Overview of the Situation

Pakistan is currently experiencing intensified monsoon rainfall, consistent with forecasts from the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) and alerts issued by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). Since late June, above-normal precipitation has impacted Sindh, Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Balochistan, and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), triggering widespread flooding, landslides, and displacement.

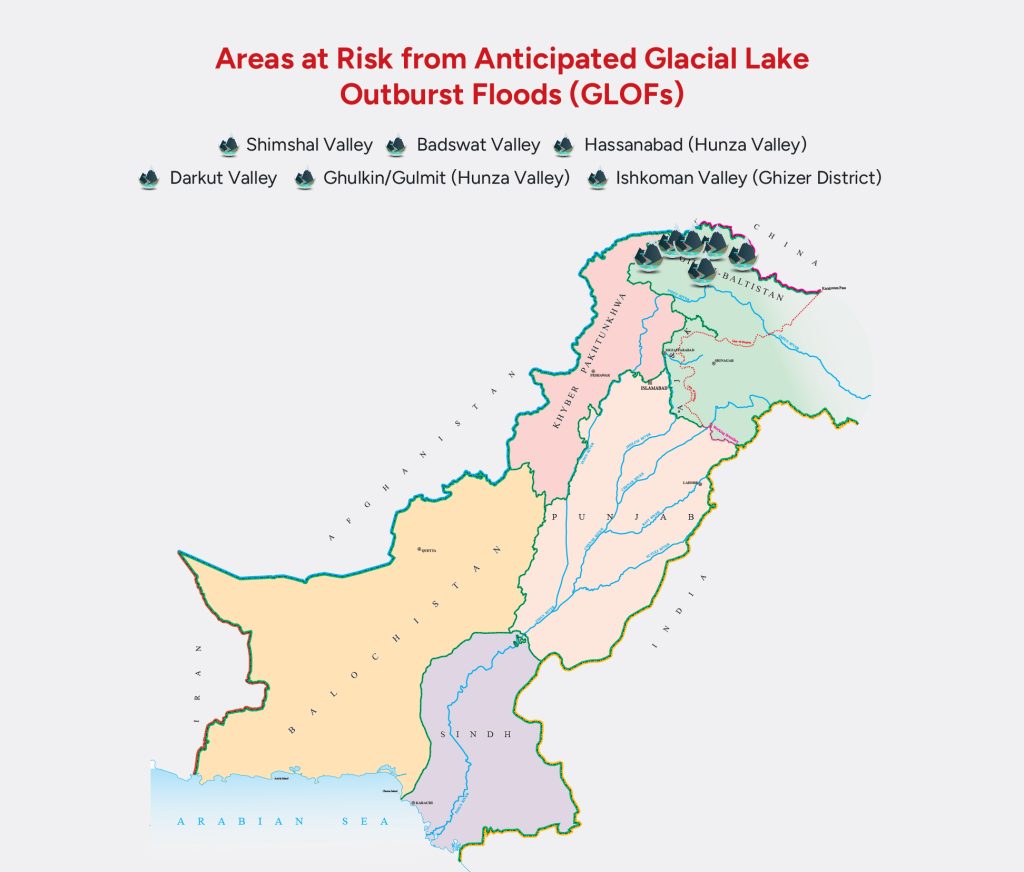

In Gilgit-Baltistan, temperatures have reached an unprecedented 48.5°C, accelerating glacial melt across the Himalayas, Hindu Kush, and Karakoram ranges. This has significantly heightened the risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), particularly in historically stable regions like Shakyote, where agricultural lands and homes have been swept away.

Sindh, in southern Pakistan, is currently experiencing a moderate to high-risk period, with urban flooding impacting major cities and a continued threat of rural flooding. While rainfall in Sindh has not been as intense as in Punjab or KPK, the province remains highly vulnerable due to poor drainage and overstretched infrastructure. Additionally, heavy rains in northern and central Pakistan can increase flood risks in Sindh through rising river levels, hill torrents, snowmelt, and GLOF events, even if Sindh itself receives only light rainfall. Local authorities have issued advisories to all relevant stakeholders to ensure preparedness.

