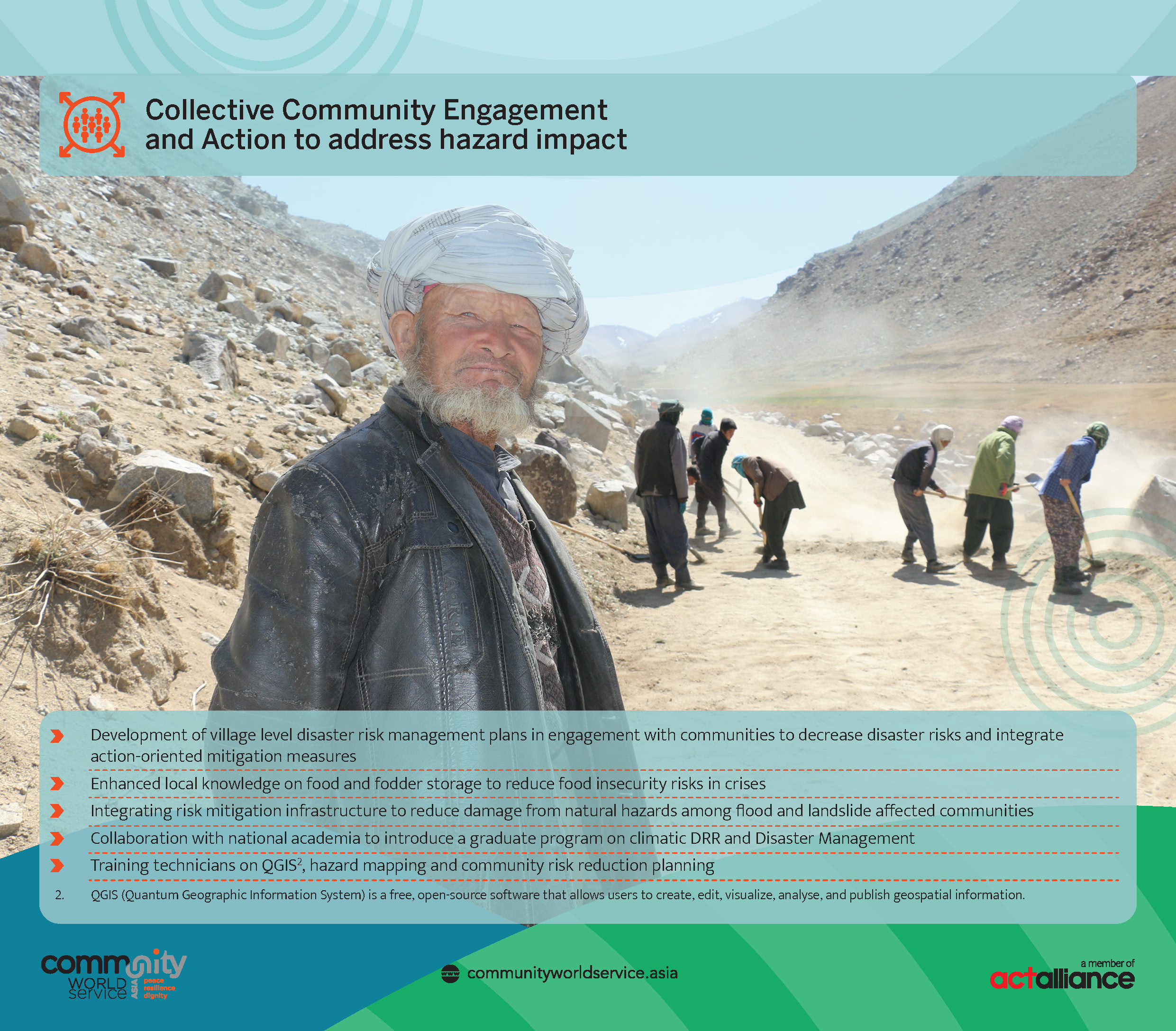

On this International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction, Community World Service Asia underscores its commitment to addressing the linkages between disasters and inequality. With continuous community engagement and the support of our partners, CWSA integrates Climate Action and Risk Reduction into its programming as well as into its organisational development. As we operate in a country (ies) that is at high risk of disasters and is among those with the highest share of the population living under the poverty line, we design projects, engage with communities and help develop long-term community structures that prevent and reduce losses in lives, livelihoods, economies and basic infrastructure caused by disasters.

Yearly Archives: 2023

Training on: Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management

When: 16th-18th October, 2023

Where: Peshawar, KPK

Language: Urdu & English

Interested Applicants Click Here to Register

Last Date to Apply: 20th September, 2023

Rationale:

In an era defined by dynamic shifts in development and humanitarian approaches, the essence of community engagement has taken on global significance, both upstream and downstream. This evolution has reshaped how we conceptualize, plan, and gauge impact within the ever-changing world ecosystem.

The “Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management Training” emerges as the compass guiding professionals through the intricacies of modern impact assessment, along the project plan. By unearthing advanced methodologies, pragmatic frameworks, and illuminating case studies, this training empowers participants not only to measure impact but also to strategically align interventions for comprehensive community advancement objectives.

