Archives

A School Reborn

Though Kumbhar Bhada lies only 45 kilometres east of Umerkot town, its setting among vast sand dunes gives it the feel of a remote desert settlement. Home to around a hundred families, all of whom are Muslim, the village has long struggled with limited educational facilities. Two government schools exist, one co-educational and another for boys, but opportunities for girls have remained scarce. In the early years of this century, the government allocated a single room to function as a girls’ school. For a community where families often have ten or more children, this provision was far from sufficient, leaving many girls without access to meaningful education.

No official teacher was appointed, however. In this vacuum, an NGO sent a woman teacher to work in the village. This private project lasted some five years and with its end the school closed down in 2007. Though some rare girl students joined the boys school, most simply dropped out and became their family’s help in household chores or in the fields. In a nutshell, since about 2007 there was no girls’ school in the village. For parents, themselves generally uneducated, this was no significant setback. Girls at home meant they could be gainfully employed with the parents to help at home and in the fields. However, there were also those rare parents who wanted their daughters to be educated.

In January 2024, community elders appealed to Community World Service Asia (CWSA) to revive the abandoned girls’ school and bring it back to life with a dedicated teacher. Responding to this call, CWSA appointed a qualified woman teacher and equipped the school with resources to make learning both meaningful and enjoyable. Children were introduced to sports equipment such as hoops and balls, and delighted in the novelty of a steel frame fitted with two swings. Classrooms were enriched with colourful teaching aids, foam blocks marked with alphabets and numbers, along with picture books, transforming lessons into engaging experiences.

Another highlight, under a sister project also implemented by CWSA, was the introduction of a school feeding programme, ensuring that every child received a nutritious lunch. The menu varied daily, with vegetables and lentils forming the staple, and chicken biryani served once a week, a meal that not only nourished but also brought joy to the students. This initiative helped safeguard children from malnutrition and encouraged regular school attendance.

As the single classroom could not accommodate cooking and serving, the community rallied together to expand the facilities. A hut was built beside the classroom to serve as a dining area, while a small shed became the cookhouse. The village community centre was also handed over to the school, repurposed as a pantry. These collective efforts created a welcoming environment where children could learn, play, and thrive.

Rather tentatively the attendance register listed some 35 students in the first week. Numbers slowly ticked upward and soon there were 80 until the rolls now stand at 120. As the students take their classes in the single room, two local women in the hut adjacent to it prepare lunch. During the break, the students take turns, 20 at a time, to be fed.

Gulshan, third among five sisters and seven brothers, is in Grade 2 and says she is eight years old. She started classes some years ago in the coeducation school, but soon dropped out. She has no idea if her parents thought it improper to her, a grown girl even at the age of eight, to be studying with boys, but she says she was put to work helping her mother with household chores. During the farming season, she went with her parents to their small holding where she minded her younger brother while the parents worked.

Though one of her older brothers takes local transport to Kaplor, six kilometres away, to attend school in Grade 5, none of her other sisters are in school. Some of her younger siblings do attend the local mosque for religious lessons, however. Quite clearly her family is not one that lays any great merit on girls’ education.

Gulshan has been in school since it restarted in January 2024 and in almost two years has worked her way to Grade 2. In between, her attendance became irregular and she relates that her parents would take her to work in the fields. Outside of farming season, when her father goes to work in a confectionery shop in Karachi, her mother insists she stays home to help with housework. She says she wanted to be in school and it was only after much pleading with the elders that she was able to resume classes. She affirms that she will continue to attend school even if the lunch programme comes to an end when the CWSA project ends in 2026. She has to fulfil her dream of being a doctor one day.

Eleven-year-old Ayaza, the third among three sisters and six brothers, carries a story marked by resilience. Living with a polio-affected leg that causes her to walk with a limp, she refuses to let this challenge define her. In fact, she considers herself fortunate compared to one of her brothers, who suffers from polio in both legs and can only crawl. When her parents are busy tending their small plot of land , where Ayaza also lends a hand, her father supplements the family’s income by working as a labourer on construction sites. For the family, however, education has never been a priority. Only one of her brothers attends the local boys’ school, leaving Ayaza and most of her siblings without access to formal learning.

When asked about her future, eleven-year-old Ayaza speaks with quiet conviction. After completing Grade 7, she dreams of becoming a teacher. Her heart is firmly set on this path, and she insists she will do whatever it takes to achieve it. For Ayaza, the daily school lunch is not the only motivation to attend classes; she carries with her higher ambitions and the hope of shaping young minds one day.

For Grade 2 students, both girls read surprisingly well from their primers. Even random pages are read fluently. This surely is a reflection on the efficiency of the teacher and her teaching methods.

In the two years since CWSA rehabilitated the school, a Children’s Day and a Cultural Day festivals have been held. Both events were fun-filled days of games and eats attended by students of the other two schools as well. According to the parents, despite the schools functioning since the mid-1990s, these events were the first such to have ever taken place in the village. It seems this might be the reason parental interest in their children’s education has risen and the students are not being withdrawn to help at home.

As the CWSA project draws to an end in late 2026, the school will be handed over to the government and a lady teacher appointed here. Going by the yearning for education seen among the students, it is clear that the village committee will raise a clamour in the event of government apathy. Surely children like Gulshan and Ayaza and all the others who dream of being useful adults need to be given the chance to prove themselves.

Upwardly mobile Ameenat Rind

In 2016, Nangar of Mallay ji Bhit died of tuberculosis of the lungs. In his final weeks, he was also haemorrhaging violently from the nose and mouth and had to be hospitalised in Karachi. In that trying time, Ameenat tended to her home and five daughters while her only son looked after the ailing father in the hospital. Ameenat says her husband’s hospitalisation cost the family about PKR 400,000 (approx. USD 1428).

