Local and national non-profit organisations and Disaster Management Authorities (DMAs) are most often the first responders to a disaster, besides communities themselves. While being at the forefront and equipped with rich indigenous knowledge and experience, they face a multitude of challenges while responding to multiple crises due to institutional and staff capacity constraints. “Local organisations are often focused on their project work and have limited resources. The knowledge and opportunities to mainstream accountability in their working mechanisms is limited and complying with all international standards becomes difficult. Therefore, there was a need for formal capacity building of local organisations and disaster management authorities, on quality response and accountability to affected people” says Aamir Malik, Director RAPID Fund, Concern Worldwide.

As a Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) Alliance member and Sphere regional partner and focal point, Community World Service Asia partnered with Concern Worldwide (CWW) to augment the skills and competencies of Concern’s staff, their partner organisations and DMAs, on Quality and Accountability to Affected Populations (Q&AAP) through a series of workshops. “Concern assessed institutional needs for training and identified gaps between project interventions and the application of Quality & Accountability standards. Concern collaborated with Community World Service Asia, who already have substantial expertise in the field of mainstreaming Q&A, Sphere, and Core Humanitarian Standard in humanitarian action,” shared Ishtiaq Sadiq from Concern Worldwide.

After an MoU was signed between the two organisations in 2019, a thorough consultative process between the two parties took place. Multiple meetings were arranged to discuss and finalise course outlines of Q&AAP trainings; complete workshop materials were developed and finalised as per CWW feedback. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, the trainings transitioned into a virtual model. Since the start of the collaboration, eight workshops have been conducted for 187 participants representing 87 different partner organisations from Sindh and Balochistan as well as PDMA Sindh. These workshops aimed to raise awareness on key standards such as Sphere and the CHS that support organisations with effectively mainstreaming and implementing quality and accountability through a people-centred approach. Through the learning series, participants were enabled to outline opportunities and challenges in implementing Q&AAP, and were provided a platform for experience sharing and peer learning on its practical implementation

Participants strengthened their skills on Q&A standards and commitments and learned to apply them according to their contexts. They also designed a Q&AAP learning action plan tailored to their specific needs and identified ways of collaborating and coordinating with other partners to improve Q&AAP in a response. “We not only designed a training workshop for the participating organisations, but we provided technical support in mainstreaming the standards in the organisation systems and policies,” shared Aamir.

Concern’s Rapid Fund collaborated with CWSA on its Q&A interventions and jointly developed a plan for its implementation. CWSA conducted the Q&A focused trainings for them with the facilitation of the Rapid Fund team.

Lessons Learned; Improving Accountability Together

A virtual meeting was held in June 2022 to draw conclusions on the workshops’ successes and failures to improve content and resources for future workshops. During the meeting, the objectives and methodology of the workshop were shared, the draft content was presented and analysed and results and challenges thoroughly discussed. By the end of the meeting, recommendations for future learning events were brainstormed and shared.