Training Objectives and Contents

This program is about navigating the entire project lifecycle with finesse. From meticulously crafting program design to seamless implementation, rigorous monitoring, and impactful assessment, we encompass ensuring that projected outcomes become documented realities.

By joining this training, the impact of your interventions becomes your ally, from inception. Discover how to harness cutting-edge data collection and analysis tools that empower your impact measurement. Our training doesn’t just stop at knowledge – it’s a bridge to practicality. Real-world exercises, tailored to the times with social distancing in mind, weave seamlessly with expert lectures and the invaluable exercises for experience sharing by eminent leaders in the development and humanitarian sector. With post-training coaching and mentoring bolstering 30% of participant organizations, your growth is our relentless pursuit. Dive into the heart of impact management as we delve into:

- Mastering program design with an impact and learning lens

- Commanding Theory of Change/Change Models for dynamic interventions

- Immersing in a spectrum of impact measurement and evaluation tools, from data and tech powered analysis solutions to remote data collection innovations

- Fusing Quality and Accountability standards with humanitarian programs, forging a path of excellence

- Pioneering peer support action plans and nurturing coaching/mentoring avenues

Number of Participants

We encourage you to join an exclusive group of 20 change-makers, by accepting applications from diverse backgrounds, including women, differently abled individuals, and aid workers from ethnic/religious minorities. Priority is given to those from under-served areas. Deadline to Apply is by September 20, 2023.

Selection Criteria

- Primary responsibility for monitoring and impact assessment /MEAL staff at the project

- and/or organizational levels

- No previous exposure/participation in trainings on Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Measurement

- Mid or senior level manager in a civil society organization, preferably field staff of large CSOs or CSOs with main office in small towns and cities

- Participants from women led organizations, different abled persons, religious/ethnic minorities will be given priority

- Willing to pay a fee PKR 20,000 for the training. Exemptions may be applied to CSOs with limited funding and those belonging to marginalized groups. Discount of 10% on early registration by 10 September, 2023 and 20% discount will be awarded to women participants

Facilitating Agency

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) is a humanitarian and development sector organization, registered in Pakistan, head‐quartered in Karachi and implementing initiatives throughout Asia. CWS/A is a member of the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) Alliance, a member of SPHERE and their regional partner in Asia and also manages the ADRRN Quality & Accountability Hub in Asia.

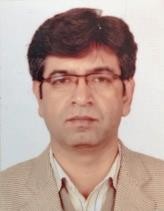

Facilitator/Lead Trainer: Mr. Mohammad Tayyab

Mohammad Tayyab specializes in planning and accountability measures of projects and programs within the development and humanitarian sectors. With over 20 years experience of working for development sector projects, programmes and institutions, and a strong background in designing and conducting social research and MEAL assignments, he has successfully contributed to the sector in Pakistan and in other countries. He has evaluated the impacts of programs, synthesizing lessons learned, and fostering a knowledge management culture to empower institutions.

One of Mohammad’s key strengths within the MEAL processes is his ability to effectively engage with diverse stakeholders, both individually and in group /institutional settings. His work has also played a pivotal role in facilitating organizational development for a wide range of international and national NGOs, bilateral and multilateral organizations, as well as corporate companies. In addition to his project and program planning expertise, Mohammad has conducted extensive research in social and institutional aspects. His research encompasses a broad spectrum, including public sector institutions, corporate companies, and social organizations. Within his area of expertise, which includes climate change, livelihood, gender, DRR and humanitarian response, he has particularly excelled in enhancing institutional and program effectiveness within these domains.

Lets Not Shift the Power: We have to Take it!