She sold her two buffalos, one cow, three goats, a donkey and the cart to pay for the treatment. But when she was left with nothing more to sell, she borrowed from family and friends. Sadly, Nangar’s illness was so far gone that there was no coming back and when he passed away, Ameenat was under a debt of PKR 250,000 (approx. USD 893) and with no assets. She was lucky that her relatives wrote off their loans to her. There still remained a substantial sum owed to others. She and her eldest son eventually repaid after much hard work over three years during which she worked as a sharecropper, while her son tended other people’s livestock.

Ameenat’s most handy skill is mud plastering of houses for which she is called by householders in the village. As well as that, during season she goes chilli pepper or cotton picking which fetches PKR 500 (approx. USD 1.79) for every 40 kilograms picked.

Between 2021 and 2024, things were comparatively better for her and she wedded off her son and two of the older daughters. To complete the count, she says, she still has to wed three more girls. Now with her son working as a helper on a waste management truck for PKR 15,000 (approx. USD 54) a month, she was always worried it would take a long time to arrange the necessary dowry for the girls.

“My son gives me Rs 5000 to 7000 [approx. USD 18 to 25] a month from his salary. But that is only enough for household expenses, not to put away for dowry,” says Ameenat.

Her fortune changed when she became one of the participants under a food security and livelihoods initiative implemented by Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and financially supported by Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH). In October and November 2024, she received the first two installments of multi-purpose cash assistance under the project. That year, her portion as sharecropper was reasonable and the cash was used partially for food while the bulk was spent on dowry items. It was the goat that came with the package that was the biggest boon because it soon delivered a very healthy kid.

Ameenat says she would normally have worried about the health of her goat in the dry season starting in March, but in 2025, she had hydroponic fodder to augment the dry fodder she had saved from the past harvest. The kid gambolling around her yard looks very healthy and she says though it is now weaned, it had plenty of milk when it needed because of the green fodder she was trained to grow. The bonus was the supplemental feed for the goat which also increased its milk production and she was able to have her own supply for morning and evening tea.

The kitchen garden was another great bonus. Since the death of Nangar, the family rarely had vegetables to dine on but that was not the case now. This was only when her son came home for a day or two and brought a supply from town. In November 2025, she was preparing her little patch for the third round of gardening.

“We used to have homemade chilli and garlic chutney with chapatti [flatbread] because we could rarely afford vegetables. But now there is so much and in such variety that when vegetables are in season we always dine well and also give away to others,” says Ameenat. She is proud that she now entertains visitors with good milk tea and excellent vegetable stews.

“Since this intervention, our life has changed for the better. I can now look forward to buying my own livestock again. If luck holds out I will have at least one buffalo in good time,” says Ameenat.

Nourishing Futures with Sphere Standards

At Community World Service Asia, school meals go beyond filling plates; they nurture growth, learning, and well-being. As Sphere’s Regional Partner in Asia, we integrate Sphere food security and nutrition standards into our school feeding project, supported by PWS&D and CFGB, to ensure every child receives safe, balanced, and culturally appropriate meals.

Our approach focuses on:

- Assessing nutrition and food security to meet children’s real needs

- Preparing meals with locally sourced, balanced ingredients

- Upholding hygiene and food safety at every step

By combining care, local knowledge, and international standards, children are eating healthier, attending school more regularly, and thriving academically.

Because when meals are made with care, children learn better, grow stronger, and dream bigger.

