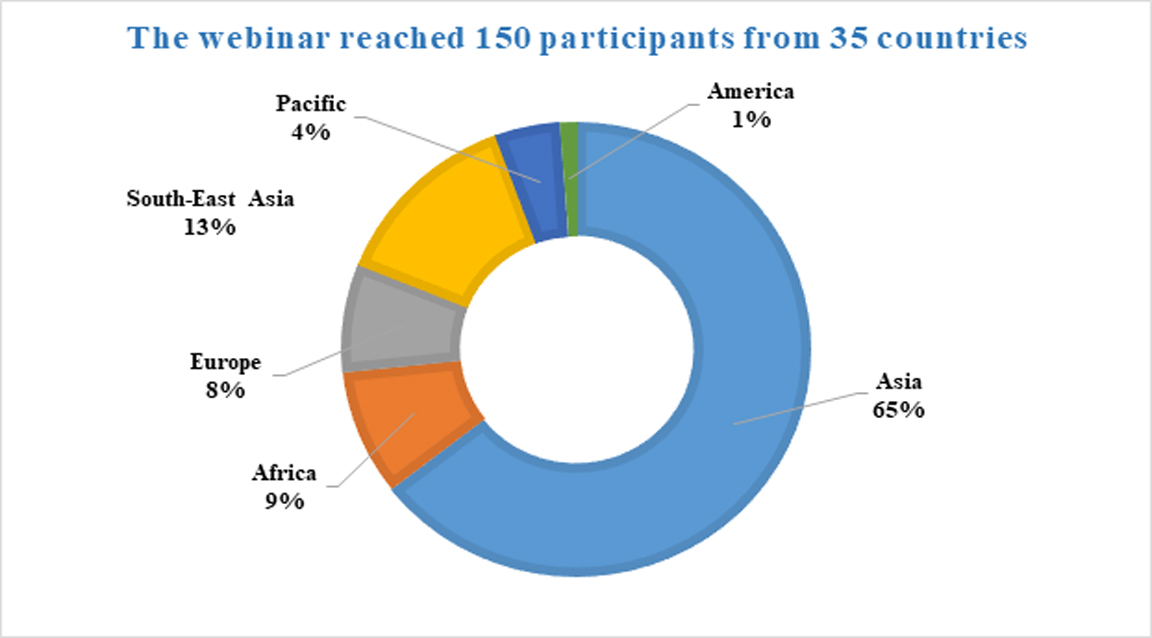

These were the key discussion points at the webinar on How to Make Complaint Response Mechanism Participatory & Responsive organised and hosted by Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network’s (ADRRN) Quality and Accountability (Q&A) Hub as part of the 2020 Regional NGO Partnership Events[1].

Ester Dross, expert in humanitarian accountability, facilitated the session and was joined by Janet Omogi, PSEA Coordinator at the Afghanistan Inter-Agency ( IASC).

“We have all met in the past to discuss complaints handling, so this is not something new.” A webinar on Complaints Handling was organised and hosted by Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and Act Church of Sweden in May 2020 and covered basic aspects related to complaints. However, the recent Humanitarian Accountability Report 2020 published by the CHS Alliance has again highlighted efficient complaints handling as a major gap among humanitarian organisations, with commitment 5 of the Core Humanitarian Standard being marked with the lowest scoring.

“This is worrying considering that efficient complaints handling is the key to close the accountability circle,” said Ester, initiating the discussion at the virtual event.

What are the barriers to Complaint Response Mechanism (CRM)?

Participants at the webinar shared some of the barriers people face while registering a complaint or adopting complaint response mechanisms in their organisations.