A new approach to promoting QAS in humanitarian and development Action

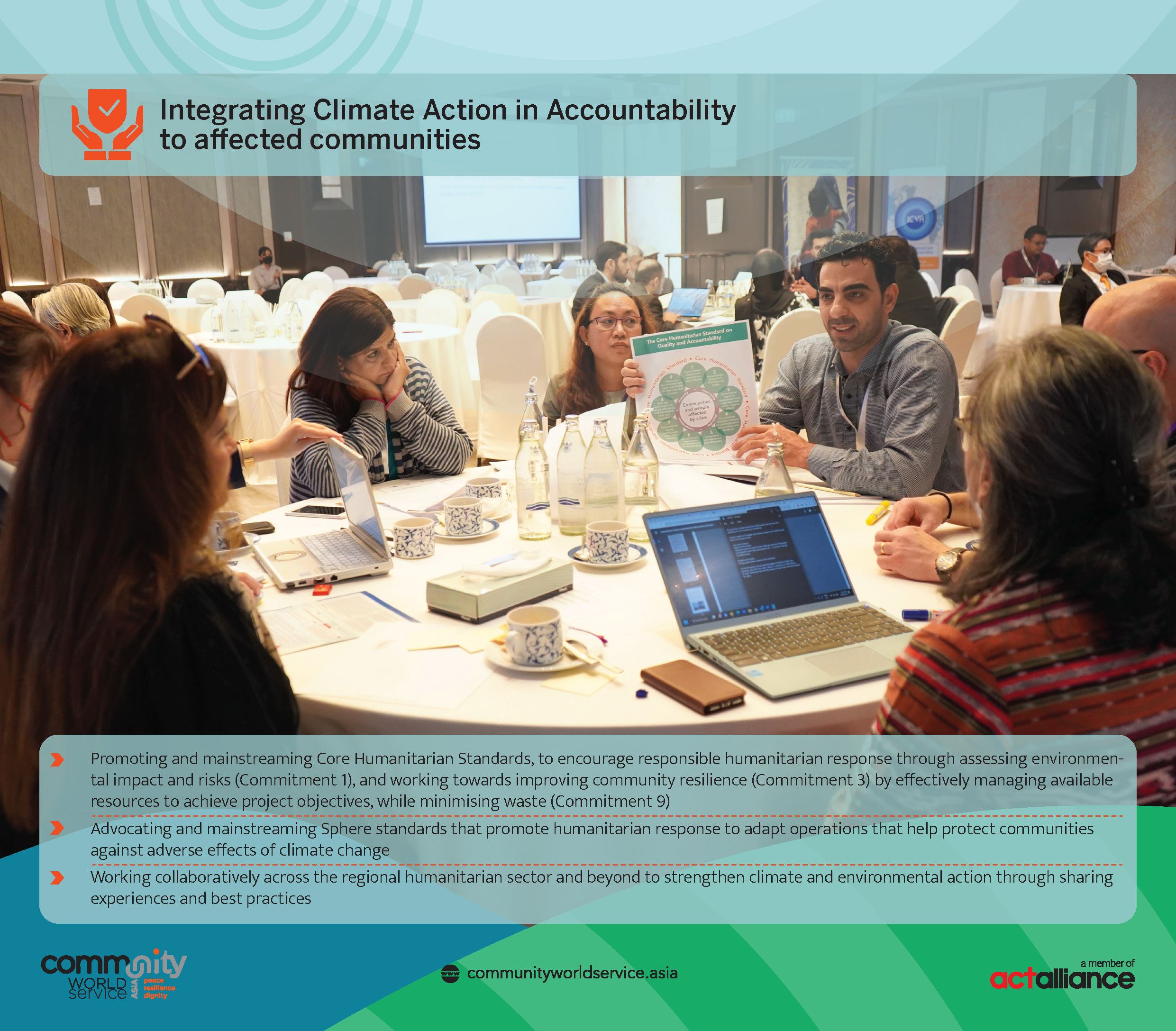

In 2022’s Regional Humanitarian Partnership Week, a five-day workshop on Quality, Accountability and Safeguarding (QAS) in Humanitarian Action, was organised by Community World Service Asia. This workshop that focused on taking a mentorship approach on promoting QAS, was engaging and innovative and was facilitated by Sylvie Robert, an Independent Consultant and expert on QAS, and co-facilitated by Rizwan Iqbal, Global Quality & Accountability Officer, ACT Alliance.

As we prepare for the upcoming annual regional QAS trainings this month, let us hear what Sylvie and Rizwan discuss in a quick chat post the workshop.

The 2022 Floods: A Wake-Up Call for Climate Action and Preparedness

#OneYearofRecovery

To put it simply: we in Pakistan are not prepared for natural disasters. One reason may be the fatalism that afflicts us and that God will be our saviour when calamity strikes. In fact, we leave much undone for God to step in to help when need be. No surprise then that during the few months of the year when our rivers run low, nomads, and sometimes even settled groups, build their homes in riverbeds. The Ravi River outside Lahore1 is a prime example of this occurring year after year.

It is also known that in the summer vacation district of Kalam (Swat), a hotel sitting right on the banks of the Swat River was swept away in the 2010 floods. The following year, the owner rebuilt his property on exactly the same spot. In 2022 it was washed away once more. There is a very slim chance that a lesson was learnt.

Downstream of Attock2, the River Indus creates a wide floodplain through Punjab and Sindh. In Punjab, the river flows virtually straight as an arrow in a south-westerly direction. But in Sindh it is an immense web of oxbows with very shallow banks. The fall of the land stretching up to almost 10 kilometres here is less than a metre. Moreover, unknowing to many, the soil of lower Sindh is virtually impermeable. Here water takes years to percolate into the aquifer.

It was seen that the water left behind by the deluge in 1987, was still sitting in the ditches by the roads five years later. In the districts of Badin and Mirpur Khas, lakes had formed where migratory birds like flamingos and pelicans were wintering in 1992. Likewise, the dry oxbows of the old bed of the Indus in upper Sindh turned into major water bodies that remained for several years.

