Archives

Scorching Surge: Sindh and Punjab on High Alert as Heatwave Temperatures Soar

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) on Thursday warned that extreme heatwave conditions would persist across parts of Sindh and Punjab in June, with temperatures likely to remain above 48 degrees Celsius.

The authority’s National Emergency Operations Centre said that Umerkot, Tharparkar, Tando Ala Yar, Matiari and Sanghar districts in Sindh are expected to be affected, while in Punjab, Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalpur are most likely to experience heatwave conditions.

In its advisory, NDMA also said that from May 31 to June 5, dust storms, gusty winds and light rain are also likely to occur in the upper regions of the country.

Extreme Weather Conditions

On Thursday, harsh weather conditions persisted across the Sindh province, even though temperatures dropped in most cities.

The Met Office recorded the maximum temperature in Jacobabad at 50.5°C, followed by Dadu at 49°C . Except for Karachi, which barely missed the mark with a high of 39.5°C and 63 per cent humidity, all other cities in the province registered temperatures above the 40 degree-mark.

Severe heatwave conditions persist across most parts of the province with daytime maximum temperature being 6-8 degrees above normal in Dadu, Kambar Shahdadkot, Larkana, Jacobabad, Shikarpur, Kashmore, Ghotki, Sukkur, Khairpur, Naushahro Feroze, Shaheed Benazirabad districts and 5-7 degrees above normal in Sanghar, Hyderabad, Mitiari, Tando Allah Yar, Tando Mohammad Khan, Mirpur Khas, Umerkot, Tharparkar and Badin districts.

The heatwave conditions are likely to persist till June 1st.

Warning the authorities to remain alert and take necessary measures, the NDMA advisory urged citizens to stay hydrated, avoid outdoor activities between 11am and 3pm.

Many labourers from remote areas travel daily to cities for work, but the current heatwave has severely disrupted their livelihoods pattern and led to worsening health conditions. The extreme heat makes commuting difficult.

The heatwave has also impacted people staying at home, as inconsistent electricity and lack of cooling options limit their ability to cope with prolonged heat stress. The ongoing hot and dry weather is stressing water reservoirs, crops, vegetables, and orchards, while also increasing energy and water demand, which is difficult to manage during the current crisis.

Community World Service Asia’s Response:

Community World Service Asia (CWSA), in collaboration with district authorities, has established a heatstroke centre/camp at the District Headquarters (DHQ) Hospital in Umerkot. The CWSA team initially launched their services by providing cold drinking water, conducting awareness sessions, and referring heatstroke patients to the DHQ. These awareness sessions are delivered directly to pedestrians, patients, and their attendants, messages to prevent heat strokes and raise awareness on precautionary measures are also broadcasted over speakers for public awareness. Every day, more than 1,000 people visit the centre to quench their thirst, as there is no fresh water facility available nearby to them. People not only come to drink water but also carry some back for family members or relatives who are hospitalised at the DHQ. So far, 20 critical patients have been referred to the emergency department after receiving initial treatment.

The CWSA health team has set up heatstroke corners at each public dispensary operated by CWSA to manage emergency cases and serve patients visiting from nearby villages seeking urgent medical services in the extreme heat. The team provides cold drinking water, first aid, ORS, and glucose sachets to visitors seeking medical care.

With additional support, CWSA also plans to establish three heatwave facilitation centres for three months in Umerkot district which will offer clean, cold drinking water, juice and shaded rest areas. Each centre will have generators, pedestal fans, stretchers, necessary furniture, basic medical equipment, and medicines. Two Lady Health Visitors (LHVs) and two medical technicians will rotate among the centres. The paramedic staff will perform emergency procedures such as checking blood pressure, administering medications, clearing airways, and initiating IVs if necessary. They will also apply cold bandages or towels to reduce body temperature. Critical patients will be referred to the nearest healthcare facility, with transportation provided.

These centres will also distribute informational, educational, and communication (IEC) materials to raise awareness about heat-related illnesses. The centres will operate throughout the peak summer months until the end of August.

Contacts:

Shama Mall

Deputy Regional Director

Programs & Organisational Development

Email: shama.mall@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Palwashay Arbab

Head of Communication

Email: palwashay.arbab@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Sources:

Relief Web

NDMA

Pakistan Metrological department

Dawn

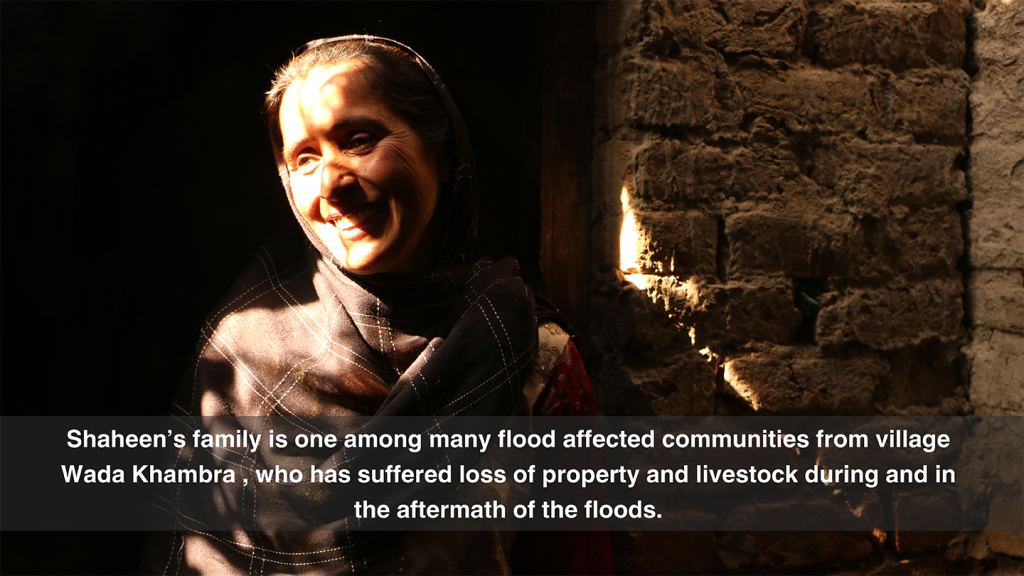

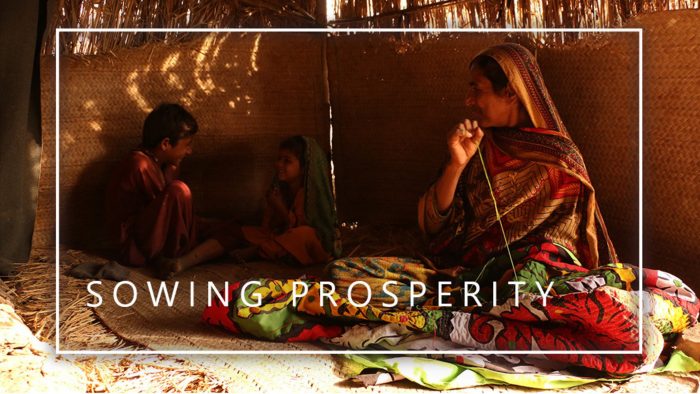

The Rebirth of Shaheen & her family’s Harvest

Pakistan to face three heatwave spells in May and June

Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has issued a heatwave alert for most parts of the country, especially for Punjab and Sindh provinces.

“It is forecasted that heatwave conditions are likely to develop over most parts of the country, especially Punjab and Sindh from May 21 and likely to advance into severe heatwave conditions from May 23 to May 27,” announced NDMA on Thursday.

The forecast delineates three separate heat wave spells. The initial spell is expected to persist for two to three days, followed by a subsequent spell lasting four to five days towards the end of May. Temperatures are anticipated to further escalate up to 45 degrees Celsius in June. The NDMA spokesperson has cautioned about the likelihood of a third heatwave spell in the initial ten days of the month, which could last for 3 to 5 days.

The NDMA underscores that heat waves will impact both human and animal populations, necessitating proactive measures before the onset of the anticipated heatwaves nationwide.

During the second heatwave, which is anticipated to persist for four to five days, the impact is expected to be felt particularly in Tharparkar, Umerkot, Sanghar, Badin, and Khairpur districts of Sindh.

Reflecting on past experiences, Pakistan encountered its worst heatwave in 2022, as highlighted in the 2022 report by Amnesty International. The report underscores the lethal repercussions of extreme heat, especially for more vulnerable communities and populations such as children, the elderly, individuals with disabilities, and those with chronic diseases.

Heatwaves exacerbate health conditions, leading to heat strokes, cramps, and aggravating pre-existing health issues such as diabetes, ultimately culminating in fatalities or accelerated deterioration of health.

Warnings have been issued by the provincial and district governments in Sindh, Punjab and KPK provinces of extreme weather in coming days and have advised people to take precautionary measures such as drinking plenty of water and avoiding direct exposure to the sun. The government is seeking assistance from humanitarian organisations in establishing heatwave camps/centres where affected people may find shelter and cold water, as well as receive basic first-aid treatment.

Community World Service Asia’s Response:

Community World Service Asia (CWSA), in partnership with district authorities, plans to establish four heatwave centres or camps in Umerkot district. These include one central site in Umerkot city and three additional camps near health facilities already supported via CWSA projects: Government dispensary Ramsar, Government Dispensary Jhamrari, and Government Dispensary Cheelband. These camps aim to offer basic services such as first aid, shelter, seating, clean drinking water, and juices to vulnerable individuals in the area, including pedestrians exposed to the sun and at risk of dehydration. With the expected rise in heatwave occurrences, CWSA will plan to expand its efforts to provide similar assistance, as well as first-aid treatment and public awareness campaigns in areas where it maintains operational presence.

Contacts:

Shama Mall

Deputy Regional Director

Programs & Organisational Development

Email: shama.mall@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Palwashay Arbab

Head of Communication

Email: palwashay.arbab@communityworldservice.asia

Tele: 92-21-34390541-4

Sources:

Relief Web

NDMA

Pakistan Metrological department

The Nation Newspaper

The Dawn Newspaper

Greener Pastures: The Awakening of Umeed Ali Chandio’s farmers

Lal Ji, his wife and three children of village Umeed Ali Chandio just outside Nabisar (Umerkot district) live in a very neat, well-kept, almost picturesque home. He is a landless farmer who works eight acres of a landlord’s holding and shares the proceeds with the owner. But he blindly followed farming procedures unchanged for centuries. He cites the example of how millets, guar and mauth lentils were sowed all together in the same plots despite each having a different ripening time.

“When the first crop was ready and we harvested, we damaged nearly half of the remaining unripe species underfoot and with the sickle. That was the way passed down to us by our elders and it simply did not occur to us that planting each specie in separate plots could double the yield of those ripening later. It had to be the staff and trainers of this organisation (Community World Service Asia (CWSA)) to teach us how to do the right thing under!” says Lal Ji.

Asked why it was like that and why he or other farmers did not think logically to increase their yield, Lal Ji simply shrugs and says that was the way of the elders. “But now we are awakened and I am myself surprised how such a simple thing eluded us,” he adds.

If that ancient practice put Thar farmers at a disadvantage, the periodic disasters added to the deterrent. In 2021, Thar was invaded by a pestilence of locust. That year Lal Ji had invested PKR 40,000 (Approx. USD 143) in the eight acres he was farming. This sum had all been borrowed from the landlord and when the locusts wiped out every last bit of green from his fields. He went under debt and had to live by selling off some of his livestock. The year that followed was hardly any better. If there was no locust, the summer rains failed and once again Lal Ji kept body and soul together by disposing off some more of his livestock.

