The Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) has issued a heatwave alert, forecasting a sharp rise in temperatures across much of the country. Daytime temperatures are expected to surge significantly, with Sindh and Balochistan projected to experience an increase of 6 to 8°C above normal levels. In some areas of Sindh, temperatures could soar as high as 46 to 48°C, posing serious risks to public health and well-being1. Authorities urge residents to take necessary precautions to mitigate the impact of extreme heat.

In Sindh’s Umerkot district, the heatwave is already intensifying, with temperatures expected to reach 47°C in the coming days. Unusually, this spike has occurred nearly a month earlier than the typical onset in mid-May, with extreme conditions beginning in mid-April. The heatwave is projected to persist through April, May, and June2.

Impact on Vulnerable Populations

The heatwave is disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups, including pregnant and lactating women, children, the elderly, persons with disabilities, individuals with chronic health conditions, and daily wage labourers exposed to the sun for prolonged periods. In Umerkot, these risks are exacerbated by limited access to clean drinking water, electricity, and healthcare services. Women, in particular, face increased burdens during such climate extremes, necessitating urgent, gender-sensitive interventions.

While no casualties have been reported so far, communities are facing major disruptions to daily life. Many residents remain indoors during peak afternoon hours, and CWSA health dispensaries have recorded a sharp decline in patient visits after 12 PM, underscoring the severity of the conditions.

Identified Humanitarian Needs

Several critical humanitarian needs have been identified to safeguard the most vulnerable populations and reduce the impact of extreme heat:

Emergency Health Services

- Deployment of Mobile Medical Units to reach pregnant women, children, the elderly, and individuals with chronic illnesses in remote areas.

- Provision of first aid and hydration therapy for those experiencing symptoms of heatstroke and dehydration.

- Increased staffing and supplies at existing health dispensaries to manage potential surges in heat-related illnesses.

Access to Safe Drinking Water

- Installation of temporary water stations in public spaces and high-risk areas.

- Distribution of water containers and purification tablets to households with poor water access.

- Ensuring clean water supply at schools, health facilities, and community centres.

Community Awareness and Behavioural Change

- Mass awareness campaigns on heat safety, symptoms of heat exhaustion/stroke, and dehydration prevention.

- Targeted education sessions through Village Management Committees (VMCs), particularly for women and children.

- Promotion of protective behaviours, such as avoiding outdoor activities between 11:00 AM–4:00 PM, wearing light clothing, and staying hydrated.

Gender-Sensitive Support

- Inclusion of women’s specific needs, especially for pregnant and lactating mothers.

- Safe and private access points for women at water stations and medical services.

- Distribution of IEC materials tailored for women and girls on self-care during heatwaves.

Infrastructure and Shelter Support

- Setting up shaded relief centres and cooling zones in public areas, markets, and near labour sites.

- Distribution of cooling aids like fans, umbrellas, and cloth shades for households.

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) Response

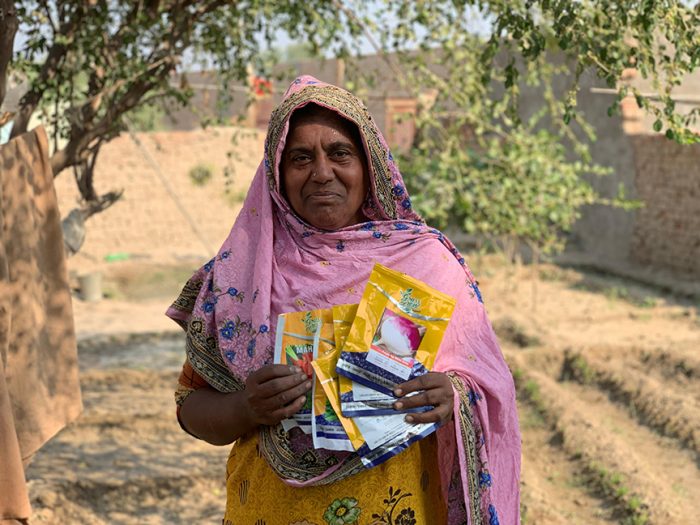

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) has launched a targeted heatwave response in Umerkot, Sindh, in collaboration with the Village Management Committees (VMCs) that it engages with at the community level. Awareness sessions are being held with men, women, and children to share critical information on hydration, heat protection, and behavioural safety—particularly urging residents to avoid outdoor activities between 11:00 AM and 4:00 PM.

The VMCs are playing a pivotal role in strengthening community resilience by disseminating life-saving information and ensuring protection for the most at-risk populations. CWSA is also distributing information, education, and communication (IEC) materials and offering first aid to affected individuals through its three operational health dispensaries.

In coordination with the District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA), District Administration, and Health Department, CWSA is supporting plans to establish relief camps at hospitals and key public locations. These camps will provide access to clean drinking water, shade, and emergency medical care. Additionally, CWSA is prepared to deploy its Mobile Health Units, equipped with essential supplies, to provide outreach services across the desert union councils of Umerkot.

To address the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves in the region, CWSA aims to implement long-term resilience measures:

- Establishment of community-based heatwave preparedness camps.

- Creation of permanent heat resilience hubs in high-risk areas.

- Training of Lady Health Workers and community volunteers in first aid, hydration therapy, and early detection of heat-related illness.

- Regular early warning sessions and public awareness campaigns.

- Collaboration with PDMA/DDMA and local media to ensure timely dissemination of heatwave alerts.

- Ongoing community education on dehydration prevention, heatstroke symptoms, and protective behaviours.

Contacts

Shama Mall

Deputy Regional Director

Programs & Organisational Development

Email: shama.mall@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Palwashay Arbab

Head of Communication

Email: palwashay.arbab@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4