Nestled between the irrigation provided by the Nara branch of the Indus on one side and the grey-white sand dunes on the other, Behram Mallah is a village of boatmen from an ancient time when the Nara was the most convenient mode of transport. Their sailboats with their high sabot-shaped prows, once cleaved the waters from its southernmost navigable point to Rohri, where it takes off from the mighty Indus. They transported food, agricultural produce and fruit to the many river ports whose remnants still dot the meandering route of the Nara.

However, as time passed, roads were built and buses began to replace the camels that once plodded along leisurely. The mariners of old were forced to adapt. About eight years ago, Mushtaq’s great-grandfather abandoned his boat to become a small-time farmer. By the time Mushtaq grew up, the small plot of land belonging to senior Mallah had been divided repeatedly and even sold off in parcels to enable his father to educate his three sons up to high school and run a tube well boring and installation service. Today, Mushtaq’s father is landless, except for the house where he lives with his sons.

In 2020, Mushtaq married Nafisa while he worked as a daily wage construction labourer. He did not confine his wife to housework but instead sent her to the nearby middle school, where she studied in grade nine. The couple knew that becoming wealthy was a distant dream, but they aspired to start a family that could one day improve their circumstances.

Three years passed and young Nafisa was still unable to conceive. They knew of a well-known gynaecologist in Khairpur, but getting there by local bus required a six-hour journey, followed by an overnight stay due to the long queue of patients at the clinic. Alternatively, they could hire a taxi for PKR 12,000 (approx. USD 43) for a round trip and return home the same evening after seeing the doctor. The couple opted for this option.

Nafisa shyly recounts her experience. “The doctor’s fee was PKR 800 (approx. USD 2.8) and she prescribed medication that was only available at her clinic’s pharmacy. This cost us PKR 8000 (approx. USD 29). We were told to return after a month.” Although the doctor’s consultation fees were modest the medication cost was substantial.

Mushtaq explains that they did not have ready cash and borrowed money from his father, brothers and uncles to cover these costs. Over nearly a year, the couple made around ten trips each costing them about PKR 22,000 (approx. USD 79). Each time they returned with a bag full of medication costing PKR 8000 (approx. USD 27), all on borrowed money.

Despite the doctor’s assurance, Nafisa did not conceive. The couple was also advised to undergo expensive tests at the doctor’s in-house laboratory.

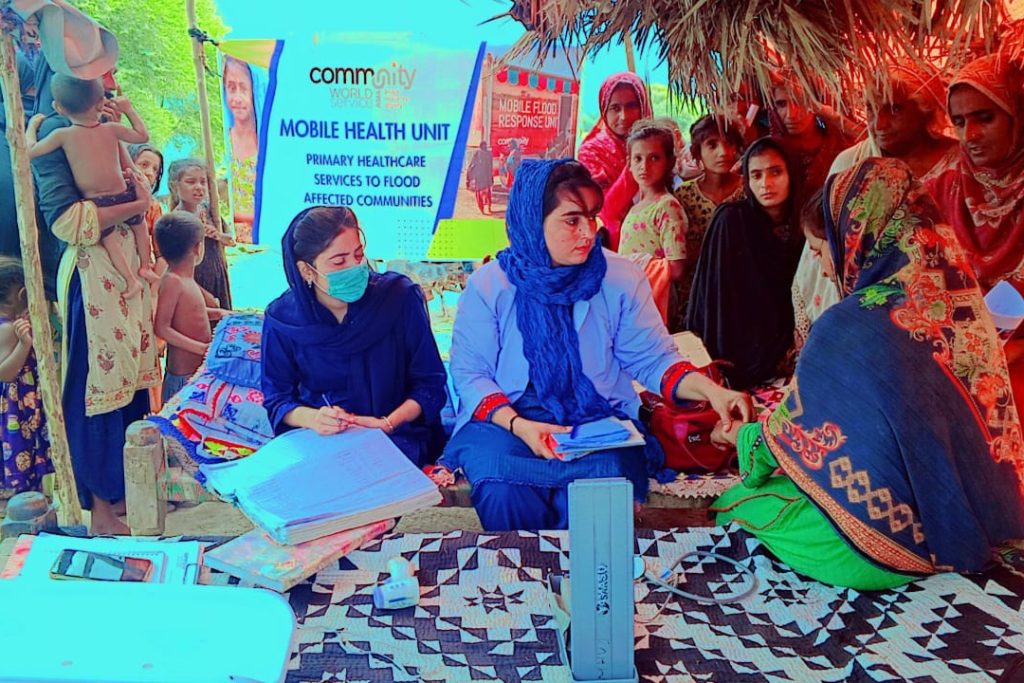

Mushtaq then heard about a container stationed at the abandoned health centre in Choondko, staffed by a Lady Health Visitor (LHV) Rabia, who was on call 24 hours a day. In March 2023, the couple, unfamiliar with the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) and Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and their work, visited the centre. They were advised to return the next day for a consultation with Dr Sabeen. Choondko, just 12 kilometres from their home, was more accessible and affordable than the ardous trip to Khairpur.

Nafisa is unsure about the exact methods employed by Dr Sabeen and Rabia, but after the second visit, and with no medication expense and free ultrasound, she became pregnant. By March 2024, little Ramesha was two months old, bringing immense joy and hope to her parents. Mushtaq recounts that there was only so much his family could lend him, so he had to borrow PKR 80,000 (approx. USD 287) on interest to cover the cost of the trip to Khairpur. Although he has repaid PKR 110,000 (approx. 394), he still owes PKR 30,000 (approx. USD 107).

The final twist in Nafisa and Mushtaq’s story came when, at full-term, the expectant mother was told during her visit to the centre that she needed specialised care due to complications expected during delivery. The Choondko centre recommended a clinic in Sukkur, but the couple opted for the “well-known” doctor in Khairpur, paying an additional PKR 40,000 (approx. USD 143) for the delivery.

As the reputation of the doctors at Choondko and Nara Gate spread, the patient traffic to the “well-known” doctor’s clinic decreased. Even after having her delivery performed by the famous doctor, Nafisa has continued to visit Choondko for check-ups with Dr Sabeen.