The beginning of 2022 brought in succour. The multi-purpose cash grant, agricultural and vegetable seeds together with training under CWSA & DKH’s food security and livelihood support, smoothed the bumpy road Lal Ji was treading. His excitement about learning to plant millets, guar and mauth in different plots is still viable two years after learning this evident truth. The cash grant helped him pay off his debt and the year when the rest of Sindh was drowned out by the worst deluge known in living memory, his fields in the troughs of the dunes did well with the natural irrigation.

In December 2023, he recounted how he had harvested 400 kilograms each of millets, guar beans and mauth. The millets he kept for his family while the rest he sold. However, being the judicious man that he is, Lal Ji retained enough seeds for his 2024 summer plantation.

Another thing that Lal Ji and the others learned in the training was that selling the harvest wholesale fetched better prices. Earlier they would be approached by the bania (Indian caste consisting generally of moneylenders or merchants) from town who would offer the farmers a price for the standing crop. Since these poor farmers did not have the means to truck their harvest to the market, they reluctantly accepted the offer even when they knew it was fifty percent below the market price. Those who did not, would harvest and pack 40-kilogram sacks to haul to market by donkey as and when they required cash. Though they got marginally more per kilogram than selling the standing crop, the price was still below the market rate.

The training taught them to work cooperatively. In late 2022, when the separately planted crops were nearing harvest, the bania arrived with his offer only to be disappointed. He was told that this time the farmers were to bring their goods to him. And so, Lal Ji and five others filled up their sacks, hired a pick-up truck and hauled the harvest to the market where they sought the best buyer. The profit astonished the group. Once again Lal Ji is amazed why they had not thought of this simple mechanism by themselves.

It takes motivation, a bit of awareness raising and the freedom from worry for communities to think of the future. Following the first CWSA intervention, the village organisation repeatedly beset the District Education Officer and got a regular teacher for the village school who, they insisted, must be a local person and not from another district. This was to ensure interest and regular presence. The teacher, a Nabisar young man, now attends school daily.

Meanwhile, Lal Ji sends his two sons and daughter to the school in Nabisar town. They walk the three kilometres to and fro. For pre-teenage children that’s a tough walk through the sand, but Lal Ji says that the produce of the kitchen garden has added so much vigour to their lives for the children to even be tired when they return in the afternoon. “They also take PKR 20 each for something to eat from their school tuck shop,” says the man.

Sixty rupees daily sounds expensive and Lal Ji says he had always given his children this daily allowance. In days of adversity, he borrowed the sum from the village shop keeper. Now he gives it out from his own purse.

Almost breathless in his narration Lal Ji moves on to the boon of hydroponic agriculture. It is the greatest discovery in Lal Ji’s vocabulary. He shows off his trays of young maize seedlings and narrates how he has already fed one round of this miracle to his three goats even as the second is ready for cutting. The two goats that are in milk have markedly increased yield and his wife is able to give the three children half a glass each with breakfast.

A few houses away, young Bilawal is a livestock keeper with thirty goats who had long supplied the village with dairy products. He too has hydroponic trays in a shed for his livestock and has already fed his livestock three rounds from them. He says his four trays are too few for his stock and plans to increase them to twelve.

“Earlier I got not more than 250 ml of milk a day from each goat. This hydroponic feed is always available, even in the driest part of summer. And now my goats yield twice as much milk,” recounts Bilawal. From the five to six litres of milk from ten lactating goats he produces yogurt and clarified butter (ghee). While the yogurt is used at home, the ghee is a cash produce.

Bilawal says that livestock feed was always a problem during the drier months of summer. As a result, milk output almost dried up during those times. But since he has discovered hydroponic gardening, his goats are yielding very well. If things go well, Bilawal hopes to add a couple of buffaloes to his stock before the end of 2024.

It seems the livestock farmers of village Umeed Ali Chandio have hit the lode.

Threading Progress

In a straight line, Old Subhani lies 30 kilometres due east of Umerkot town; it is a tad longer by the tarmac road. Here Jagisa is a member of the Advisory Committee established in October 2022 after the Community World Service Asia’s training sessions under the HERD project. She says she did not miss a single session. Jagisa is the kind of person who needs no prompting to speak and is quick to relate how being a part of the embroidery makers of Taanka she learned at least one new stitch she had never known before.

“Hurmuchi is a stitch that adds so much value to our work. Earlier we were doing straightforward applique rallis. Now there is greater variety in our products,” says Jagisa. “Just a year before the training a typical ralli bedspread would sell for no more than PKR 800 (Approx. USD 2.8) in the village. It would fetch the same price in Umerkot.”

Now a ralli of the same size fetches PKR 1500 (Approx. USD 5.3) in the village. The better design has greater demand in Umerkot where their menfolk sell them. And if the men only knew the art of haggling, they could get a couple of hundred rupees more. The Taanka group in Old Subhani is also turning out traditional Sindhi embroidered caps. Jagisa relates that the contractor supplies them the raw material and pays labour at PKR 1000 per cap (Approx. USD 3.5). Normally, it would take any woman fifteen to twenty days to turn out one of the more intricately patterned cap. A simpler one takes under ten days. However, if they get their own material, Jagisa says their profit would be in the range of PKR 800 (Approx. USD 6.3).

Kasuba, also a member of the Taanka group, points out that this new stitch being unknown in their village before the training, is now practiced by every applique maker. She says there were several young women who had not joined the training sessions and she has taken it upon herself to teach hurmuchi to all those women and even much younger girls.

Speaking of the drought of 2021, Lakhma, a member of the Resolution Committee, says it was a sort of blessing in disguise for the village. In such a situation in the past, leaving a man or two in each para (precinct) of the village, the community would migrate to the irrigated districts west of Umerkot. “First off, we got monthly rations for six months from CWSA which obviated the need to migrate. That meant our children who would be pulled out of school continued their education. Then we also got two goats per household and that was all the more reason to stay put,” she says.