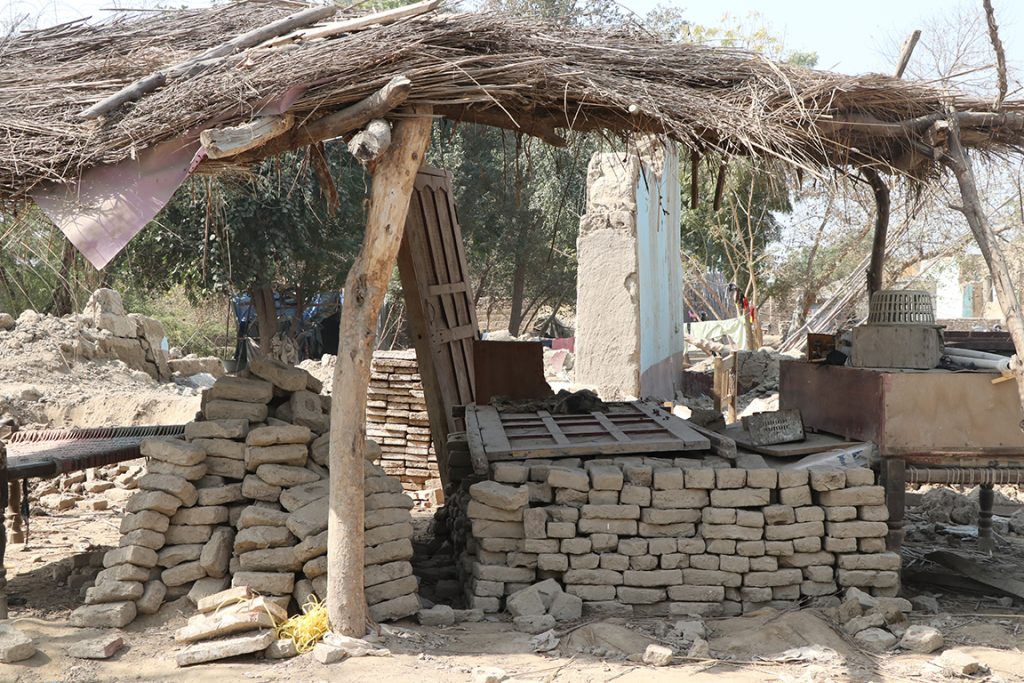

The flood of 2010-11 was one thing. In 2022, it was simply biblical. Throughout Sindh, men related that once the deluge began in July, it continued for a full forty days with short gaps in between. Whereas mud and wattle huts stood no chance under the cascade, even brick and masonry homes started to collapse after a couple of weeks. These latter are of two types. The one with a proper cement concrete slab lintel for the roof; or the less expensive one with a girder and cross strips inlaid with tiles. In many cases the walls are just one brick thick.

As the skies sent down cascades of water, the Indus too rose from the deluge in its upper reach. Millions of acres of farmland went under as the oxbows overflowed turning the land into a very sea. Date groves with their fruit ready to be picked were flooded killing off the trees at worst and best damaging the fruit. Sindh, famous for its cotton output, lost virtually all of its cotton crop. The vast vegetable patches in the floodplain that had remained dry since 2011 were drowned.

When it is not in spate3, the Indus floodplain is very fertile farmland and all along its course through Punjab and Sindh the loamy soil is used extensively for wheat and vegetables that can be harvested before the summer thaw in the mountains reaches the plains. In 2022, farmers along the river were able only to reap their wheat and collect their vegetables before May. Anything that remained on the stalk was destroyed.

This year, there was no farmer in the Sindh plains along the river who so much as made good their agricultural expenses. And since the practice has long been to make this investment on credit, thousands of farmers went under huge debts.

Loss of agriculture was something that could have been overcome and indeed the milder monsoon of 2023 has ameliorated the agricultural scene to only a little extent because when sowing of wheat commenced in December, the soil was still waterlogged. As a result, the yield was very poor in March. If submerged farmland has to be reclaimed it needs a giant effort by the government to pump out the water. Individual farmers who can afford it have been seen doing such dewatering, but the magnitude of the job is way beyond the capacity of individuals and the civil society.

However, it was the loss of housing that broke the backs of the farming communities across Sindh. With their incomes lost, they were unable to rebuild and a year after the deluge, innumerable families are still living under makeshift shelters.

The cash assistance of PKR 48,000 (Approx. USD 156) in four equal instalments to affected families under one of CWSA’s flood response projects, was some help but as Shams Din a sharecropper of village Ismail Sanjrani (Khairpur) said it was like ‘salt in the flour’, in reference to the pinch of salt added to flour before kneading. His two-room house built many years ago was a heap of bricks and clay after the deluge and the cost of full reconstruction with current inflation was PKR. 300,000. With the little help he had received, he hoped to raise the walls to lintel level. Across it, he said, he would stretch the tarpaulin that currently made his home.

Even holders of ten acres of irrigated land in the district were hardly any better off. With their agriculture completely lost, and their more spacious houses either completely razed or with just the walls rebuilding would cost way more than what poor Shams Din does not have. The hope in early 2023 was that there would be no visitation and that their agriculture would yield sufficient profits to start rebuilding.

The greater losers, however, are owners of fruit orchards. Lemon, mango and date that grow abundantly in Khairpur district yielded nothing leaving fruit farmers under huge debts. The flooding left large number of these trees not just fruitless, but dead. Some of these orchards, particularly lemon, were planted only three years before the flood and the owner had barely repaid the loan for the purchase of the trees. Just when they thought they were heading for a profitable harvest, all was lost.