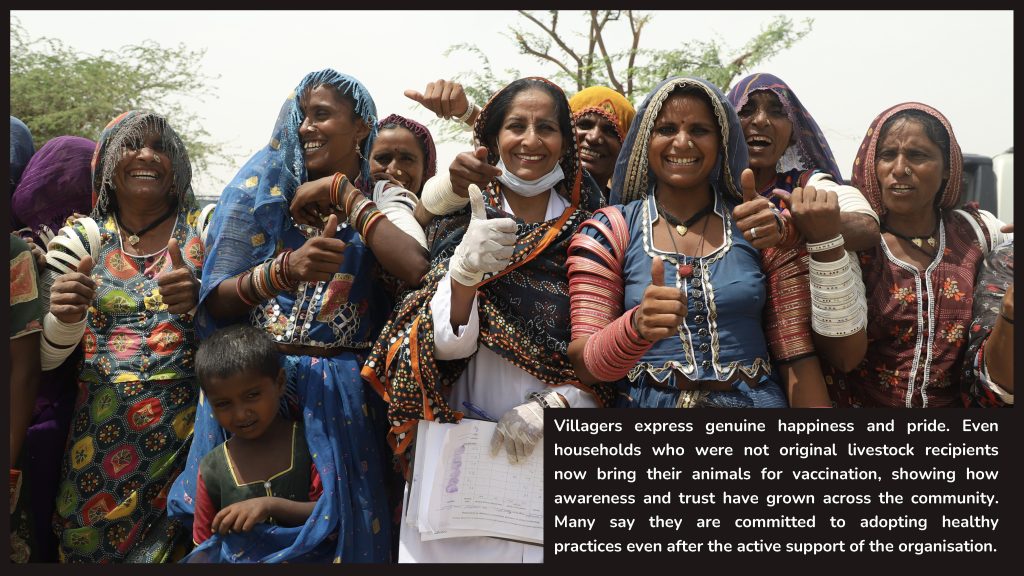

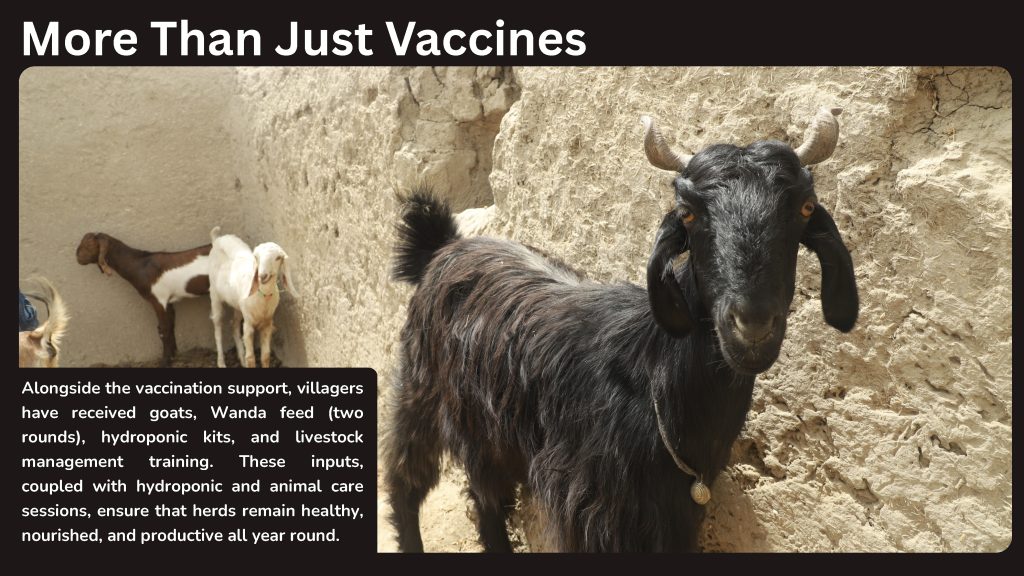

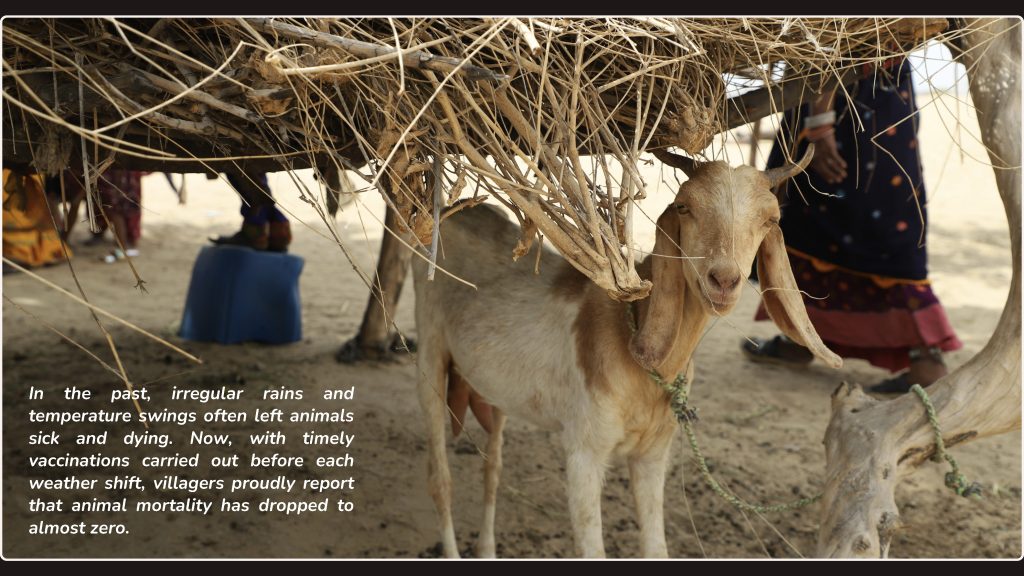

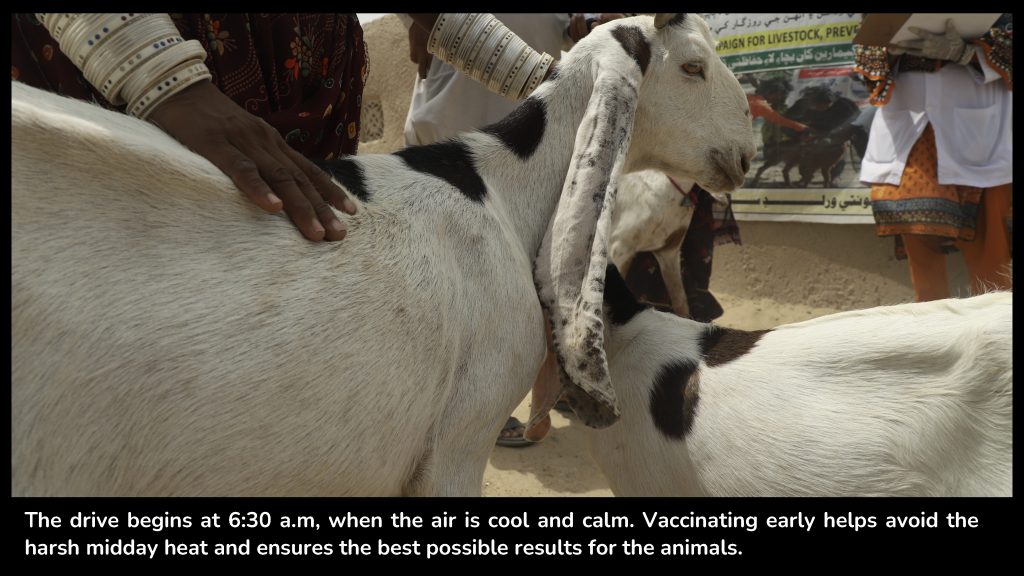

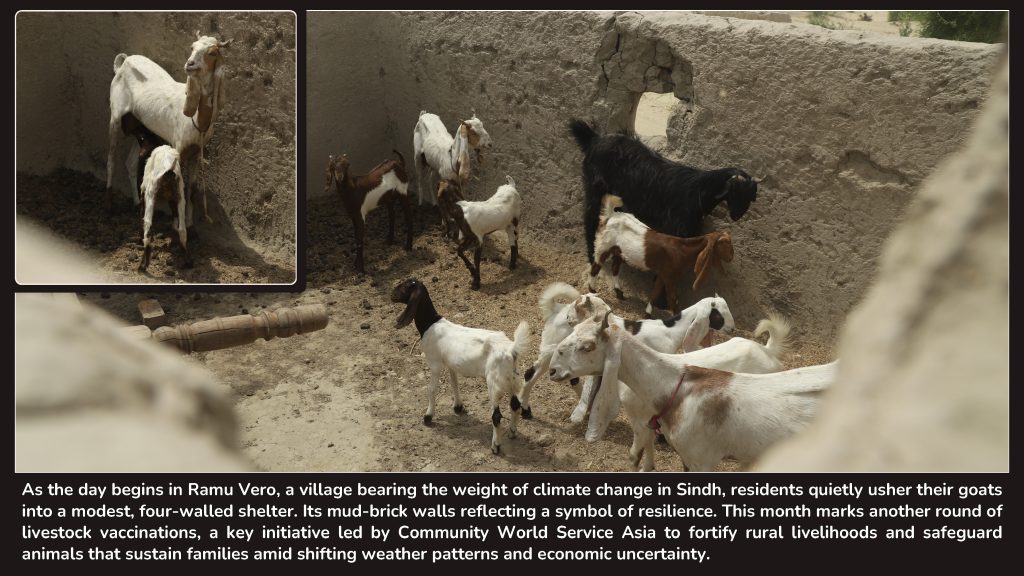

Livestock Assistance in Village Ramu Vero:A Healthier Herd, A Stronger Livelihood

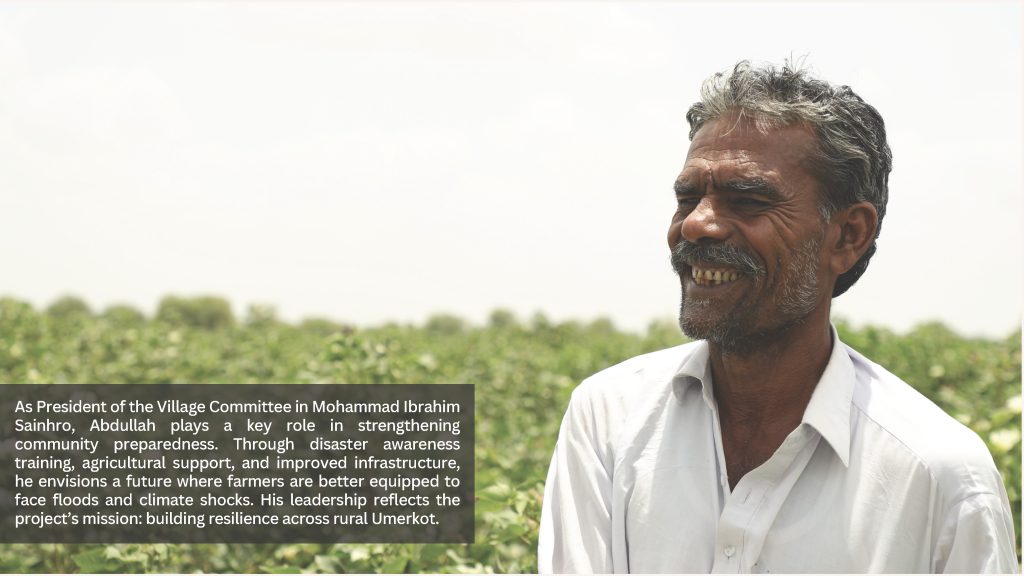

Prepared for Tomorrow: Empowering Thar’s Communities to Face Disasters with Strength and Unity

In the heart of Umarkot’s desert, communities are finding new strength through collective resilience. With support from Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH) and Community World Service Asia (CWSA), villagers across Tharparkar are learning to respond to disasters, protecting their homes, and leading with confidence. Through inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) trainings, purpose driven community structures, and women’s active participation, these communities are not only better prepared for emergencies but are reshaping social norms and standing resilient and ready for an uncertain future.

Building Community Resilience Through DRR Trainings

Where drought, extreme heat, and chronic water scarcity shape daily existence, the struggle for survival is relentless in Umarkot. Yet amid these harsh conditions, the community’s greatest strength lies in its solidarity; sharing land, food, and hardship with unwavering resolve.

For years, Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH) has been a steadfast catalyst for progress in these remote regions. In recognition of the acute shortage of essential resources, Community World Service Asia (CWSA), in collaboration with DKH, launched a wide-reaching initiative across 15 villages in Umerkot, positively impacting hundreds of households. This multifaceted program integrates in-kind support, cash assistance, and disaster preparedness to fortify livelihoods and nurture resilience in areas where both water and opportunities remain scarce.