Lakhma points out how the long trek to the irrigated area sometimes killed off their livestock. But for some years now, they no longer walk as it was before the web of tarmac was laid across the desert. Now they can get on the taxis that zoom around the desert. But living away from home was never free of insecurity and discomfort. There they had to build their temporary shelters of bamboo and wattle, usually open on one side and without a door leaving no room for privacy. “We did not migrate either in 2022 or this year, our children have remained in school and we are in our own homes,” she says.

Now, July has always been the start of the cotton picking season in the canal-irrigated districts and that was one activity the women of Thar never missed. Though the work was very hard, it nonetheless meant good money. But this year when the contractor came to recruit pickers from Old Subhani, Lakhma saw a relative and her husband preparing to go. “They would have been gone for two months and school was reopening in August. I told them to stay. There was plenty of work with the road building crews near the village. Here the men work during the day and come home to sleep with the family,” she says.

Convinced by Lakhma’s argument, the family turned down the contractor’s offer and stayed. The man and his older son are now employed on a road crew and as Lakhma said, both men return in the evening to sleep in their own home. And they together have PKR 1500 to show for their labours. She believes this being the only family that almost went and then didn’t in the end, it was the last time the cotton contractor called upon them. “He knows our ways have changed,” she adds.

On a more physical level, the village is turning green: women are planting trees in their courtyards. Besides the usual ber fruit (Genus Zizyphus) and date palm, women are experimenting with chikoo (sapodilla) and having heard from nearby villages that they do well, are also planting lemon trees.

A new level of awareness is now upon all the women who have undergone the CWSA training sessions. From Old Subhani and other villages, one hears a common refrain on how the gender awareness sessions have helped these communities. Customarily, men were served food first and the best of it too. Women satisfied themselves later with the leftovers. Now families dine together and the menu is shared out equally among girls and boys. The thought is banished that men having to go out to labour required better food. Now, they are mindful of the fact that tending livestock, fetching water from the well and keeping the home clean was also labour intensive.

Kasuba points out that chores outside in the fields are done collectively and when they are finished they collect firewood on the way back. She says that her son returns from school at 2:00 in the afternoon and after his meal, goes out to fetch water and firewood. Time was when firewood collection was considered manful enough, fetching water was strictly a woman’s job. Across the Thar Desert, the greatest mark printed in the sand by CWSA is the reason for communities to abjure the annual transmigration to join the wheat harvest and later cotton picking as a means of earning a livelihood. Their staying home means children who would otherwise have migrated with them in March and lost out two months of schooling before the summer vacations, now continue their education.