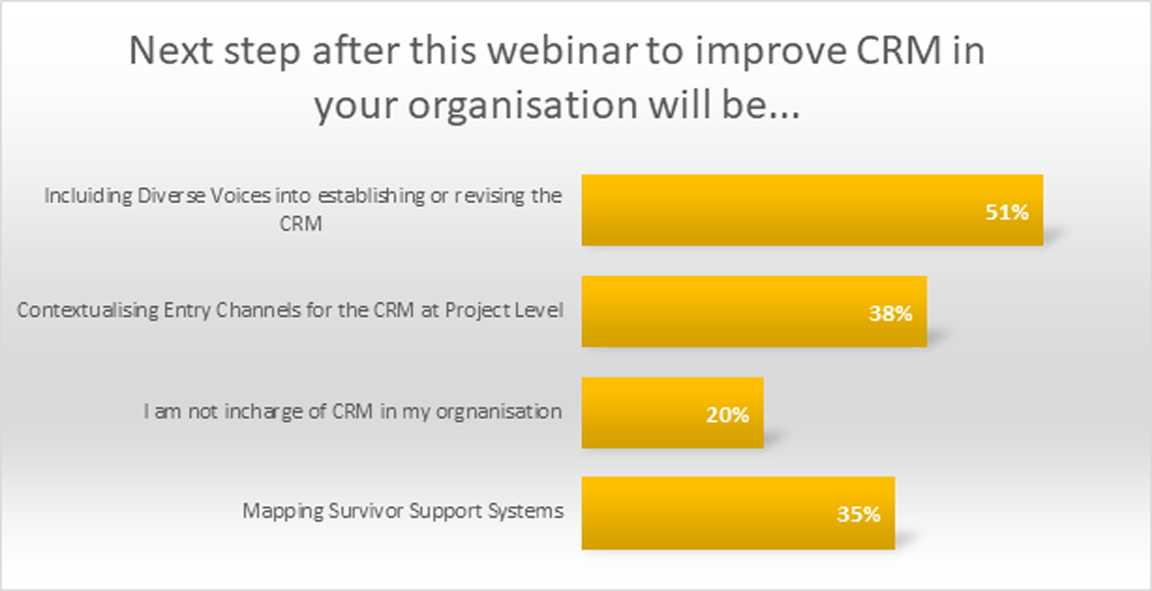

In the opening poll of the webinar, 95% of the participants confirmed that they have a complaints response mechanism in place but they also commented that the limited number of channels to receive a complaint is missing in order to make CRM effective within their organisations.

Let us move back to accountability

Accountability is based upon a number of commonly agreed commitments, interlinked with each other, resulting in an accountability circle. The key commitment within this circle is the one on receiving complaints.

“If our complaints system is not robust, how do we know if we fulfill the other CHS commitments well? Do we know if our information is appropriate, if participation is meaningful, if our staff is well-trained and well supported, if our program is efficient and timely? Our gap is the lack of efficient complaints handling; without it, we cannot be sure that we are adhering well to all the other commitments,” remarked Ester.

Giving a Voice to Communities

The IARAN report from 2018, From Voices to Choices, underlines not only the importance of community participation in decision-making and shaping projects, programs, but also contributing to processes and procedures.

“This is only possible when participation really means giving a Voice to communities which results for them to have Choices; it is therefore important to speak up and popularise accountability and a change of organisational culture.”

A quick and efficient way of giving a voice and offering choices to communities is about knowledge sharing. We need to improve and contextualise knowledge and information we share with communities. This knowledge can involve information about our projects, selection criteria, duration of the activity, staff responsibilities, staff obligations, core commitments the organisation and its staff adhere to, behavioral rules applying to staff and volunteers as well as partners, inclusiveness and diversity. Most importantly, how we encourage, receive and handle complaints. Information sharing and improved communication including around sensitive issues contribute to more effective CRM.

A short video was shared on how information can be shared on expected and prohibited behaviour to staff and the communities when technological access allows this.

“The video clearly shows that if we communicate more extensively about duties and rights, the people we work with know what to expect from us. In relation with complaints handling, this means to have more clarity on rules, simplifying the core commitments through appropriate languages and formats. It also means to have a very clear communication within communities that raising a complaint is a right and that the organisation has a duty to respond.”

Communicate Effectively and Build Trust

How can we communicate more efficiently on our complaints system?

Communicating clearly about your organisational values, missions, ethics, project activities and explaining obligations and prohibitions in a simple and culturally appropriate way in consultation with communities is key to efficiently communicating about complaints systems. It is vital to have different channels of communication for communities and other stakeholders for raising complaints: this could be through a hotline, an email, a trusted community member, and/or an external service provider.

“Communicate and demonstrate clearly that sensitive complaints will be handled outside the project or community level, that they will be forwarded to the central safeguarding unit or management and dealt with independently and professionally. Take time and be inclusive, sit together with management and staff, but also with community leaders and members to find appropriate channels and solutions to improve communications with communities and including awareness on sensitive issues and how to complain about them,” shared Ester.

Complaints boxes can seem to be an easy solution; however, a number of questions need to be addressed if they should be contributing to receiving sensitive complaints.

- What will happen once somebody drops a complaint inside the box?

- How long will it take? Who will know about the complaint?