Among the most transformative elements of this initiative is the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) component, designed to equip communities with the knowledge and tools to respond swiftly and collectively in times of crisis, without relying solely on external aid.

Across these villages, hundreds of men and women have embraced leadership roles, following comprehensive training and the provision of critical resources. Each village now hosts a dedicated Emergency Response Team (ERT) comprising 15 trained volunteers, organised into three specialised committees: the Information Committee, which issues early warnings; the Search and Rescue Committee, the first to respond when disaster strikes; and the First Aid Committee, which tends to the injured.

Gender inclusive participation has been a foundational principle of these efforts. Both men and women share responsibilities in the village management committees, promoting equitable representation while honouring cultural traditions. Although men slightly outnumber women in the DRR team due to the physical demands of certain roles, women remain integral to the process, leading awareness sessions, conducting risk mapping, and strengthening communication across communities.

These teams have undergone practical training on topics of first aid, rescue techniques, early warning systems, and risk mapping, reinforced by frequent mock drills to test their readiness. Through these sessions, communities are not only learning to respond to emergencies but to do so with confidence and unity.

CWSA conducted a comprehensive needs assessment to identify the most pressing threats across Thar’s arid landscape. While drought remains a persistent challenge, the survey revealed that snakebites and fires pose even more immediate and deadly risks. Residents of several villages recounted harrowing fire incidents that engulfed homes within minutes, leaving families devastated and vulnerable.

To address these hazards, DRR rooms were established in January of 2025, and outfitted with vital emergency tools including megaphones, ropes, axes, torches, shovels, boots, raincoats, fire jackets, helmets, sandbags, and buckets, ensuring rapid access during crises.