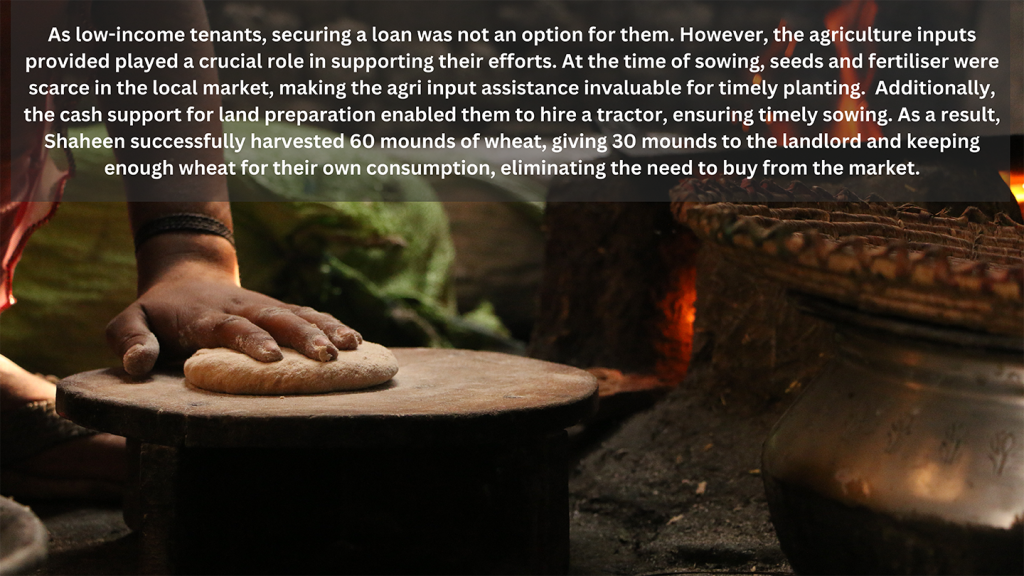

Sowing Prosperity

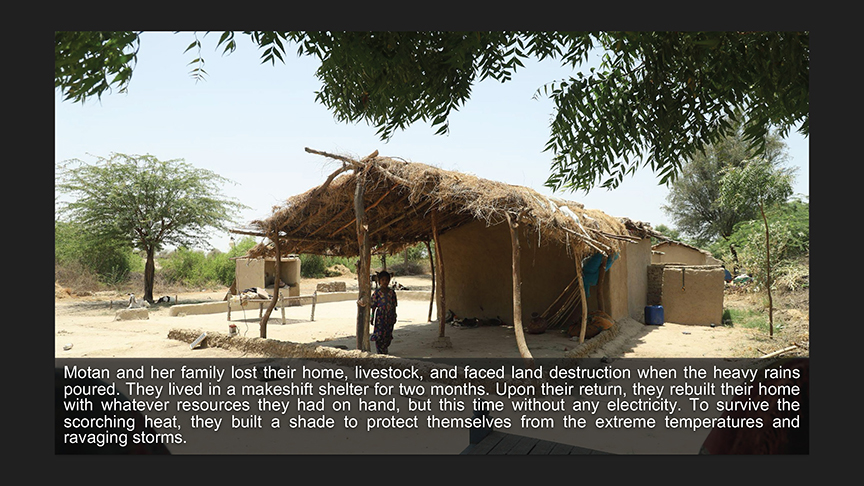

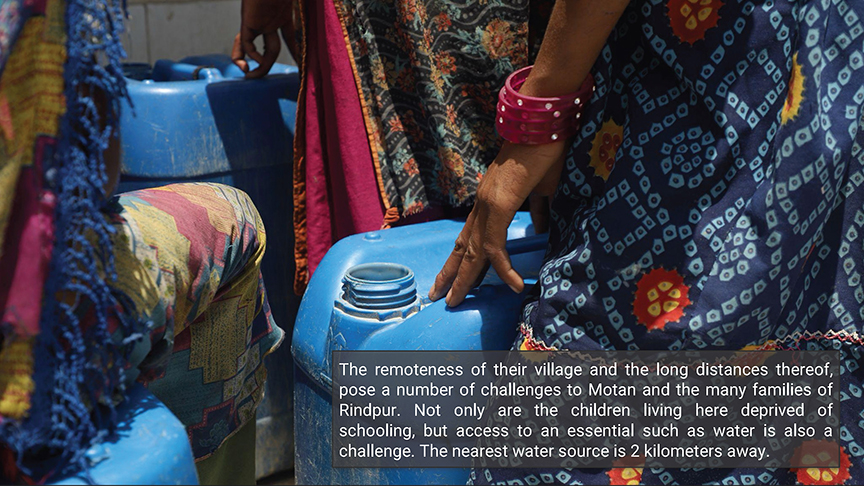

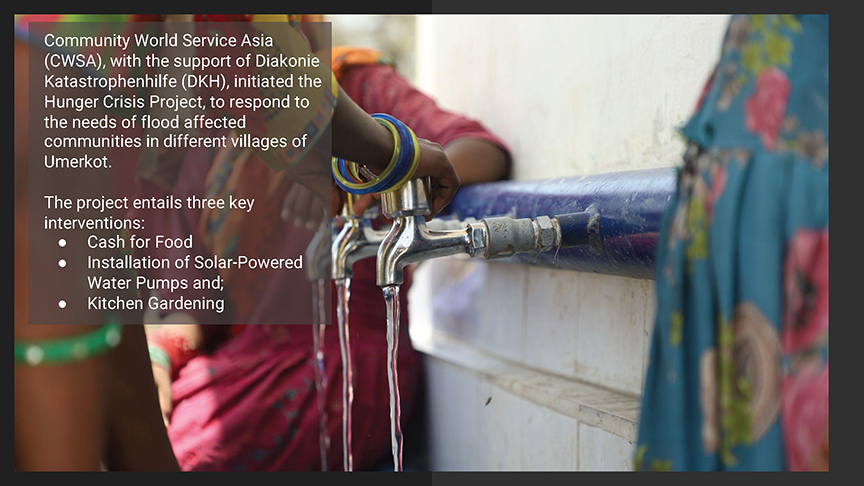

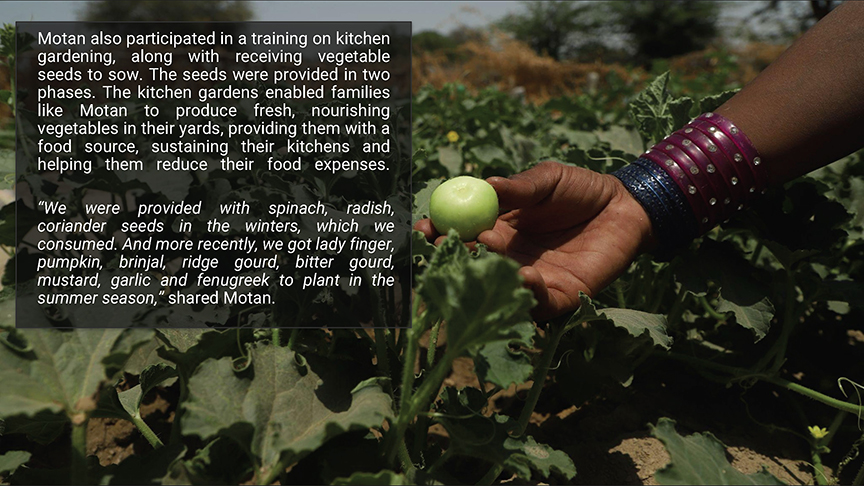

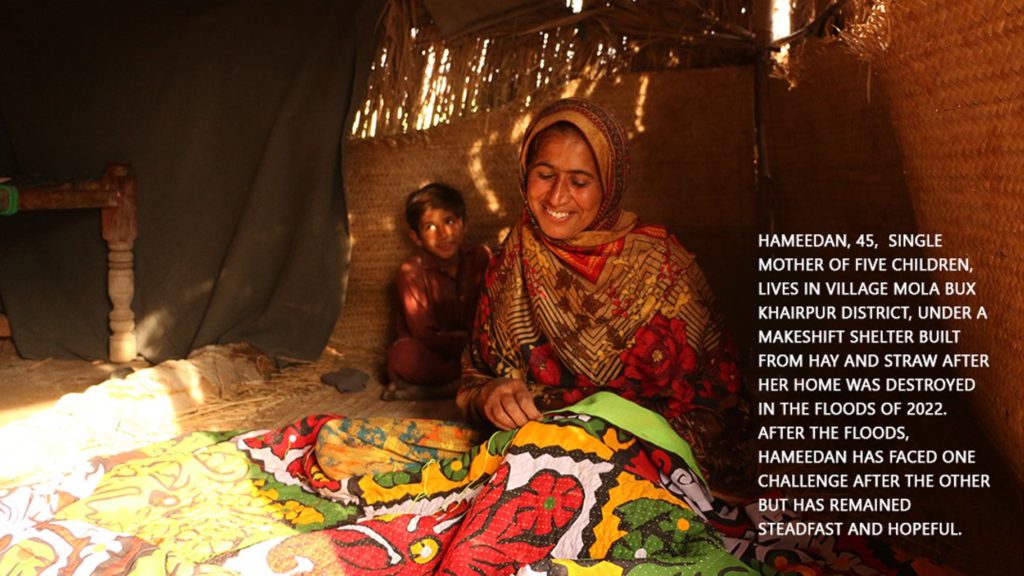

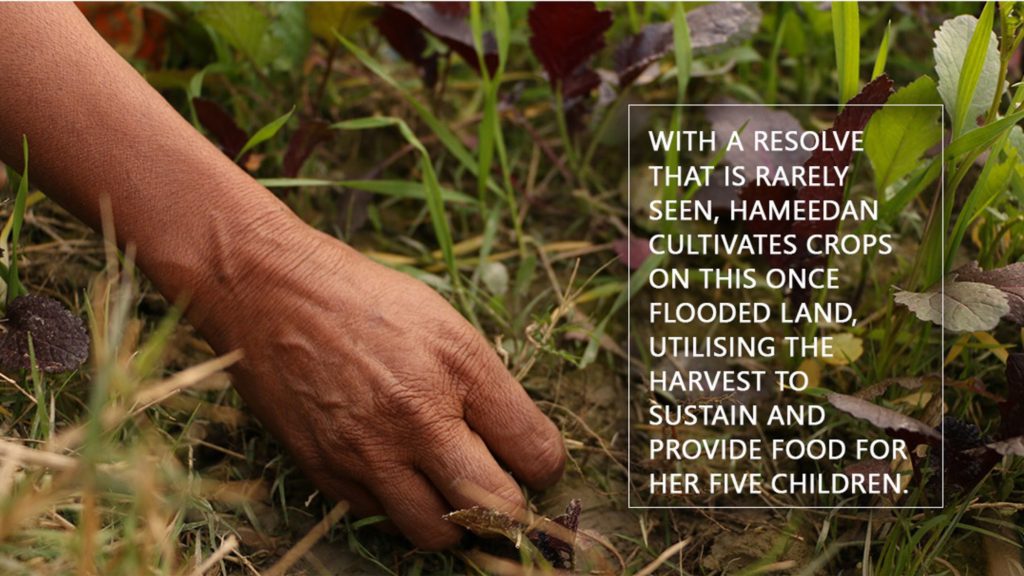

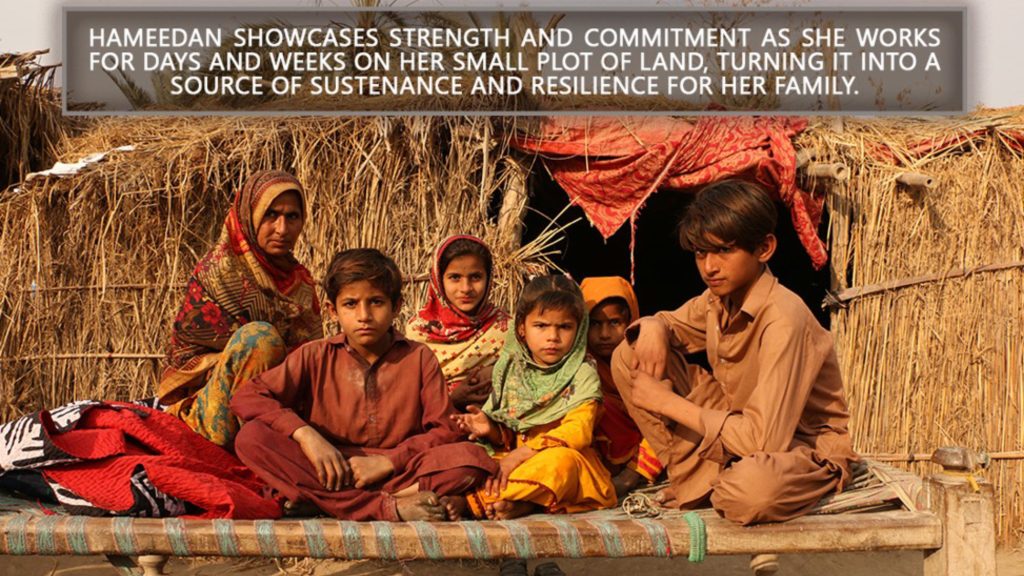

The Floods Took Everything, But Not Their Spirit

A survivor story

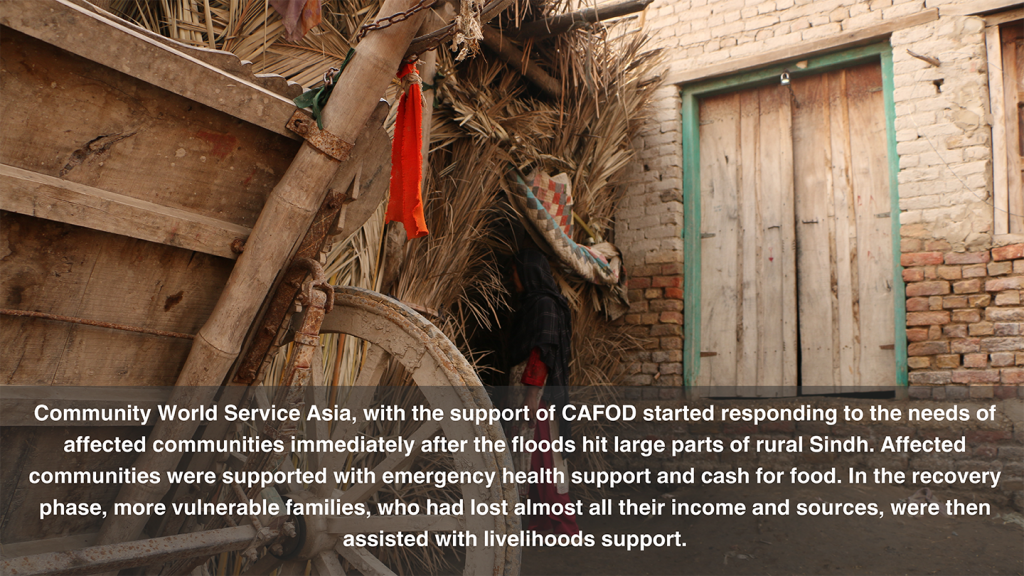

The floods in 2022 left millions of people in Pakistan displaced. Under the ACT Appeal, Community World Service Asia reached out to more than 7000 flood affected people (1099 households) by providing cash assistance to purchase food and essential household supplies. A total of PKR 60,000 (Approx. USD 203.3) was distributed in three separate tranches; in May, June, and July, with affected families receiving PKR 20,000 (Approx. USD 67.3) per month. This monetary support help meet their immediate food needs while also enabling them to save for other essentials, such as medical expenses, clothing, and more.

