The 2022 Floods: A Wake-Up Call for Climate Action and Preparedness

#OneYearofRecovery

To put it simply: we in Pakistan are not prepared for natural disasters. One reason may be the fatalism that afflicts us and that God will be our saviour when calamity strikes. In fact, we leave much undone for God to step in to help when need be. No surprise then that during the few months of the year when our rivers run low, nomads, and sometimes even settled groups, build their homes in riverbeds. The Ravi River outside Lahore1 is a prime example of this occurring year after year.

It is also known that in the summer vacation district of Kalam (Swat), a hotel sitting right on the banks of the Swat River was swept away in the 2010 floods. The following year, the owner rebuilt his property on exactly the same spot. In 2022 it was washed away once more. There is a very slim chance that a lesson was learnt.

Downstream of Attock2, the River Indus creates a wide floodplain through Punjab and Sindh. In Punjab, the river flows virtually straight as an arrow in a south-westerly direction. But in Sindh it is an immense web of oxbows with very shallow banks. The fall of the land stretching up to almost 10 kilometres here is less than a metre. Moreover, unknowing to many, the soil of lower Sindh is virtually impermeable. Here water takes years to percolate into the aquifer.

It was seen that the water left behind by the deluge in 1987, was still sitting in the ditches by the roads five years later. In the districts of Badin and Mirpur Khas, lakes had formed where migratory birds like flamingos and pelicans were wintering in 1992. Likewise, the dry oxbows of the old bed of the Indus in upper Sindh turned into major water bodies that remained for several years.

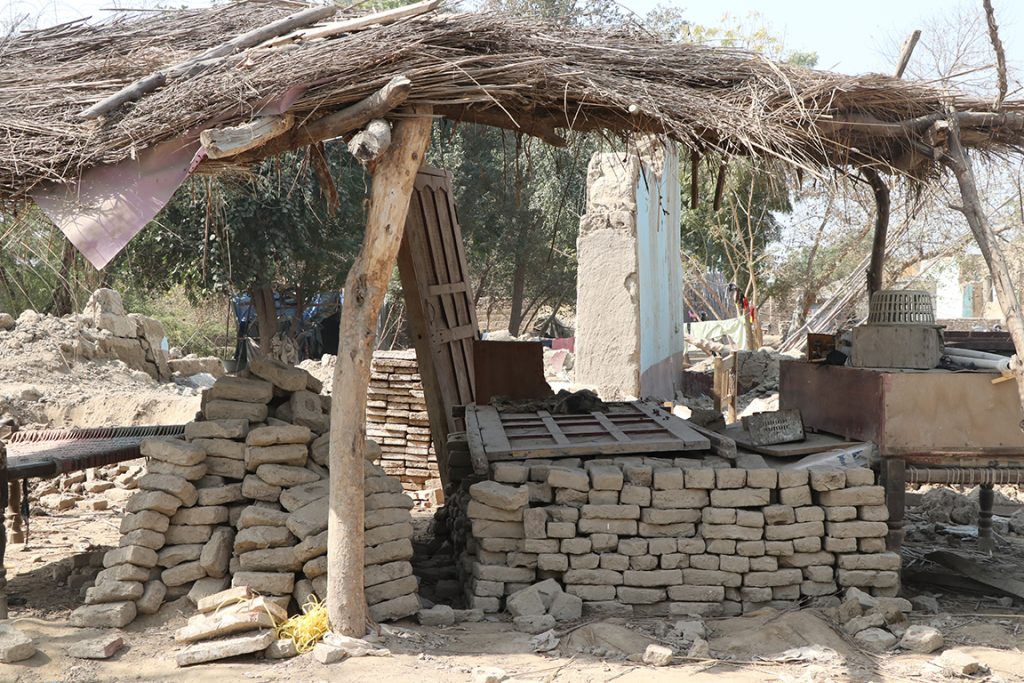

The flood of 2010-11 was one thing. In 2022, it was simply biblical. Throughout Sindh, men related that once the deluge began in July, it continued for a full forty days with short gaps in between. Whereas mud and wattle huts stood no chance under the cascade, even brick and masonry homes started to collapse after a couple of weeks. These latter are of two types. The one with a proper cement concrete slab lintel for the roof; or the less expensive one with a girder and cross strips inlaid with tiles. In many cases the walls are just one brick thick.

