The first step of a learning journey on ‘Quality, Accountability to Affected Populations and Safeguarding’ kick started on February 1, 2022. A series of Virtual Learning Sessions and a Coaching Lab will run over a course of six months (January to June 2022)

A learning journey on Quality, Accountability and Safeguarding

Virtual Learning Sessions: LEARN, UPDATE, PANEL, CLINIC, IMPROVEMENT PLANS

Coaching Lab – Capitalisation of Experiences – Learning for the future

As part of this process, four Virtual Learning Sessions are jointly hosted and organised by Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and ZOA, for the Syria Joint Response (Cordaid, Dorcas, Oxfam, TDH Italy, ZOA and local partners), supported by the Dutch Relief Alliance. Other partners are also involved such as ACT Alliance, Act Church of Sweden, ADRRN’s Quality and Accountability (Q&A) Hub, CHS Alliance, International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA) and Sphere.

This initiative aims to bring together committed humanitarians who are leaders in promoting and implementing Quality and Accountability and its relevant standards and tools throughout the project/programme cycle. The primary goal is to update them on the latest developments and tools around people centred approaches to quality and accountability, and facilitate localisation, learning and contextualisation in the humanitarian, development and peace nexus.

While sharing the strategy of the session, Sylvie Robert, who designed this learning strategy and is the lead facilitator, said, “We are all part of this learning journey. We will work together to design improvement plans in a realistic manner, tailored to your context, and provide coaching to monitor these plans to see how we are implementing what we have discussed and agreed to improve. Along the process, we will capitalise experiences at individual and organisational levels and across different organisations and regions. The learning will allow to design the next steps of the journey.”

Why are we here together?

“During the Virtual Learning Sessions, we will review what is available in terms of standards and tools, as well as how we can apply and use these across the project or programme cycle,” shared Sylvie.

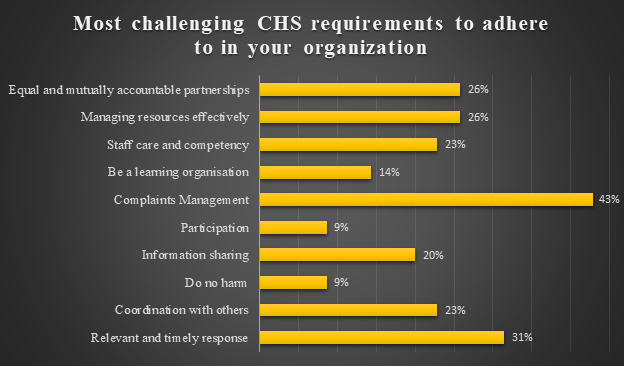

65% of the participants joined the session to better understand Quality, Accountability, and Safeguarding, while 30% joined to identify practical ways of mainstreaming Quality, Accountability and Safeguarding. The remaining 5% aim to improve their programming skills.

Forty-one humanitarian and development practitioners from Asia and the Middle East participated in the first half-day Virtual Learning Session ‘LEARN’ that gave participants a platform to share experiences from a wide array of diverse locations and organisations.

The session commenced with an introductory video of the Core Humanitarian Standard.

ASKs: While applying Quality and Accountability in your work, what limitations and opportunities are you facing in your specific working context? What key actions must be undertaken to uphold Quality and Accountability?

In response to the questions, participants reviewed, in small groups, good practices, challenges, and gained insights of different humanitarian networks and communities working on the ground on the application of Q&A.

While sharing key insights from the discussion, Qamar Iqbal from Pakistan said, “Three critical components were underlined to ensure quality and accountability in project intervention: participation, coordination, and communication. Engagement of all stakeholders in every phase of the project cycle management ensures participation of all. Likewise, effective coordination and communication of goals, expectations, successes and challenges are fundamental tenets of quality & accountability. Communities must be clear on the existing complaint response mechanism in place. To use the mechanisms in place efficiently and effectively, all processes and procedures should be properly explained to the necessary stakeholders.”

In the implementation phase, participants agreed that organisations should be able to adapt to contextual and situational changes. “Engaging communities and enabling their effective participation during the planning and assessment phases is a critical challenge for many organisations. To address this concern, several organisations are utilising cutting-edge methods such as Multi-Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA)[1]. It is a precursor to cluster/sectoral needs assessments and provides a process for collecting and analysing information on affected people and their needs to inform strategic response planning. People First Impact Method (P-FIM) is another tool and an approach that gives communities a voice. It allows communities to identify the important changes in their lives and what these are attributable to, and reveals the wider dynamics within the life of a community.”

While sharing limitations and opportunities of applying quality & accountability, Fadi Kas Elias from Syria added, “In Syria, we have started to focus on the quality of humanitarian interventions since we are at the transition period of emergency to recovery. On the other side, we sometimes place far more emphasis on how to comply with donor requirements than on assuring the effectiveness of interventions. There need to be more coordination between humanitarian actors themselves at ground level to deliver quality assistance, share information and experiences and work together more effectively. Furthermore, we need to raise awareness within the communities we are working with about complaint response processes. Because communities are hesitant to provide feedback, we must encourage them to communicate their experiences and feedback about project interventions more freely and without fear. We can work to strengthen community capacity in areas such as safeguarding, early recovery of livelihoods, localisation, and so on, so that humanitarian actors can rely on them and maximise their influence.”

Diab J. from Syria shared some of the challenges and key actions with regards to complaint mechanisms, “Communities are hesitant when using the complaint response mechanisms. People fear that help will be cut off or that their safety would be jeopardised as a consequence of a lack of information. As a result, we need to ramp up our public awareness activities so that the CRM can be used productively. Furthermore, humanitarian organisations, particularly at the local level, must collaborate to overcome challenges and effectively serve community needs. To successfully meet the requirements of the communities, we need to strengthen our community mapping. Furthermore, service providers’ capacity building on various standards, such as the Core Humanitarian Standard, is critical in order to have a strong grasp of how to offer humanitarian relief while guaranteeing quality and accountability.”

ASKs for next session: How do we make it happen practically? What are the key actions we need to see functioning through the project or programme cycle?

It is imperative to review the adoption and use of Quality, Accountability and Safeguarding throughout the various phases of the Project/Programme Cycle Management. “The initial assessment and design must be prioritised since they will set the tone for the rest of the project cycle. We can connect the project cycle with the humanitarian programme cycle from the global coordination. It gives us an opportunity to advocate for humanitarian principles and guarantee coherence of standards’ application through the cycle phases,” shared Sylvie, in conclusion of this first Virtual Learning Session ‘LEARN’.

Way Forward

Participants have been asked to reflect and share their feedback on ‘How they do/would you apply Quality, Accountability and Safeguarding throughout the Project/Programme Cycle’ in their specific context’.

[1] The Multi-Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) is a joint needs assessment tool that can be used in sudden onset emergencies, including IASC System-Wide level 3 Emergency Responses (L3 Responses)