Yet the initiative extends far beyond the provision of equipment. At its core, It’s about cultivating knowledge, fostering coordination, and promoting accountability. Communities played an active role in electing DRR committee members and crafting preparedness plans tailored to their unique circumstances and everyday their realities. This participatory approach ensures sustainability and strengthens local ownership of the process.

In Veeharo Bheel and neighbouring villages, a recurring tragedy underscored the urgency of localised solutions; the heartbreaking loss of children who drowned after falling into unsecured water tanks. Rather than relying on commercially available lids that deteriorate over time, villagers, supported by the project’s guidance, constructed durable covers using locally sourced materials. This practical innovation not only addressed an immediate safety concern but also ensured the sustainability of maintaining the solution for years to come.

“Something as basic as a megaphone comes to our aid when an accident occurs and word needs to get out,” shared one villager, reflecting on how small tools now play life-saving roles.

Among those inspiring individuals driving change in Umarkot is Hakeema Begum, a dedicated volunteer from Dayitrio village and mother of six. Hakeema plays a pivotal role in raising awareness, coordinating emergency response, and ensuring that no household is left behind during times of crises. “I want my children to grow up in a safer environment, to learn, to thrive, and to give back to their community,” she says. While deeply appreciative of this initiative, Hakeema continues to advocate for a more comprehensive training, particularly in firefighting and first aid, underscoring the critical importance of these skills in Thar’s unforgiving remote and terrain.

Beyond enhancing preparedness, the project has quietly transformed social norms. Women, who once seldom ventured outside without male accompaniment, are now active agents in community development. “Before, women couldn’t leave the house without a man,” one villager reflected. “Now they go to markets, attend meetings, and take part in trainings on their own.”

This shift is celebrated across the community. Sohdi, a member of the Village Management Committee and a DRR leader, expressed her pride.

“There’s no thought of women being confined to their homes anymore. We work, we travel, and we support each other. It has changed the fabric of our community.”

Through inclusive learning, shared leadership and collective action, the efforts of DKH and CWSA have extended far beyond immediate relief. They have restored confidence, renewed dignity, and fortified resilience, ensuring that these desert communities are not merely enduring their environment, but are equipped and empowered to shape a safer future.

A short walk to clean water

Advancing Climate Leadership and Strategic Action: CWSA Hosts Two Transformative Events in Sindh

Two events in September, co-hosted by Community World Service Asia (CWSA), held in Karachi and Hyderabad, brought together educators, civil society organisations (CSOs), development professionals, and public and private sector representatives to address climate-related challenges and strengthen institutional capacity in Sindh.

Empowering Educators to Lead Climate Action in Karachi

On September 30, 2025, CWSA partnered with the Teachers’ Resource Centre (TRC) to host a one-day event titled “Empowering Educators to Lead Climate Action for a Sustainable Future” at the TRC campus in Karachi. The gathering brought together a diverse audience of teachers, coordinators, education officers from public and private schools, and representatives from the corporate, finance sector and other organisations.

The event opened with a keynote address by Ambreena Ahmed, Director of TRC, who emphasised the critical role educators play in advancing climate action aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 13.

A lively panel discussion followed, featuring climate activist Afia Salam, development expert Naveed Ahmed Shaikh, gender justice and localisation advocate Plawashay Arbab, environmental entrepreneur Ahmed Shabbar, incubation head Raza Abbas, and youth leader Rizwan Jaffar. Together, they explored climate education, Karachi’s environmental challenges, and innovative solutions for climate-responsive learning.

The panel discussion focused on how climate awareness must evolve as a ground-up movement, beginning from schools. Speakers stressed the importance of empowering school administrators with the authority to implement tangible measures, reflecting the kind of responsibility often reserved for government bodies. The discussion emphasized the need to educate and engage the most receptive segment of society, the youth, the generation soon to take the lead and bear the brunt of it.

Climate Activist Afia Salam shared, “Climate change should not merely pertain to ecological areas, or be limited to geography or environmental lessons, but should be prioritised across every facet of schooling, as all are equally affected, be it physical activity, design thinking, or critical analysis. A country like Pakistan has faced massive flooding catastrophes in its history, the most devastating being in 2022, when more than half of Pakistan was submerged. Now you tell me, how many children know swimming as a basic life skill?”

Afia left the audience with a reflective question, it is not a one-time lecture to be discussed casually during free periods; rather, it is a responsibility that every teacher owes to their students, to convey the weight and urgency of the issue.

Ahmad Shabbar, leading a waste recycling organisation, shed light on how small individual efforts can collectively lead to significant change. He shared a short story about receiving thousands of books and papers meant to be recycled. Instead of discarding them, his team distributed them among underserved children who had little access to water, let alone books. He also recounted how, after floods destroyed several schools, they built small libraries out of recycled bottles, wrappers, and plastics, structures just as strong as concrete ones.

He attributed much of the environmental gap and disparity to a growing disconnect, a disconnect from nature, from the environment, and from one’s surroundings.

Raza Abbas, the Incubation head at the renowned Institute of Business Management, reiterated an emerging phenomenon: climate-tech startups. He reflected on the broader state of Pakistan and its people. How, over time, systemic inefficiencies have alienated many from observing civic discipline, whether in traffic regulations or adherence to policies. Years of frustration with governance and societal systems, he noted, have led to disengagement and apathy toward issues like climate change.

“But the thing is,” he emphasised, “both go hand in hand, and we must focus on leaving the world better than it was before.” He further highlighted the significance of teacher participation, noting that youth remain the most affected population when it comes to climate change and should be the ones most prepared.

Strengthening Strategic Planning for Climate CSOs in Hyderabad

In Hyderabad, CWSA joined hands with the Global Network of Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction (GNDR) to co-host a one-day learning event titled “Funding & Developing Strategy for Climate CSOs in Sindh” at the CSOs Club. The event convened CSO leaders, parliamentarians, academics, and representatives from the public, private, and corporate sectors to discuss strategic planning, resource mobilisation, and institutional sustainability.