Participants’ Selection, Self-Assessment and Pre-Training Coordination

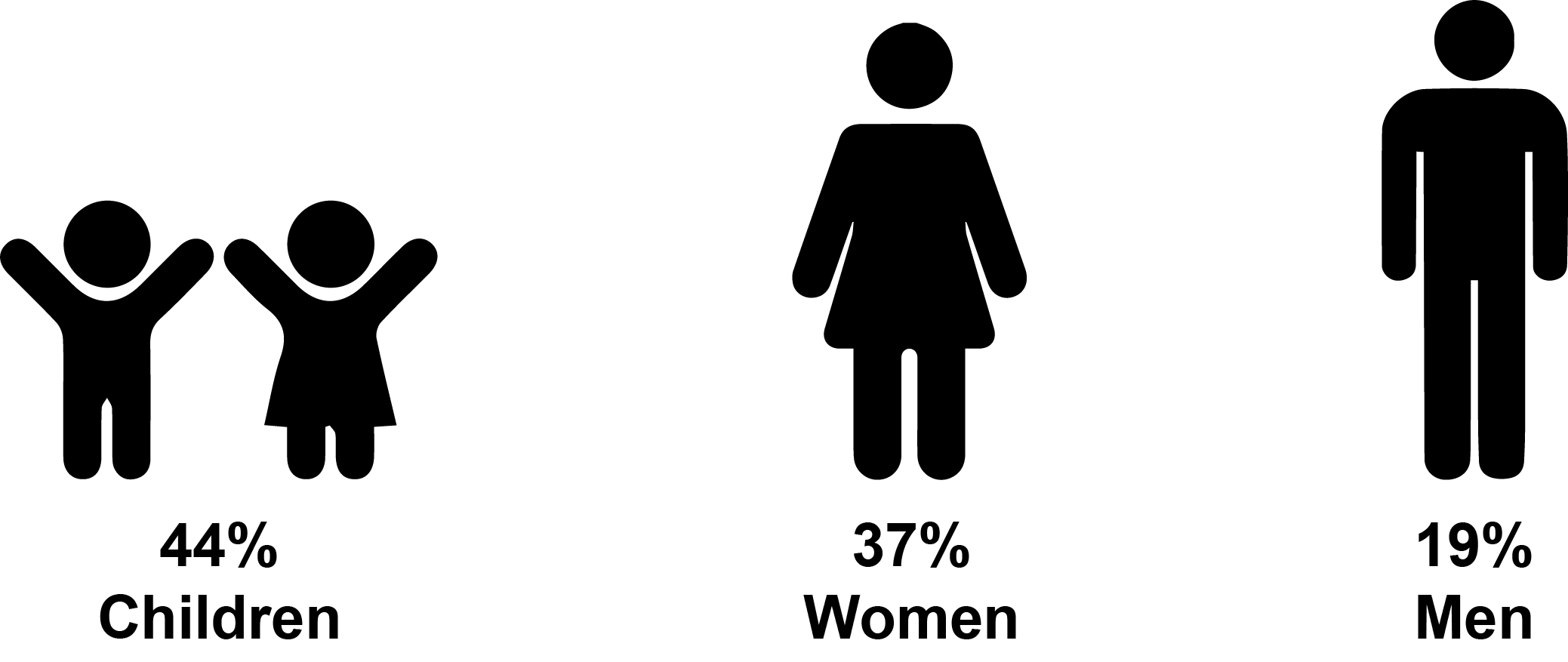

Gender balance was ensured during participants’ selection which was done based on relevance and experience of the training topic allowing richer, more contextualised discussions and peer learnings.

Self-assessment done by each participating organisation to evaluate its structure, policies and procedures was an effective tool to gauge organisational standing on Q&AAP and identify improvement areas. This led to effective development of training plans and agenda based on participants’ needs and expectations.

Resources such as Sphere handbooks shared prior to the training were useful, allowing participants to review them and come prepared with some knowledge of the topics to be discussed. WhatsApp groups were created for participants, which allowed peer learning and continuous coordination.

Workshop Assessment

Appropriate time allocation and pace, and recap of learnings from the previous day played a key role in keeping participants engaged throughout the workshop and ensured consistent productivity during the sessions. The workshops were conducted online for which orientation on Zoom was given to participants in addition to provision of internet devices to prevent technical glitches. The training was made interactive and engaging through open discussions, breakout rooms and utilization of Google Jamboard. Comprehensive sessions on Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) increased awareness of most organisations. Case studies for Q&AAP guidelines were shared from the Asia Pacific region such as a CRM developed by World Vision in Sri Lanka, giving participants contextualised and local examples from the region.

Pre- training resource sharing proved to be effective and were used post-training by participants to refer to guidelines, standards and other tool kits. The pre and post tests were easy to take/complete.

Institutional Capacity Strengthening

Upon training completion of each module, a technical assistance phase was launched within a couple of months that offered coaching and mentoring support to organisations in developing and updating Q&AAP related guidelines, namely a Code of Conduct (COC) and Complaint Response Mechanism (CRM). CWSA provided inputs and guidance through sharing of templates, sample documents and key notes to participating organisations throughout the process; their progress was regularly monitored until final submissions were made by each of them.

Updated policies of organisations were appreciated by networks and funding partners. It also paved way for more effective implementation of Q&A tools and techniques in organisational processes and policies.

The ARTS Foundation did not have a CRM prior to the workshop; they utilised the draft shared with participants during the technical assistance phase to develop one from scratch. SHIFA developed specialised policies on each topic as the organisation had a joint policy before the workshop. Community Development Foundation (CDF) developed its COC and CRM policies which provided them a pathway to apply for CHS Alliance membership.

Key Learnings & Takeaways:

“The participating organisations are now more familiar with globally recognised Quality & Accountability initiatives including Sphere, Humanitarian Standard Partnership (HSP) and Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS). Organisations have also mainstreamed CHS and the Sphere handbook in their newly developed or revised policies and guidelines on CoC and CRMs for improved accountability towards the communities they are serving.” Speaker/Technical Expert on Q&A

“Nari Development Organisation (NDO) has established a CRM and placed complaint boxes within the office and the communities we are working in. We are also conducting orientation sessions with the NDO staff and communities regarding the new CRM policy and its processes. This initiative has mainstreamed accountability towards the communities and staff we work with and ensures a people-centred approach.” Zahid Hussain, Nari Development Organisation (NDO)

“Every action has to be guided by the common belief in the equality of all people, the inviolability of their rights and the right of each individual to self-determination. In the spirit of solidarity and humanity, the goal of every organisation is to improve the lives of people in the places where they can work. This workshop provided guiding tools, such as CoC and CRM, which allowed us to mainstream accountability in all the work we do. We updated our existing policies and adhered to the CHS and Sphere standards to better respond and allow community voices to be heard.” Liza Khan, Community Development Foundation (CDF)

“The extensive feedback we received on our existing CoC and CRM allowed us to mainstream CHS and Sphere Standards in our revised policies. Moreover, we receive all kinds of complaints. Some are relevant to our work and some do not relate to our work. There have been instances when we have received fake complaints as well. Organisations should be able to differentiate between these complaints and address them equally and in a transparent manner.” Gulab Rai, Sukaar Foundation