As the skies sent down cascades of water, the Indus too rose from the deluge in its upper reach. Millions of acres of farmland went under as the oxbows overflowed turning the land into a very sea. Date groves with their fruit ready to be picked were flooded killing off the trees at worst and best damaging the fruit. Sindh, famous for its cotton output, lost virtually all of its cotton crop. The vast vegetable patches in the floodplain that had remained dry since 2011 were drowned.

When it is not in spate3, the Indus floodplain is very fertile farmland and all along its course through Punjab and Sindh the loamy soil is used extensively for wheat and vegetables that can be harvested before the summer thaw in the mountains reaches the plains. In 2022, farmers along the river were able only to reap their wheat and collect their vegetables before May. Anything that remained on the stalk was destroyed.

This year, there was no farmer in the Sindh plains along the river who so much as made good their agricultural expenses. And since the practice has long been to make this investment on credit, thousands of farmers went under huge debts.

Loss of agriculture was something that could have been overcome and indeed the milder monsoon of 2023 has ameliorated the agricultural scene to only a little extent because when sowing of wheat commenced in December, the soil was still waterlogged. As a result, the yield was very poor in March. If submerged farmland has to be reclaimed it needs a giant effort by the government to pump out the water. Individual farmers who can afford it have been seen doing such dewatering, but the magnitude of the job is way beyond the capacity of individuals and the civil society.

However, it was the loss of housing that broke the backs of the farming communities across Sindh. With their incomes lost, they were unable to rebuild and a year after the deluge, innumerable families are still living under makeshift shelters.

The cash assistance of PKR 48,000 (Approx. USD 156) in four equal instalments to affected families under one of CWSA’s flood response projects, was some help but as Shams Din a sharecropper of village Ismail Sanjrani (Khairpur) said it was like ‘salt in the flour’, in reference to the pinch of salt added to flour before kneading. His two-room house built many years ago was a heap of bricks and clay after the deluge and the cost of full reconstruction with current inflation was PKR. 300,000. With the little help he had received, he hoped to raise the walls to lintel level. Across it, he said, he would stretch the tarpaulin that currently made his home.

Even holders of ten acres of irrigated land in the district were hardly any better off. With their agriculture completely lost, and their more spacious houses either completely razed or with just the walls rebuilding would cost way more than what poor Shams Din does not have. The hope in early 2023 was that there would be no visitation and that their agriculture would yield sufficient profits to start rebuilding.

The greater losers, however, are owners of fruit orchards. Lemon, mango and date that grow abundantly in Khairpur district yielded nothing leaving fruit farmers under huge debts. The flooding left large number of these trees not just fruitless, but dead. Some of these orchards, particularly lemon, were planted only three years before the flood and the owner had barely repaid the loan for the purchase of the trees. Just when they thought they were heading for a profitable harvest, all was lost.

In the south in Mirpur Khas district, the story is not very different. Thousands of acres of farmland now look like lakes. Here the damage was done as much by the nonstop rain as it was done by the overflowing Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD). For years this drain meant to carry effluent to the sea had been no more than a trickle. Consequently, influential landowners encroached upon its course, blocking it to create farms where historically only barren land had spread.

When the Indus overflowed and with it LBOD, towns and villages around Jhuddo went under. The damage around Jhuddo was mainly because of the unofficial damming of LBOD in its lower reach: it may have blocked tainted water flowing into the farms of the rich and powerful, but it created havoc for ordinary people.

While housing and agriculture was lost, the additional damage was done by the overflowing of effluent from LBOD. The common complaint here, as in Khairpur and other areas, was that flooding had tainted their hand pumps. Thousands of people were therefore drinking poisoned water causing skin and gastro-intestinal diseases. Primary health care units were unable to cope with the flood of humanity pouring in without outside help. Health camps established by CWSA provided some succour. The disaster was simply too great and widespread for its effect to be mitigated by these heroic but small initiatives.

While the civil society has been hard at work, their effort is still too little compared to the impact the floods of 2022 has had on the people of Sindh. A greater effort is needed to bring back people’s lives to normal.

- Capital city of Punjab province. The second largest city in Pakistan and 26th largest in the world, with a population of over 13 million.

- It is the headquarters of the Attock District and is 36th largest city in the Punjab and 61st largest city in the country, by population.

- A sudden flood in a river