In the south in Mirpur Khas district, the story is not very different. Thousands of acres of farmland now look like lakes. Here the damage was done as much by the nonstop rain as it was done by the overflowing Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD). For years this drain meant to carry effluent to the sea had been no more than a trickle. Consequently, influential landowners encroached upon its course, blocking it to create farms where historically only barren land had spread.

When the Indus overflowed and with it LBOD, towns and villages around Jhuddo went under. The damage around Jhuddo was mainly because of the unofficial damming of LBOD in its lower reach: it may have blocked tainted water flowing into the farms of the rich and powerful, but it created havoc for ordinary people.

While housing and agriculture was lost, the additional damage was done by the overflowing of effluent from LBOD. The common complaint here, as in Khairpur and other areas, was that flooding had tainted their hand pumps. Thousands of people were therefore drinking poisoned water causing skin and gastro-intestinal diseases. Primary health care units were unable to cope with the flood of humanity pouring in without outside help. Health camps established by CWSA provided some succour. The disaster was simply too great and widespread for its effect to be mitigated by these heroic but small initiatives.

While the civil society has been hard at work, their effort is still too little compared to the impact the floods of 2022 has had on the people of Sindh. A greater effort is needed to bring back people’s lives to normal.

- Capital city of Punjab province. The second largest city in Pakistan and 26th largest in the world, with a population of over 13 million.

- It is the headquarters of the Attock District and is 36th largest city in the Punjab and 61st largest city in the country, by population.

- A sudden flood in a river

From Seeds to Stews

Kitchen Gardens: A sustainable model for food security & diversity for the people of Umerkot

“We, none of us in this village, ever thought of keeping a kitchen garden. It was something beyond our thinking,” with these words Sohdi of village Charihar Bheel echoes the voice of thousands of women and men across the desert area of Umerkot. This is what they believed until Community World Service Asia (CWSA) launched the training sessions on kitchen gardening.

Now, even though they live in a sand desert, the communities of Umerkot are all farmers and livestock keepers. Their practice has long been to plough their fields in late June and sow the seeds of their seasonal crops in anticipation of the coming monsoon. For vegetables, however, they made a separate set of furrows on one side of the main field. Because the fields are outside the village, sometimes a little way off too, there was no way of watering them. Therefore, while hardy crops like guar beans, mong or millets could survive until the rains begin in July, the vegetable seeds needed watering.

Consequently, the seeds that made it through until the first shower produced a small crop of vegetables to last a few days. If the rains were good, the farmer’s family had a supply of wholesome, organic vegetables for a few weeks. And then the plants withered. That is, a farming family in Umerkot had vegetables only once a year during the first fall of summer rains. Of course there is the hardy chibhar (Cucumis melo agrestis), wild and abundant in the summer whose miniature melon-like fruit can either be stewed fresh or dried. There is also the kandi (Prosopis cinerara) tree with its leguminous seed pods that make another nourishing stew known as singri. And then, during the monsoon, the people of Umerkot have the luxury of a fine and rather abundant mushroom, even if for a short while.

This, then, is the limit of their fresh local vegetables. The other source is purchasing from the city. This is done only when someone is in town for work; to go especially for vegetables would make the purchase unaffordable. Since there is no way to stock them fresh at home, the purchase is usually for two or three days and consumed in this period before the vegetables go off. Unsurprisingly, the usual diet in Umerkot was wheat or millet flatbread with chilli paste washed down with water. Variety in diet was virtually unknown for the most part of the year.

Yet, as Sohdi says, no one ever thought of preparing a patch nearer to their home to have a regular supply of fresh vegetables.

The kitchen gardening intervention, by Community World Service Asia, Canadian Foodgrains Bank (CFGB) and Presbyterian World Service & Development (PWS&D), with relief following the drought of 2021 introduced the farmers of Umerkot to the idea nobody had thought of before: a small patch right by the house for vegetables. This is always in the charge of the woman of the household and speaking with several of them one can learn how to manage a kitchen garden for fresh vegetables: water the patch and keep it moist for three days before adding animal manure. Then prepare the furrows and plant the seeds. Flood irrigation is a wasteful idea of the past; watering should be done with a used PET1 cola bottle with its cap punctured to deliver a small stream in the root of the sprouting plant. And the kitchen garden is ready to supply vegetables two to three weeks after the sowing.

An hour distance away, in New Subani, the very vocal Dai who is a member of every committee in the village, has no doubt how well her kitchen garden serves her family. She says she planted her first patch in March 2022 with okra, chibhar, guar, cucumber, squash and zucchini. It was very fruitful and she has never looked back since. The garden sowed in March lasted until the middle of May before withering away in the arid pre-monsoon heat. “Everyday we had vegetables with our chapatti which beats chilli paste any time. And my crops of squash, okra and zucchini were so abundant, I gave away vegetables gratis to my neighbours,” she says.

According to Dai, the fear of what to feed a visitor was banished from her life after she began her kitchen garden. That year, Dai did her second batch in July. The rains were very good and her garden lasted well into August. She kept the seeds from her vegetables and with some supplied by CWSA, planted a very successful kitchen garden again in March 2023. In July, she yet again had a little garden coming along well after the first rain of the season.