Hamzu Veerji, a 43-year-old mother of three children from Mir Deen Talpur village in Mirpurkhas district, was one among those supported through life-saving initiatives under this appeal. Hamzu and her husband, Veerji, have been married for fourteen years and have been pillars of unwavering support to each other. They worked together on agricultural fields of a local landlord as a means of livelihood before the flood struck their village. They cultivated and harvested red chillies on one acre of land and received a merger wage between PKR 150 to 200 (Approx. USD 0.51 to 0.68) per day.

Like many others from Mir Deen Talpur, Hamzu and her family was forced to abandon their home and belongings in haste, taking only basic food items (that would barely last them a couple of meals) and their two livestock—a bull and a goat, along with them. With not much money at hand nor a source of running income, the family had to sell their prized bull for a mere PKR 15,000 (Approx. USD 52). “Our bull was very precious to us and had been one of our key source of sustenance for years. We had no choice but to sell it. And that too at a very low price.” Hamzu and Veerji had purchased the bull in 2015 from a fellow villager for PKR 4000 (Approx. USD 14) as an investment to increase their livelihoods, as income from agricultural work was insufficient to provide for their children.

Without their cow and their daily wage, the family lived in a temporary shelter without proper protection on an elevated open ground for two months while waiting for the floodwater in their village to recede. Their village had accumulated up to five feet of water. When Hamzu and family returned to their village, it took them another two months to rebuild their mud-house; that meant more time under the open sky without a structured shelter or a roof to keep them safe. The family of five all lived and slept on just one charpai (a traditional woven bed used across South Asia). The charpai was among the few items they owned that had not washed away in the floods.

Hamzu and Veerji could not bear to see their children suffer these post-flood hardships anymore. But they felt helpless. Building their house again required a lot of time, strength and resources. All they were short on. “Initially, it began with the rain, followed by the challenge of enduring without food and shelter. Later, the heart-wrenching sight of our house reduced to a mere fragment clinging to life greeted us upon our return. Our children were profoundly affected, having already endured a great deal. My husband, Veerji, and I had to act swiftly to reconstruct our home, but the process of mixing water and mud was time-consuming, and allowing the structure to dry also required patience. Nonetheless, we made every effort to expedite the process,” shared Hamzu.

Access to clean water has always been a scarcity in Mirpurkhas. And the floods further exacerbated this issue. This meant increasing health problems among affected communities in villages like Mir Deen. The nearest well to fetch water from is at a six kilometres walk from Hamzu’s village and unfortunately this water is not even clean. This was a major challenge and concern for Hamzu and Veerji who really just wanted to ensure the good health and safety of their children. Luckily, with financial support from Community World Service Asia (CWSA) they were able to purchase clean drinking water and some groceries to stock up.

From the first instalment of PKR20,000 received, they spent ninety percent of it (Approx. USD 62) on groceries and drinking water and saved the remainder for future needs. “We used the money to buy sugar, tea leaves, rice, vegetables, and a few gallons of water, as the water we collected from the field was undrinkable. We could only use that to prepare the mud for our house.”

Hamzu prioritised purchasing abundant food for her family to protect her children from the risk of malnutrition, a serious concern in rural Sindh, especially among children in their formative years. Her youngest child, Meher, who is just 4 years old, had lost a lot of weight due to the lack of proper nutrition after the floods. Hamzu was now relieved that her children could consume nutritious meals and regain their ailing health.

The couple utilised the second instalment then for purchasing another goat (PKR 5000), to buy clean clothes (PKR 5000) for their children and the remaining on restocking food items. Hamzu explained their approach to managing the aid, stating, “With each instalment, we bought groceries and saved between PKR 2000 to 3000 for future needs, as we knew this assistance was not permanent. I discussed with Veerji the importance of saving money so that we can buy another bull, as it is the only way we can foresee now to improve our economic situation.”

Following the floods, Hamzu and Veerji found themselves without work and income but now they own two goats that provide milk, which they sell to fellow villagers. They have saved a total of PKR9000 (Approx. USD 30.5) up until now from the cash support provided to them. Hopefully in a few more months this hard-working couple will be able to buy a bull which will enable them to expand their income by selling its milk in the market.

Despite the hardships, Hamzu and Veerji value maintaining stability in their life for their children. With the support provided under the ACT appeal, they were able to rebuild their life step by step, with dignity and respect. Through careful budgeting and prioritising their family’s well-being, Hamzu and Veerji not only overcame their flood-imposed suffering but also created opportunities for a brighter future for their family.