Geographic Areas at Risk

| Province/Region | Key Areas/Districts at Risk |

| Sindh | Khairpur, Sukkur, Larkana, Dadu, Mirpurkhas, Umerkot, Badin, Thatta, Hyderabad, Karachi |

| Punjab | Rajanpur, Dera Ghazi Khan, Muzaffargarh, Layyah, Multan, Bahawalpur |

| Balochistan | Lasbela, Jhal Magsi, Khuzdar, Sibi, Naseerabad |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Swat, Chitral, Dir, Shangla, Kohistan, Mansehra, Dera Ismail Khan |

| Gilgit-Baltistan & AJK | Hunza, Ghizer, Skardu, Muzaffarabad, Bagh |

| Urban Centers | Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, Quetta |

Humanitarian Impact (as of July 16, 2025)

- 124 fatalities reported across five provinces

- 264 injuries, primarily due to collapsed structures

- 522 homes damaged, 126 livestock lost, and multiple roads and bridges destroyed

- Thousands displaced, particularly in mountainous and flood-prone zones

- Heightened vulnerability among women, children, and marginalised groups

Escalating Risks

- Urban Flooding in major cities due to poor drainage

- Flash Floods & Landslides in KPK, Punjab, GB, and Balochistan

- Rural Inundation threatening food security in Sindh and southern Punjab

- Waterborne Disease Outbreaks (cholera, malaria, dengue) due to stagnant water

- Protection Concerns for displaced women, girls, and vulnerable communities

- Recurring Disaster Zones still recovering from the 2022 super floods

Gendered & Inclusive Impact

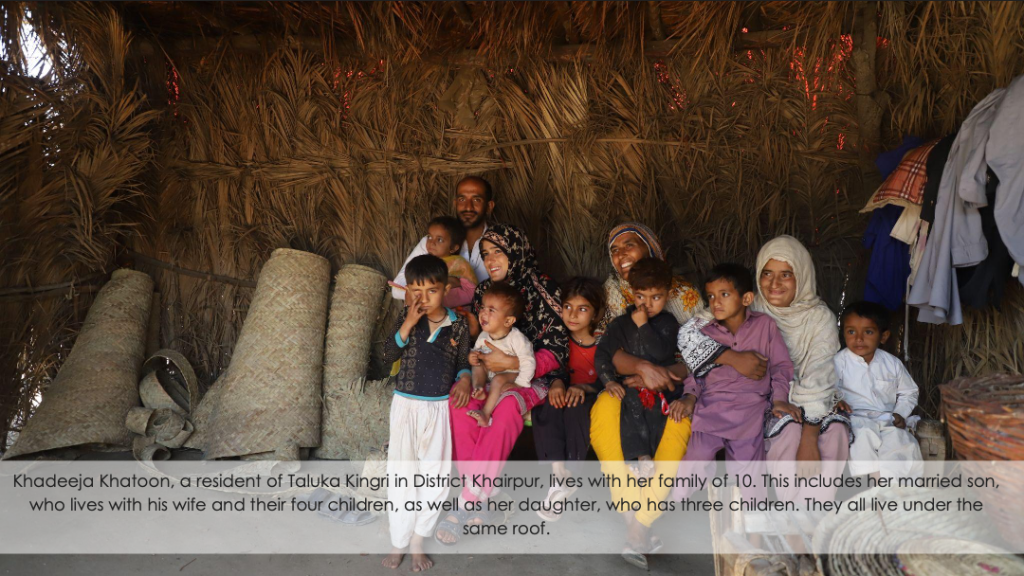

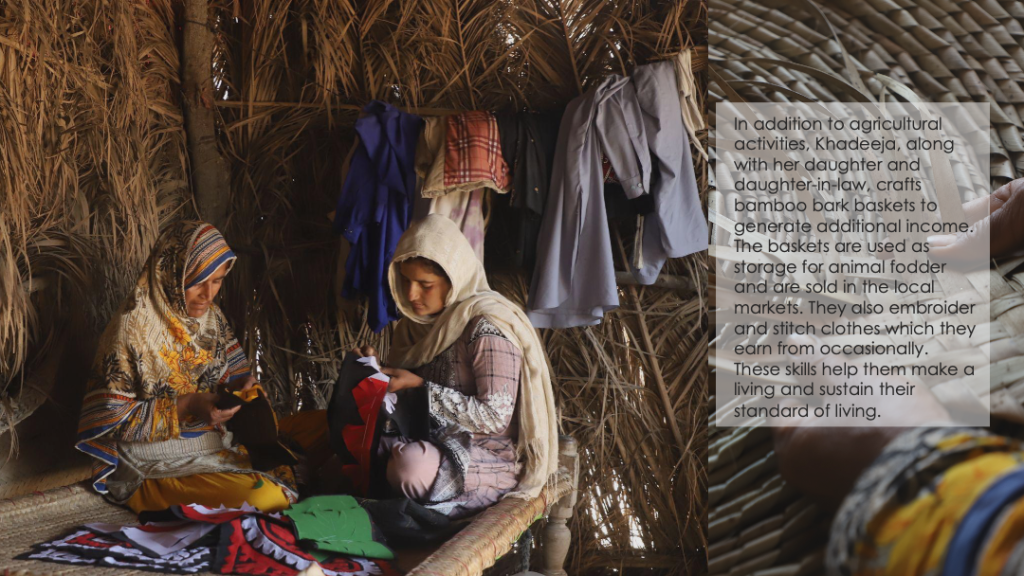

Women, girls, and marginalised groups face disproportionate risks due to pre-existing inequalities. Displacement has disrupted access to maternal healthcare, education, and safe shelter. Overcrowded conditions and lack of gender-sensitive facilities increase exposure to gender-based violence and exploitation. Persons with disabilities, the elderly, and ethnic minorities face additional barriers to accessing relief.

Anticipated Needs

- Emergency Shelter & Non-Food Items (NFIs)

- WASH support (clean water, hygiene kits, sanitation)

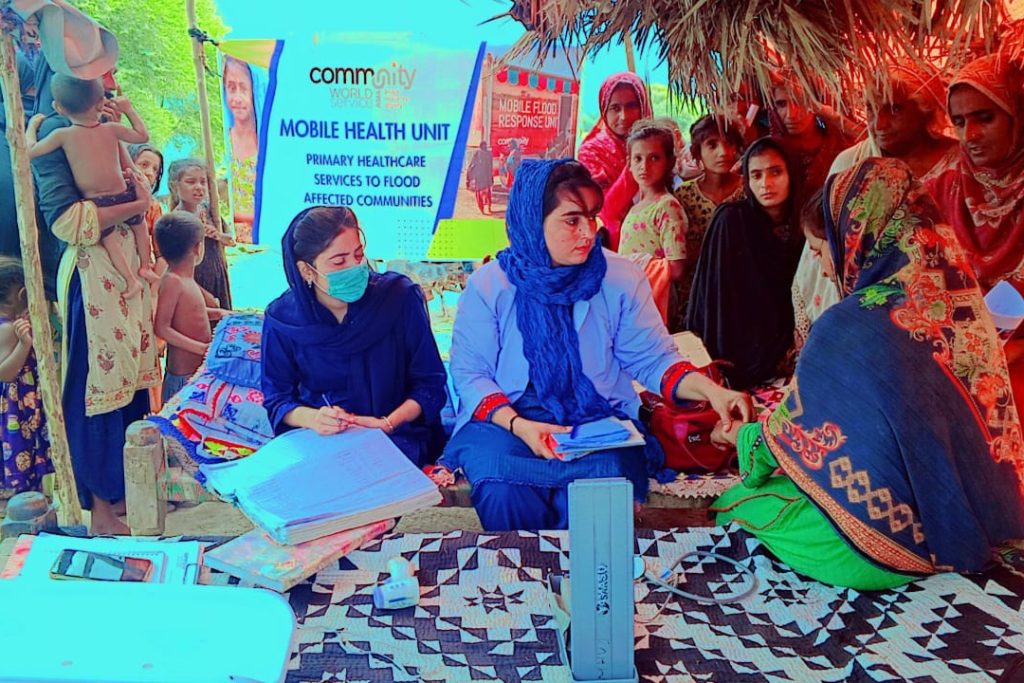

- Health services via mobile/static units

- Food assistance (cash or in-kind)