Earlier, every year Dai planted a small patch of vegetables by the side of her agricultural plot. It was always a dicey business. To get some little out of it was considered good fortune, and that only when it rained on time. But the CWSA training on kitchen gardening and this idea of having the patch next to her home has made her a supplier of free vegetables to her neighbours and anyone who comes asking.

Far away in Kachbe Jo Tar, another village in the same district, school teacher Bhammar Lal Bheel tends his wife’s kitchen garden. He speaks of the joy of having fresh spinach, okra, eggplant, marrow and pumpkin and says that the variety of the menu in his home has given him more energy than he ever had. “The millet chapati (unleavened flatbread) slides down very easily when taken with a vegetable stew,” he says with a smile.

Being the man who goes frequently into town, he knows the rate of vegetables and recounts it for the listener. Two days’ worth of greens for a family of eight members like his put one back by at least PKR 800 (Approx. USD 2.75). And even then the vegetables were not very fresh. He also knows that they are treated with harmful chemical pesticides. But now with their own kitchen garden the family has fresh, straight off the stalk vegetables that are one hundred percent organic too. It is free because CWSA provided his wife the seed to augment her stock she saves from her previous garden.

Bhammar Lal produced a MUAC (Mid Upper Arm Circumference) measuring tape. He says he first of all began by measuring MUAC in his own family and was surprised by the progressive increase in size among the children in the weeks following the addition of vegetables to their diet. Then he went around the village comparing the measurements of those families with kitchen gardens with those who did not have them. “There was such a clear difference, not only in children’s MUAC, but of grown women as well. That speeded up my personal campaign to encourage more and more kitchen gardens,” he says with visible pride. “It’s the vitamins!”

Bhammar Lal says his wife participated in the CWSA training sessions and learned how to make the best of the little vegetable garden. But there are women who were not part of the training and who are not in on this little open secret. “I go around the village instructing other women on how to make a kitchen garden. And then I follow up a few days later and if they are not at it, I encourage them to at least try it out,” he says. He is happy that by his effort, there are many more kitchen gardens in the village. To paraphrase Sohdi again: everyone is happy because chapati goes down so well with stewed vegetables.

Not too far, in Rohiraro village, the ever-smiling Gauri points out one effect of the kitchen gardens that have now sprouted almost all over the village. And this may not have been foreseen by the NGO: with the vegetable patch to look after, women have not gone to ‘Sindh’ (as they refer to the irrigated districts to the west) last year and again in 2023. In consequence, children who leave school in March to travel with the family and return after the summer vacations have had two full years of education.

In Gauri’s view, the real winner is education. That is even more important than just good health.

- Polyethylene Terephthalate

Sphere Regional Focal Point Forum for Asia, Bangkok, December 2022

Quality and Accountability Learning Camp

Training on: Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management

When: 14th-16th November, 2023

Where: Peshawar, KPK

Language: Urdu & English

Interested Applicants Click Here to Register

Last Date to Apply: 10th October, 2023

Rationale:

In an era defined by dynamic shifts in development and humanitarian approaches, the essence of community engagement has taken on global significance, both upstream and downstream. This evolution has reshaped how we conceptualize, plan, and gauge impact within the ever-changing world ecosystem.

The “Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management Training” emerges as the compass guiding professionals through the intricacies of modern impact assessment, along the project plan. By unearthing advanced methodologies, pragmatic frameworks, and illuminating case studies, this training empowers participants not only to measure impact but also to strategically align interventions for comprehensive community advancement objectives.

Training Objectives and Contents

This program is about navigating the entire project lifecycle with finesse. From meticulously crafting program design to seamless implementation, rigorous monitoring, and impactful assessment, we encompass ensuring that projected outcomes become documented realities.

By joining this training, the impact of your interventions becomes your ally, from inception. Discover how to harness cutting-edge data collection and analysis tools that empower your impact measurement. Our training doesn’t just stop at knowledge – it’s a bridge to practicality. Real-world exercises, tailored to the times with social distancing in mind, weave seamlessly with expert lectures and the invaluable exercises for experience sharing by eminent leaders in the development and humanitarian sector. With post-training coaching and mentoring bolstering 30% of participant organizations, your growth is our relentless pursuit. Dive into the heart of impact management as we delve into:

- Mastering program design with an impact and learning lens

- Commanding Theory of Change/Change Models for dynamic interventions

- Immersing in a spectrum of impact measurement and evaluation tools, from data and tech powered analysis solutions to remote data collection innovations

- Fusing Quality and Accountability standards with humanitarian programs, forging a path of excellence

- Pioneering peer support action plans and nurturing coaching/mentoring avenues

Number of Participants

We encourage you to join an exclusive group of 20 change-makers, by accepting applications from diverse backgrounds, including women, differently abled individuals, and aid workers from ethnic/religious minorities. Priority is given to those from under-served areas. Deadline to Apply is by October 10, 2023.