Advocate Saima Agha, MPA and Chairperson of the Standing Committee on Sports and Youth Affairs, Government of Sindh, addressed the closing session, highlighting the shrinking civic space and the need for policy and legal support to enable CSOs to fulfill their development roles effectively.

The event featured thematic presentations by experts including Khadim Dahot (SEWA Trust), Danish Batool (CWSA), and Kashif Siddiqui (CARD), who shared insights on funding landscapes, locally led initiatives, and strategic planning. A panel discussion moderated by Amarta included voices from BASIC Development Foundation and the Social Welfare Department of Sindh.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) was also a key focus, with contributions from Abid Ali Gaho (OGDCL), Asim Ahmed (Askari Bank), and Ghulam Abbas Khoso (GEF CSOs Network), who discussed the private sector’s role in supporting social development through CSOs.

Tahira Joyo, who moderated the event, summarised key reflections and emphasized the importance of strategic planning in adapting to climate challenges and evolving development needs.

Several participants shared their reflections on inclusion, participation, and accountability within climate strategies. One attendee noted: “Our climate strategies will remain incomplete until we actively bring women to the planning table. At the local level, women are not just victims of climate change, they are custodians of knowledge on water, food, and energy. A truly resilient Sindh requires funding and programs that are designed with women, not just for them. When our plans are gender-inclusive, our communities become climate-proof.”

Another attendee representing a local climate advocacy group added a perspective of youth: “While we demand larger systemic change, we cannot overlook the power of our individual actions. Every plastic bottle we refuse, every tap we close, and every native plant we grow is a vote for the future we want to see. Responsibility doesn’t start with governments or corporations alone, it starts in our homes, our universities, and our local communities. We, the youth, are not just leaders of tomorrow; we are the accountable citizens of today.”

A Shared Commitment to Climate Resilience

Through these two events, Community World Service Asia reaffirmed its commitment to fostering inclusive dialogue, capacity enhancement, and collaborative action for climate resilience. By empowering educators and strengthening CSOs, we are helping shape a more sustainable and responsive future for communities across Sindh.

Situation Report V: Floods 2025: A Humanitarian Emergency Demanding Urgent Action

Pakistan is facing one of the most catastrophic monsoon flood emergencies in recent history. Torrential rains, compounded by cross-border water releases from India, have triggered widespread riverine overflows across Punjab, while northern regions remain highly vulnerable to flash floods and landslides. As of mid-September, over 3 million people had been evacuated, with 150,000 still sheltering in evacuation centres. Though waters in Punjab have begun to recede, the scale of devastation is staggering.

More than 2.6 million displaced people have returned to homes that are damaged or destroyed. The Punjab Disaster Management Authority reports the loss of 2.5 million acres of farmland; severely impacting wheat and cotton harvests and threatening long-term food security. Urban flooding in Karachi has compounded risks, while stagnant water in rural Punjab and Sindh is fueling outbreaks of water- and vector-borne diseases.

Forecasts warn of continued heavy rainfall and rising river levels in the Sutlej, Ravi, and Chenab. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has flagged heightened risks downstream, particularly in low-lying areas of Sindh. As floodwaters shift southward, the humanitarian situation remains dynamic and demands sustained, coordinated response.

National Humanitarian Needs

- Shelter & NFIs: Over 2.6 million returnees in Punjab require emergency tents, repair kits, and winterization materials.

- WASH: Safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, hygiene kits, and disease prevention measures are urgently needed.

- Health: Mobile health services, essential medicines, and disease surveillance are critical to address rising cases of diarrhea, malaria, and dengue.

- Food Security & Livelihoods: Crop and livestock losses threaten food access and recovery, particularly in Punjab.

- Protection: Displaced women and children face heightened risks of exploitation and gender-based violence. Prolonged school closures are worsening child protection concerns.

The Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) has highlighted the urgent need to strengthen inclusive early warning and early action systems, backed by transformative investment in disaster risk reduction (DRR) to break Pakistan’s recurring cycle of flood-related loss and damage. Priority areas include:

- Community-based DRR; training local residents in search and rescue

- Forming Emergency response teams

- Building local capacity for immediate medical and psychosocial support

- Advancing locally-led climate adaptation requires complementing community knowledge with scientific and technical support to effectively address evolving risks.

Sindh Overview

Sindh province continues to be severely impacted, with intense urban flooding reported in Karachi, Hyderabad, and Mirpurkhas. The overflow of the Indus River has displaced approximately 191,500 people across 643 villages in 12 districts. Vulnerable communities residing in katcha1 areas have suffered extensive livelihood losses and significant damage to agricultural assets. Although conditions in Umerkot have now stabilized, the district endured widespread flooding throughout August and September.

| Humanitarian Needs in Sindh | |

| Health | Mobile health teams and essential medicines |

| WASH | Safe water, latrines, hygiene kits |

| Shelter/NFIs | Tents, tarpaulins, mosquito nets |

| Food Security | Dry rations and cooked meals |

| Livelihoods: | Support to restore income-generating activities |

| Protection/MHPSS | Psychosocial support and community outreach |

Gilgit-Baltistan Overview

In September, Gilgit-Baltistan was struck by Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) and flash floods, resulting in 41 deaths, 52 injuries, and the destruction of 1,253 homes. Infrastructure damage includes 87 bridges and 20 km of roads, with valleys such as Diamer and Ghizer cut off from relief access. Damages are estimated at PKR 20 billion.

| Humanitarian Needs in Gilgit-Baltistan |

| Shelter, clean water, food, and medical care |

| Winterisation support for displaced families |

| Strengthened health services to address disease outbreaks |

| Livelihood recovery and protection for vulnerable groups |

Community World Service Asia’s Response

Anticipatory Action in Sindh: With upstream river discharges threatening a “super flood” in Sindh, Community World Service Asia (CWSA) has activated anticipatory measures across flood-prone districts:

- Pre-positioned supplies: Lifesaving medicines, medical equipment, and hygiene kits stocked at Umerkot warehouse.