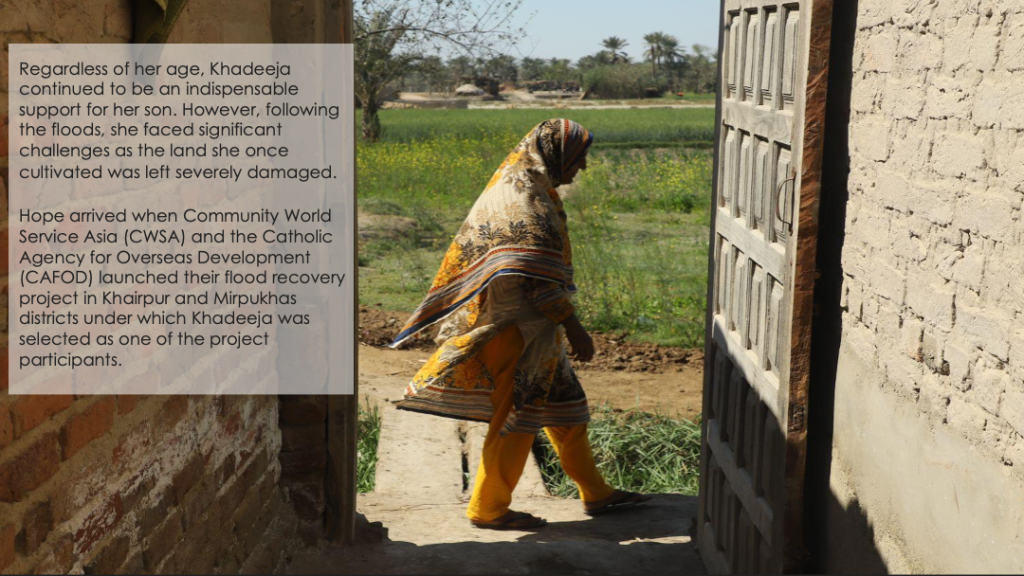

- Livelihood recovery for farmers and labourers

- Protection services for vulnerable populations

CWSA Preparedness and Response

Community World Service Asia is actively coordinating with NDMA, PDMAs, and local partners to monitor the evolving crisis. Our response prioritises:

- Gender-responsive programming across all sectors

- Mobile health units for emergency care and psychosocial support

- Protection-focused spaces for women and children

- Emergency shelter and NFIs for displaced families

- Cash-for-food assistance and in-kind distributions

- Humanitarian Quality & Accountability mechanisms to ensure dignity and community engagement

Our multidisciplinary teams are ready to deploy in active field areas, with flexibility to expand operations as needed. CWSA will initiate its emergency operations in regions where we maintain an active presence and will scale up as needed, ensuring that our response is coordinated, adaptive, and rooted in local partnerships.

Rapid Response Fund Appeal

To enable swift, life-saving assistance, CWSA is establishing a Rapid Response Fund (RRF). We call on our partners to support this fund and strengthen our collective ability to respond efficiently and equitably, within 24 hours of the emergency. Together, we can act before the storm becomes catastrophe.

The 2025 monsoon and GLOF crisis underscores the urgent need for climate-resilient, people-centered humanitarian strategies. Without inclusive and sustained efforts, future disasters will continue to deepen inequalities and reverse development gains. CWSA remains committed to protecting lives, restoring dignity, and building resilience across Pakistan’s most vulnerable communities.

Contacts:

Shama Mall

Deputy Regional Director

Programs & Organisational Development

Email: shama.mall@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Palwashay Arbab

Head of Communication

Email: palwashay.arbab@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

References

- National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) Report July 16 www.ndma.gov.pk/storage/sitreps/July2025/ilZI2GkPAVJydgrUACGH.pdf

- Social Welfare Department, Government of Sindh

- Dawn News – https://www.dawn.com/news/1920150

- PMD Report

- https://phys.org/news/2025-01-satellite-imagery-tracks-glacier-surges.html

- https://www.unicef.org/rosa/press-releases/more-1-9-children-flood-affected-areas-pakistan-suffering-severe-acute-malnutrition

- https://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Pakistan_Acute_Malnutrition_Mar2023_Jan2024_report.pdf