Selection Criteria

- Primary responsibility for monitoring and impact assessment /MEAL staff at the project

- and/or organizational levels

- No previous exposure/participation in trainings on Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Measurement

- Mid or senior level manager in a civil society organization, preferably field staff of large CSOs or CSOs with main office in small towns and cities

- Participants from women led organizations, different abled persons, religious/ethnic minorities will be given priority

- Willing to pay a fee PKR 20,000 for the training. Exemptions may be applied to CSOs with limited funding and those belonging to marginalized groups. Discount of 10% on early registration by 05 October,2023 and 20% discount will be awarded to women participants

About Community World Service Asia

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) is a humanitarian and development sector organization, registered in Pakistan, head-quartered in Karachi and implementing initiatives throughout Asia. CWS/A is a member of the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) Alliance, a member of SPHERE and their regional partner in Asia and also manages the ADRRN Quality & Accountability Hub in Asia.

Facilitator/Lead Trainer: Mr. Mohammad Tayyab

Mohammad Tayyab specializes in planning and accountability measures of projects and programs within the development and humanitarian sectors. With over 20 years experience of working for development sector projects, programmes and institutions, and a strong background in designing and conducting social research and MEAL assignments, he has successfully contributed to the sector in Pakistan and in other countries. He has evaluated the impacts of programs, synthesizing lessons learned, and fostering a knowledge management culture to empower institutions.

One of Mohammad’s key strengths within the MEAL processes is his ability to effectively engage with diverse stakeholders, both individually and in group /institutional settings. His work has also played a pivotal role in facilitating organizational development for a wide range of international and national NGOs, bilateral and multilateral organizations, as well as corporate companies. In addition to his project and program planning expertise, Mohammad has conducted extensive research in social and institutional aspects. His research encompasses a broad spectrum, including public sector institutions, corporate companies, and social organizations. Within his area of expertise, which includes climate change, livelihood, gender, DRR and humanitarian response, he has particularly excelled in enhancing institutional and program effectiveness within these domains.

Medical Aid: Not a Day too Soon

Medical Aid: Not a Day too Soon

Village Dharshi Bhagat lies by the road connecting Samaro town with Samaro Road; the latter being the town’s railhead where the old abandoned metre-gauge railway station still stands for the first two weeks after it started in late July, the rain did not stop for a minute. Thereafter it continued to teem down with brief intervals lasting never more than some minutes until the village went under a metre of water.

Twenty-five-year-old Heeru was only days from delivering her baby when it started. As the water rose, she and some other women made a desperate run to save whatever little cotton they could from the fast drowning field they had so carefully tended the land they worked as labourers. The struggle in mud and water was worth only a few thousand rupees.

With the village going under water, she and her family left their home and the fields and moved to the only stretch of road that was above the dark water. For three months, they lived under a makeshift shelter of bamboo poles holding up plastic sheeting for a roof. It was good fortune that Heeru had salvaged some cotton and there was some cash for food because in the time of the rising waters, she gave birth to her second child, a daughter. When her pains began, her husband hired a motorcycle and ferried Heeru to the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road where she fortunately got the attention of the doctor and a safe delivery.

Not long after the birth of the child the meagre cash in her kitty ran out and her family subsisted on chilli paste and roti. Their one goat provided a small amount of milk daily. It was a hard life for the family, especially so for the young lactating mother.

Heeru recounted how her firstborn, a son, had died two years ago aged just four months. The child had gone down with fever and convulsions and though the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road was just 4 km away, the parents were tardy in taking him there. For five days the poor child suffered and when they eventually did get to the BHU, the doctor could do nothing to save the baby.

For some inexplicable reason, seeking medical assistance was simply not a priority for these poor people. They still relied on folk medicine and even considered milk tea some sort of panacea.

Dharshi Bhagat, who gives his name to the village, said Heeru’s husband was lucky to be able to rent a motorcycle because shortly after, the only transport capable of plying on the submerged roads were big four-wheel drive vehicles. An ailing person had to be carried either on a string bed or piggyback all the way to the units either in Samaro or Samaro Road. And this was a time of rampant disease. Fever, skin infections and diarrhoea were raging in the makeshift camp strung out along the road. In that desperate time of zero income, men were seen carrying the ailing to the BHU.

