Mithal, a 45-year-old widow and mother to a 13 years old son, lives in Phul Jhakro village located in Thatta district, Sindh. Mithal and her son live with her mother and brother. The brother is often unwell and unable to bring home a regular income. The family is therefore faced with severe financial crises throughout the year. As a means of income, Mithal worked in the local agricultural fields picking chillies and cotton and grazed crops. The floods that hit southern Pakistan in 2010 destroyed those lands and its crops, shrinking the earnings of the family even further, forcing them to live in substandard conditions.

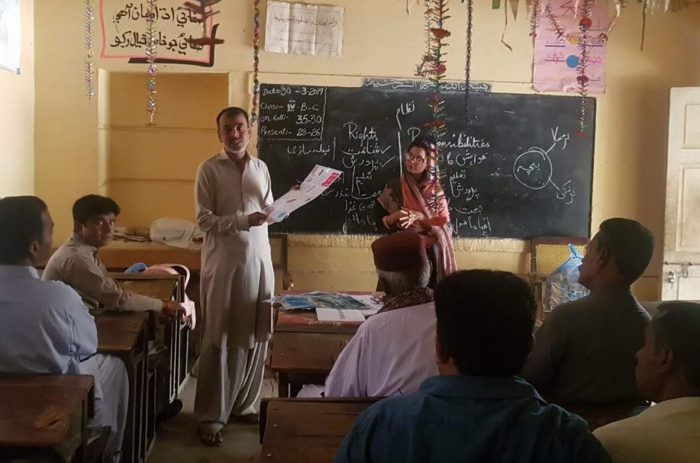

Responding to the floods, Community World Service Asia initiated relief and recovery projects in Phul Jhakro village and conducted Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Trainings in 2011.

Many villagers attended the DRR training and I was one of the participants as well. The trainings were very helpful as various exercises were conducted in order to minimize the devastating effects a disaster leaves behind. These trainings have made us more aware and prepared for any kind of disaster including fire, floods and earthquakes,

added Mithal.

Mithal proudly added that after the informative and life-saving DRR interventions, many of her fellow villagers started to become more open-minded and started welcoming new ideas and learning.

We established a school in our village in order to promote education amongst our children. The teacher belonged from our village as well. Disaster Risk Reduction Trainings are given in schools as well which has built additional knowledge and has made our children more aware in relation to disaster management.

Observing the keen interest and rapid learning of the people of Phul Jhakro, a vocational training center to develop and enhance local women artisans’ handicraft and production skills was established by Community World Service Asia and its partners. As part of the center’s program, a three-month Adult literacy class for women was conducted.

Earlier, Mithal only gave thumb impressions as her identification as she was unable to read or write. At the Adult Literacy Trainings, she learnt to read, write, and calculate basic mathematics. She also learnt to sign her name. Mithal was appointed as the monitor of her class which gave her even more confidence and motivation.

This training enhanced my educational skills, giving me the confidence to speak to other people and negotiate while taking handicraft orders.

Mithal said that many women in her village were unable to read and write as most did not go to school for basic education but with the adult literacy and vocational classes, things had changed for the better.