- Who will open the box? How frequently?

- Where does it go afterwards? Who will be involved? What can one expect?

Building trust for all stakeholders to know that complaints are received and addressed securely and confidentially is essential. We must demonstrate that the system is accessible to all, fully inclusive and the process transparent. For building trust, it is equally important to deal with complaints in a timely manner. A robust investigation process should not last longer than thirty days. When an investigation process is over, it is important to communicate this to the complainant and survivor to inform them that the process is at its end and the findings of the investigation will soon be shared with them.

Best Practices: Addressing PSEA[1] complaints in Afghanistan

Questions were raised regarding what channels to use in remote and hard-to-reach areas and what resources to put in place to respond to complaints in conflict-affected areas?

Janet Omogi addressed the questions while talking on key strategic areas of concerns about cultural sensitivities while discussing PSEA and how they affect women in Afghanistan. She also discussed the two-way communication channels for making PSEA complaints and getting responses.

“The PSEA and CRM environment have significantly changed in Afghanistan. We see increased awareness as more agencies are involved in PSEA discussions. Most PSEA agencies have designated focal points to promote better handling of complaints. Capacity building work is improving awareness and understanding PSEA obligations. SOPs have been circulated to clusters, organisations and other response entities on how to handle PSEA allegations for better guidance. Moreover, collaborations between PSEA Task Force and Accountability to Affect Population Working Group ensures that people are better aware of their rights and of ways to report for more accountability.”

In many parts of Afghanistan, the victims of SEA are not able to speak out about abuses due to the existence of the culture of silence. The norms and attitudes about gender and hierarchy in Afghanistan does not allow the affected parties to speak openly. Additionally, the social structures in the country such as community leaders and decision makers are often men which also hinders the process to an extent. Another challenge commonly observed is underreporting. “Hiding the SEA issue under the carpet and assuming its existence, is a problem that needs to be addressed.”

Sharing some ways to address these issues, Janet said, “We continue to build relationship with all stakeholders in the country, including partner organisations, community and government officials. One of the key ways to address such issues is distribution of IEC material and building capacity. We are in the process of contextualizing and finalizing IEC material, for it to be widely used by different affect people. Moreover, we are also working on maintaining diplomatic engagement, building trust and respect, transparency and accountability with the stakeholders and communities we work with.”

What is needed for an effective complaint reporting?

To promote two-way communication channels for making complaints and getting responses that fit Afghanistan, it is important to provide a diverse range of medians for communication. This will allow the people to choose the desired channel, which makes them feel most comfortable and safe to use.

“Some community members say they are most comfortable talking to local NGOs and community leaders, whereas some prefer calling the Awaaz Afghanistan helpline[2] to make a complaint. Some organizations have internal CRMs, including phone lines and designated people, that the community can access – the more communication choices the better. We have Helpline guidelines and protocols for sharing information in the Complaint and Response Mechanism. This helps the staff on how to respond to complaints, what are the dos and don’ts and what the timeframe is to respond to a complaint.”

PSEA as a cross-cutting coordination issue

The PSEA task force cannot work alone to mitigate the issue. All agencies need to have designated PSEA focal points and alternates to enhance collective PSEA accountability. Coordination requires having the right people from different entities: the focal point list should be updated every six months. This is emphasized on because the right person is required to participate in discussions to come up with clear actions points and strategies on how best to engage further.

“In Afghanistan, PSEA is a topic of discussion in cluster, sector and other coordination body meetings, as the first agenda item, not the last. Again here, I will emphasize on the collaboration of PSEA Task Force with AAP Working Group as this helps to bring everyone on board,” said Janet.

Reflections

- CRM has to be able to accommodate all kind of complaints; any form of exploitation is part of sensitive complaints even if not sexual exploitation.

- Identifying and listing relevant national laws is important, as some issues should be reported to national authorities

- To encourage project participants towards reporting complaints, organisations have to build strong trust with the communities they work with

- It is essential to train staff on how to receive complaints from the field and communities directly while maintaining confidentiality and dignity of project participants

[1] Hosted in collaboration by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN), International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), UN Office for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and Community World Service Asia.

[2] Protection against sexual exploitation and abuse

[3] Awaaz Afghanistan, the country’s first nationwide inter-agency humanitarian call centre, offers a single point of contact for all Afghans – including returnees and those affected by conflict and natural disasters – to receive critical information about available assistance and support, as well as to register feedback and complaints about the response.