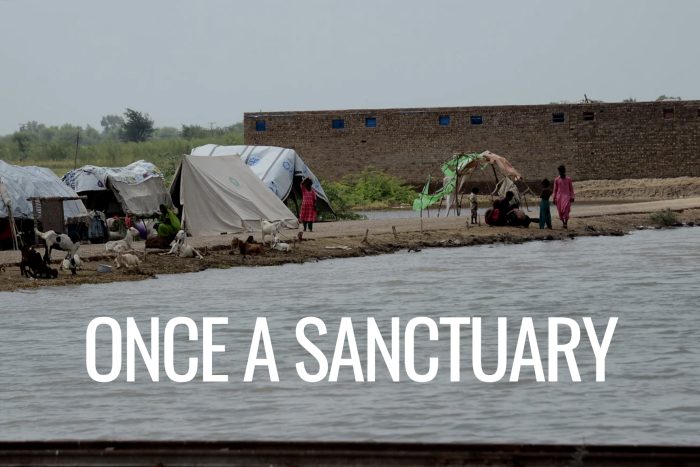

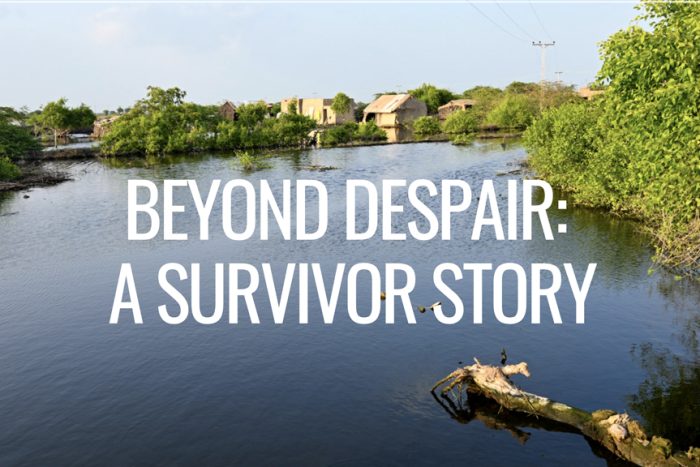

Village Dharshi Bhagat lies by the road connecting Samaro town with Samaro Road; the latter being the town’s railhead where the old abandoned metre-gauge railway station still stands for the first two weeks after it started in late July, the rain did not stop for a minute. Thereafter it continued to teem down with brief intervals lasting never more than some minutes until the village went under a metre of water.

Twenty-five-year-old Heeru was only days from delivering her baby when it started. As the water rose, she and some other women made a desperate run to save whatever little cotton they could from the fast drowning field they had so carefully tended the land they worked as labourers. The struggle in mud and water was worth only a few thousand rupees.

With the village going under water, she and her family left their home and the fields and moved to the only stretch of road that was above the dark water. For three months, they lived under a makeshift shelter of bamboo poles holding up plastic sheeting for a roof. It was good fortune that Heeru had salvaged some cotton and there was some cash for food because in the time of the rising waters, she gave birth to her second child, a daughter. When her pains began, her husband hired a motorcycle and ferried Heeru to the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road where she fortunately got the attention of the doctor and a safe delivery.

Not long after the birth of the child the meagre cash in her kitty ran out and her family subsisted on chilli paste and roti. Their one goat provided a small amount of milk daily. It was a hard life for the family, especially so for the young lactating mother.

Heeru recounted how her firstborn, a son, had died two years ago aged just four months. The child had gone down with fever and convulsions and though the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road was just 4 km away, the parents were tardy in taking him there. For five days the poor child suffered and when they eventually did get to the BHU, the doctor could do nothing to save the baby.

For some inexplicable reason, seeking medical assistance was simply not a priority for these poor people. They still relied on folk medicine and even considered milk tea some sort of panacea.

Dharshi Bhagat, who gives his name to the village, said Heeru’s husband was lucky to be able to rent a motorcycle because shortly after, the only transport capable of plying on the submerged roads were big four-wheel drive vehicles. An ailing person had to be carried either on a string bed or piggyback all the way to the units either in Samaro or Samaro Road. And this was a time of rampant disease. Fever, skin infections and diarrhoea were raging in the makeshift camp strung out along the road. In that desperate time of zero income, men were seen carrying the ailing to the BHU.

In mid-October, the first Community World Service Asia’s medical mobile unit reached this village. The village was still submerged and the mobile unit had to be parked on the road, the only strip of land free of water. Dharshi Bhagat said this came not a day too soon for who would not have appreciated this gratis service at the doorstep in that time of great adversity.

Lady Health Visitor Farkhanda said the mobile unit had been on the road for ten weeks moving from village to village and treated on average a hundred and fifty patients every day. On the first visit to Dharshi Bhagat, they had a similar number between nine in the morning and three in the afternoon. Referrals of more complicated cases was made to the Samaro town hospital. Common complaints were malaria, water-borne gastro-intestinal, eye and skin infections. This time around, respiratory tract infections had increased and the demand was for ‘pills for strength’, as multivitamin tablets are referred to.

Outside, among the crowd of men waiting to consult the doctor Bhoomo said he felt weak and his ‘liver burned’ and showed a handful of blister-packed multivitamin tablets and an antacid.

“The first time the medical van visited our village, I was suffering from the same, but I had been out cutting mesquite to sell in neighbouring villages and I missed my chance to see the doctor,” said Bhoomo. For him his suffering was secondary. Most essential was for him to make some little cash for food.

Why hadn’t Bhoomo gone to the hospital in town during all this time? “I have no money, the fare out and back is Rs 40, and after I spend a day cutting mesquite, there is only enough cash to purchase food for my family of nine. I cannot afford to go to town.”

On the second visit in mid-November the mobile health unit had in just two hours treated one hundred and thirty patients. And an equal number waited patiently outside. Some like Dheero said they had no complaint and had come only to watch the goings on; most others complained of stomach ache and fever. Nearly all of them had either simply suffered stoically or experimented with folk medication to no effect. The lament was the same all around: they had no money to visit the hospital in town. And they could not afford to take time off from their struggle to earn some money.

Listening to the very vocal Kasturi, suffering in silence seemed to come naturally to them. She had a reasonable income from working as a seamstress while her husband was a door-to-door clothier. Their once comfortable life was now reduced straitened circumstances.

“The crops have all been destroyed. There is no work and therefore no money. Who can order new clothing in these times? The Lord is kind, I took great precautions and my three children did not fall ill, but families with illness could either feed themselves one, or at most two, meals a day. They did not have the means to make frequent trips to the Samaro hospital.”

Dharshi Bhagat was right: the mobile unit had come not a day too soon.