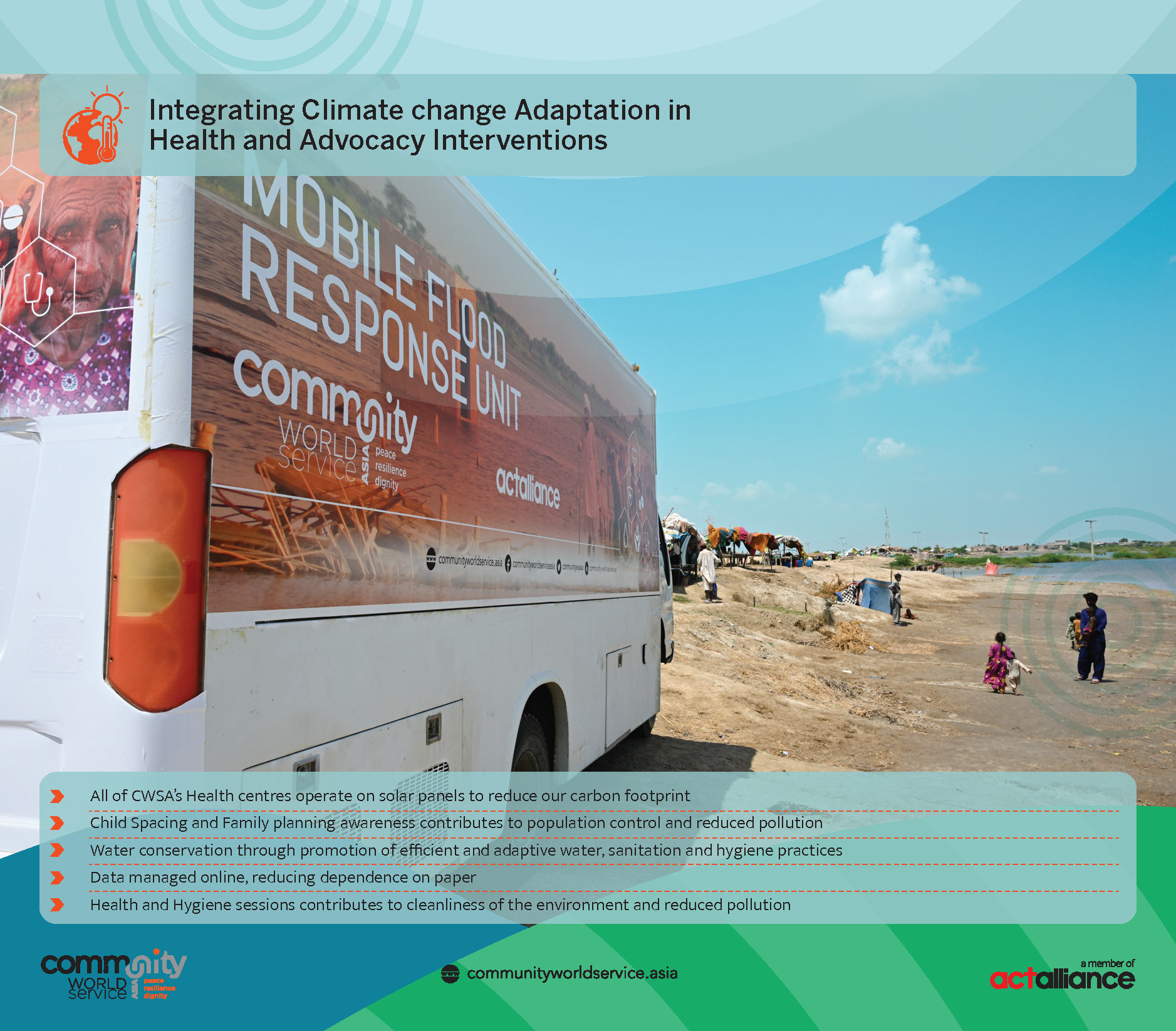

In mid-October, the first Community World Service Asia’s medical mobile unit reached this village. The village was still submerged and the mobile unit had to be parked on the road, the only strip of land free of water. Dharshi Bhagat said this came not a day too soon for who would not have appreciated this gratis service at the doorstep in that time of great adversity.

Lady Health Visitor Farkhanda said the mobile unit had been on the road for ten weeks moving from village to village and treated on average a hundred and fifty patients every day. On the first visit to Dharshi Bhagat, they had a similar number between nine in the morning and three in the afternoon. Referrals of more complicated cases was made to the Samaro town hospital. Common complaints were malaria, water-borne gastro-intestinal, eye and skin infections. This time around, respiratory tract infections had increased and the demand was for ‘pills for strength’, as multivitamin tablets are referred to.

Outside, among the crowd of men waiting to consult the doctor Bhoomo said he felt weak and his ‘liver burned’ and showed a handful of blister-packed multivitamin tablets and an antacid.

“The first time the medical van visited our village, I was suffering from the same, but I had been out cutting mesquite to sell in neighbouring villages and I missed my chance to see the doctor,” said Bhoomo. For him his suffering was secondary. Most essential was for him to make some little cash for food.

Why hadn’t Bhoomo gone to the hospital in town during all this time? “I have no money, the fare out and back is Rs 40, and after I spend a day cutting mesquite, there is only enough cash to purchase food for my family of nine. I cannot afford to go to town.”

On the second visit in mid-November the mobile health unit had in just two hours treated one hundred and thirty patients. And an equal number waited patiently outside. Some like Dheero said they had no complaint and had come only to watch the goings on; most others complained of stomach ache and fever. Nearly all of them had either simply suffered stoically or experimented with folk medication to no effect. The lament was the same all around: they had no money to visit the hospital in town. And they could not afford to take time off from their struggle to earn some money.

Listening to the very vocal Kasturi, suffering in silence seemed to come naturally to them. She had a reasonable income from working as a seamstress while her husband was a door-to-door clothier. Their once comfortable life was now reduced straitened circumstances.

“The crops have all been destroyed. There is no work and therefore no money. Who can order new clothing in these times? The Lord is kind, I took great precautions and my three children did not fall ill, but families with illness could either feed themselves one, or at most two, meals a day. They did not have the means to make frequent trips to the Samaro hospital.”

Dharshi Bhagat was right: the mobile unit had come not a day too soon.