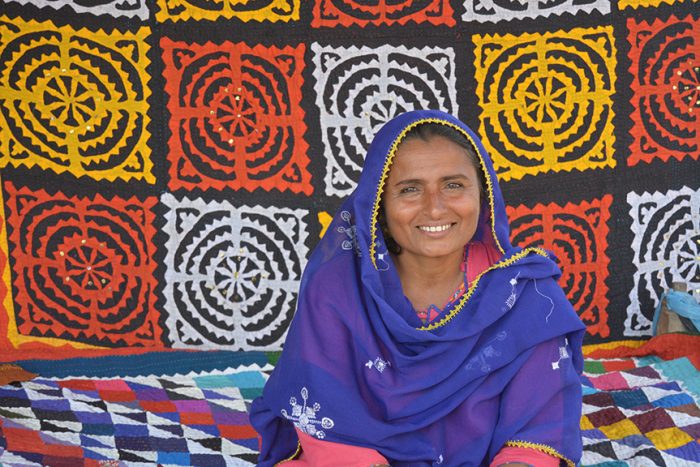

The vocational center conducted a three-month training which focused specifically on strengthening our stitching and designing skills. We were taught about family colors and how to use light and dark colors together to form vibrant designs which are both appealing and beautiful. A variety of new techniques were also taught, including appliqué work and cushion embroidery. Different stitches were practiced including Kacho Stitch, Lazy Dazy Stitch, Moti Stitch and Pakko Stitch. I enjoyed working on the cushion designs as it was new to me and I found the work to be very elegant.

Establishing and promoting the indigenous and national handicraft industry has benefits for all. Not only does it provide additional employment locally but also raises the living standards of rural communities. As part of the livelihoods and Women empowerment projects supported by Community World Service Asia and its partners, exposure visits were conducted where rural artisans met with urban buyers of Bhit Shah and Karachi. Mithal was among those who were an active part of these visits.

The exposure visits to Bhit Shah and Karachi further amplified my understanding and broadened my knowledge about the handicrafts market. In Bhit Shah, I saw block printing work on Ajraks which was completely new to me. Initially, we did embroidery on necklines of shirts only. The exposure visit to Karachi enhanced our perception and we learnt to do embroidery on shirt borders, waistcoats, bags, cushion covers and other open pieces of cloth. We now know how to keep samples of our work for future use and display for buyers.

Mithal also attended the training conducted at the campus of Textile Institute of Pakistan in Karachi, where she learnt how to make high fashion shirts, jeans and different designs of Kurtis.

The same artisans were then given orders of products to produce for a Fashion Show that would launch their handicrafts brand, Taanka, to the fashion and textile market in Lahore. Working on the production of those products was a completely different experience according to Mithal.

We made laces with various designs of embroidery, Muko and Zari work. We were not aware of what the final product, using our designs and embellishments, would look like. On my way to Lahore for the Fashion Show, I kept wondering what our pieces will be used for and how they would look and worried about the kind of response our work would get. However, when we got to the venue of the event in Lahore (the Pakistan Fashion Design Council), we saw the finished products for the first time; including sarees, shirts, kurtis, lehngas (long skirts), long coats, waistcoats, trousers, bags and scarves. We were amazed to see the complete products and how the laces and embroidery pieces were used to make such a beautiful collection. We did this, I thought to myself in disbelief!

Mithal had never in her life gotten the chance to showcase her work and talent at such a high profile event which made her even more nervous regarding peoples’ expectation and response to her work. Mithal excitedly expressed,

It was a wonderful feeling to see our work on the ramp. The zari, muko and embroidery work on the laces was immensely appreciated by the designers and guests at the event.

As Mithal shared, the women of their area have always been entirely dependent on the men in their family to go out of their homes.

This concept has changed and I now travel independently on my own. I have travelled to Karachi and Lahore. My first airplane trip to Lahore was one of the best experiences of my life. I was extremely excited to travel so far from home to promote my work further. My brother has been very supportive throughout my journey. Many villagers discouraged him not to allow me to travel on my own and promote my work. But my brother always encouraged me to move forward with my talent as I was working for a positive cause and change; for the betterment of our lives.

Mithal now receives many orders as the demand for her designing and embroidery has increased. She has received orders of various products including rillis, laces, shirts and jewellery.

My land was destroyed due to the flood of 2010. After receiving two orders of PKR 11,000, I utilized that money on replenishing the land and bought seeds to grow crops on the land again. My brother was very happy with this progress and we now grow wheat on our land which has increased our source of income further.

Mithal also now conducts DRR trainings on her own in her village to expand and strengthen women’s knowledge, empowering them in decision-making processes at times of calamity.

The villagers address me as an officer as I have travelled to Lahore and Karachi to progress my hard-work. Even my son calls me a professional officer and proudly walks in the streets of our village.

Most women in the village are more encouraged now as they see Mithal’s example, by stepping out in the world to play a better role in the socio-economic development in her respective community.