- Mobile health units: Strategically placed for rapid deployment.

- Risk communication: Disseminating early warnings, safe water guidance, evacuation protocols, and disease prevention messages in local languages.

- Coordination: Working closely with PDMA Sindh, health agencies, and cluster partners to ensure targeted, inclusive response and avoid duplication.

Additional support will be needed for winterisation, sanitation, shelter, logistics, and multipurpose cash assistance.

In Gilgit-Baltistan: In response to glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) and monsoon-induced landslides, Community World Service Asia (CWSA) has initiated emergency relief operations in Hunza and neighboring districts. Emergency Relief Kits have been distributed in Hunza, with preparations underway for the delivery of food supplies, non-food items (NFIs), and winterisation kits.

In Ghizer district, CWSA has established a dedicated field office, secured the necessary No Objection Certificate (NOC), recruited and oriented staff, and arranged two vehicles to facilitate field activities. Coordination meetings have been held with key stakeholders, including GBDMA, WWF-Pakistan, the Social Welfare Department, AKRSP, and the Deputy and Assistant Commissioners of Ghizer. Engagements with community organisations in flood-affected areas have also been completed.

Assessments for 240 project participants have been finalised, and data entry is currently in progress. Procurement processes have commenced following the submission of Purchase Request Forms (PRFs) and quotations for food packages. Distributions of food and multipurpose cash assistance are scheduled for October 2025.

Projected Gaps:

- Many households remain unreached due to access and resource constraints.

- Additional winterisation, sanitation, and shelter supplies are needed.

- Multipurpose cash support is critical where markets remain functional.

- Enhanced coordination with local authorities is required to facilitate last-mile delivery.

Coordination & Accountability

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) continues to work in close coordination with NDMA, PDMAs, UN agencies, humanitarian clusters, and ACT members in the country to harmonise response efforts and avoid duplication. As Co-Chair of the AAP (Accountability to Affected People) Working Group in Pakistan, CWSA places communities at the centre of the response by ensuring fair access to aid, clear and timely information in local languages, and inclusive decision-making processes and update the coordination networks accordingly. Safe, confidential feedback and complaints channels, through hotlines, community focal points, and helpdesks, are available across Sindh, Punjab, and Gilgit-Baltistan, enabling people to voice concerns and shape the response. Special efforts are made to reach women, children, persons with disabilities, and minority groups, while disaggregated data helps track who is reached and address risks of exclusion. Communities are also informed about the type, quantity, and timing of assistance, strengthening transparency and trust. These accountability measures are not add-ons but an integral part of CWSA’s principled humanitarian action, ensuring that relief is both effective and dignified.

Urgent Funding Priorities:

- Expand anticipatory action in Sindh with rapid deployment capacity and community communication.

- Scale up winterisation, shelter, and cash support in Gilgit-Baltistan based on community-identified needs.

- Strengthen logistics and last-mile transport to reach high-risk, remote communities.

Community World Service Asia remains committed to delivering principled, inclusive, and locally led humanitarian assistance. As the situation evolves, we call on partners, donors, and humanitarian actors to join us in scaling up coordinated response efforts and investing in long-term resilience across Pakistan.

Contacts:

Shama Mall

Deputy Regional Director

Programs & Organisational Development

Email: shama.mall@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Palwashay Arbab

Head of Communication

Email: palwashay.arbab@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

References

- UNOCHA Flash Update #10, 19 Sept 2025

- PDMA Punjab Situation Reports

- NDMA National Updates

- ADRRN Regional Advisory, Sept 2025

- PDMA Sindh Flood Update, Sept 2025

- District Administration Umerkot Updates, Sept 2025

- GB Government & NDMA Situation Updates, Sept 2025

- Pakistan Red Crescent Reports, Sept 2025

- Informal settlements ↩︎

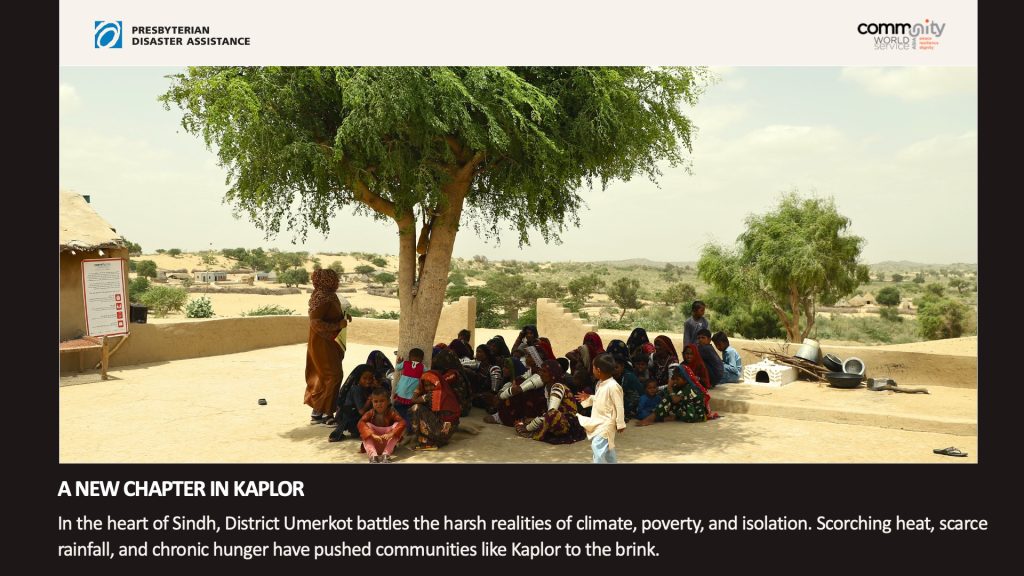

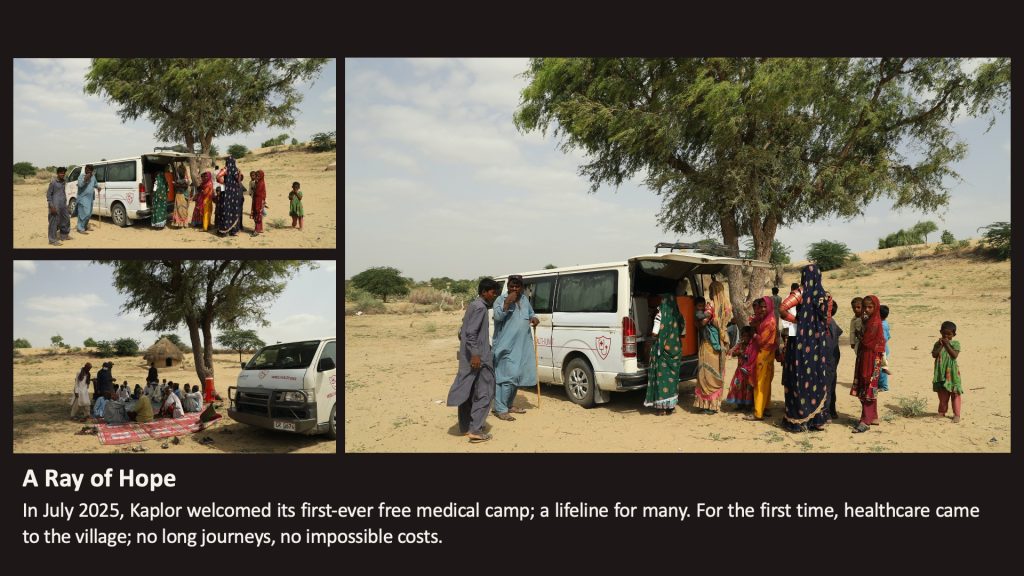

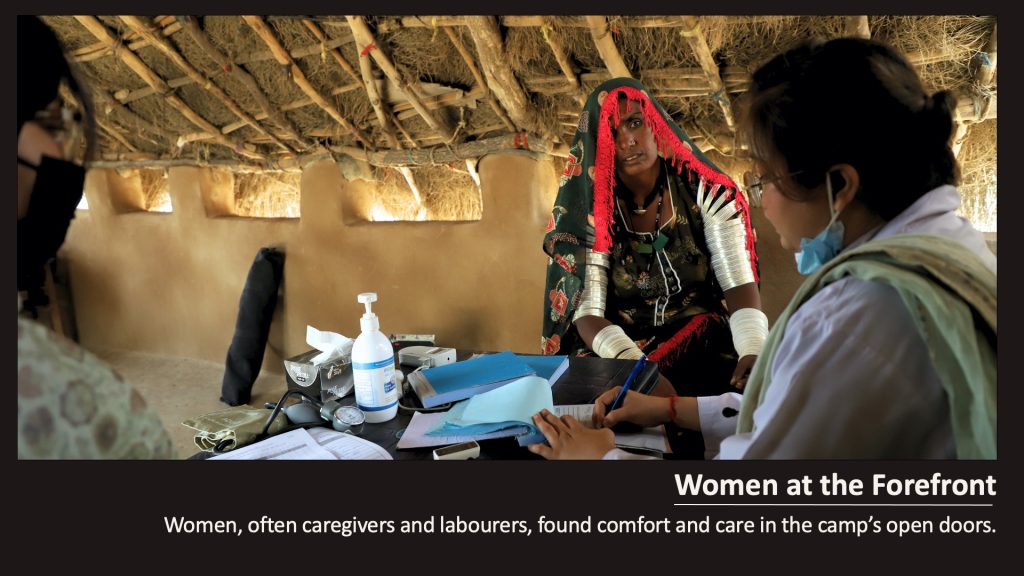

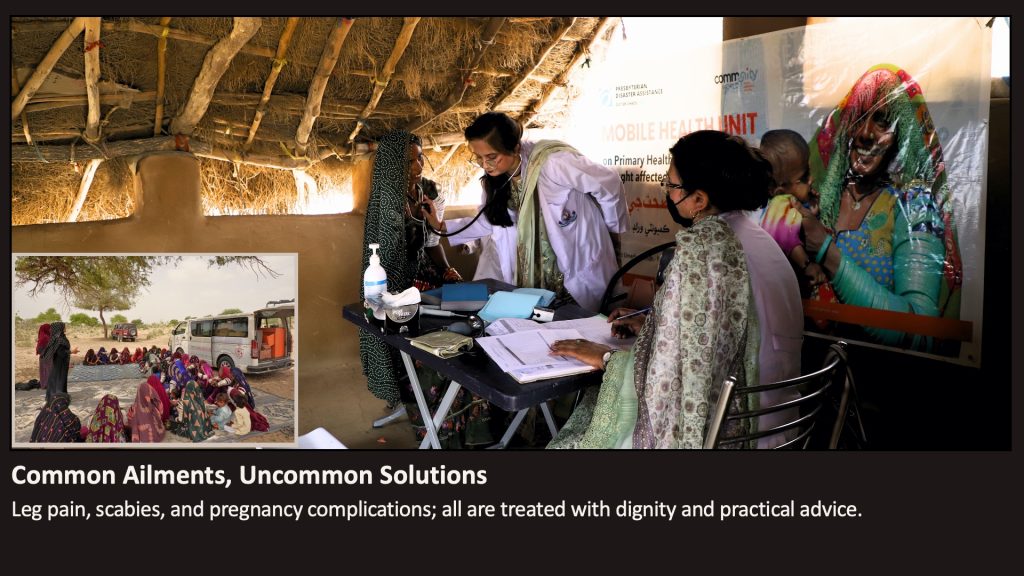

A new chapter in Kaplor