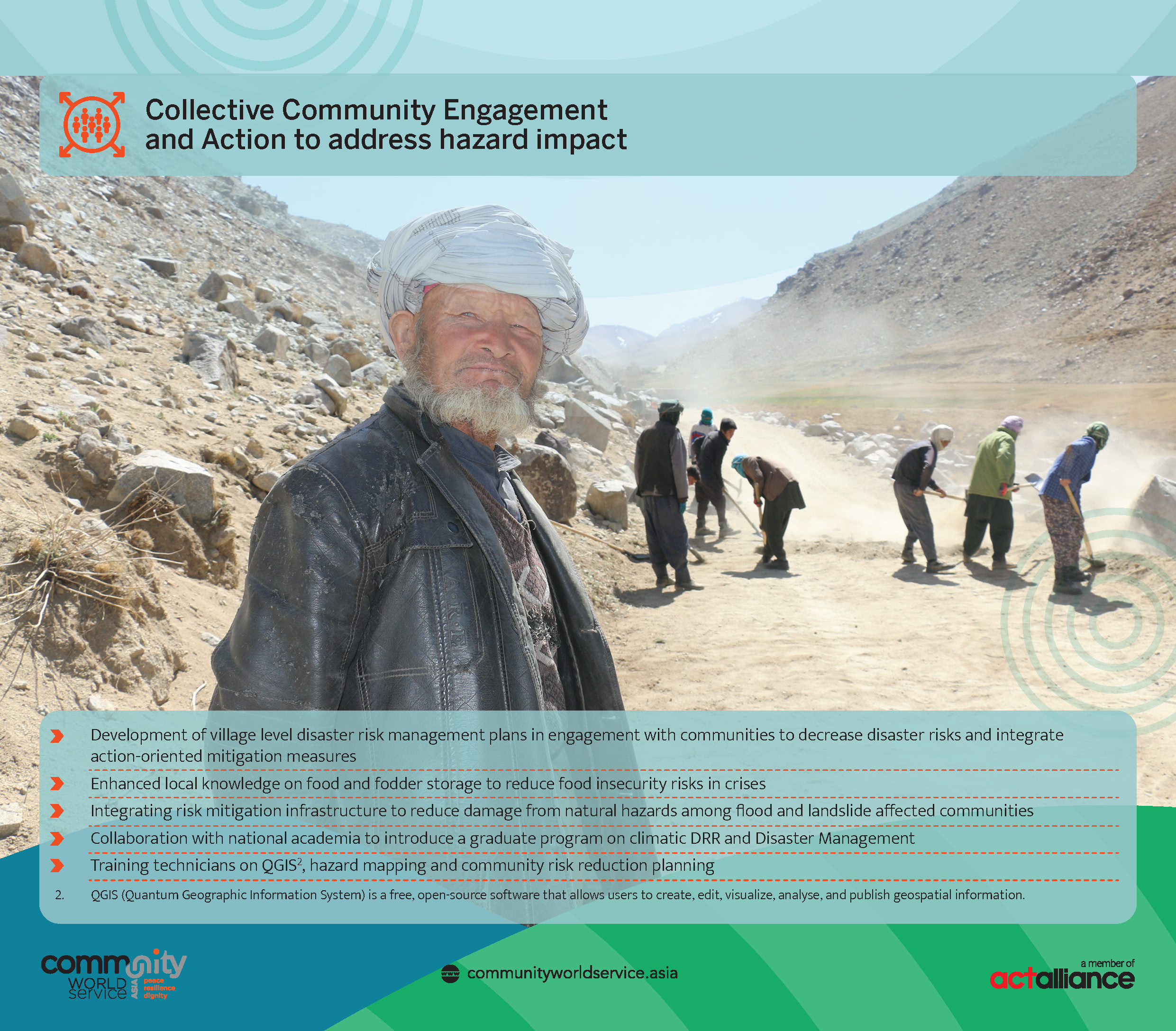

International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction

On this International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction, Community World Service Asia underscores its commitment to addressing the linkages between disasters and inequality. With continuous community engagement and the support of our partners, CWSA integrates Climate Action and Risk Reduction into its programming as well as into its organisational development. As we operate in a country (ies) that is at high risk of disasters and is among those with the highest share of the population living under the poverty line, we design projects, engage with communities and help develop long-term community structures that prevent and reduce losses in lives, livelihoods, economies and basic infrastructure caused by disasters.

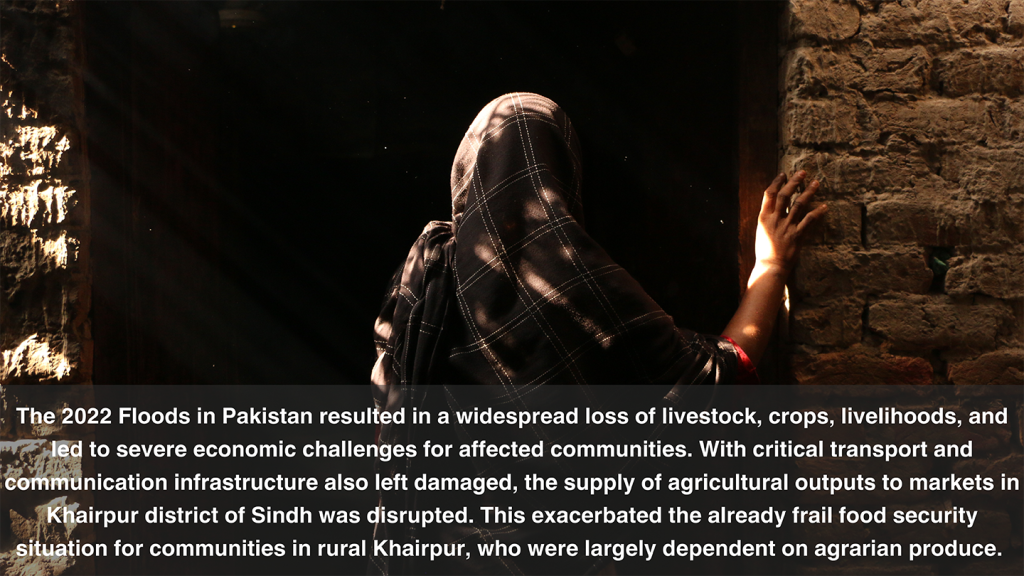

The 2022 Floods: A Wake-Up Call for Climate Action and Preparedness

#OneYearofRecovery

To put it simply: we in Pakistan are not prepared for natural disasters. One reason may be the fatalism that afflicts us and that God will be our saviour when calamity strikes. In fact, we leave much undone for God to step in to help when need be. No surprise then that during the few months of the year when our rivers run low, nomads, and sometimes even settled groups, build their homes in riverbeds. The Ravi River outside Lahore1 is a prime example of this occurring year after year.

It is also known that in the summer vacation district of Kalam (Swat), a hotel sitting right on the banks of the Swat River was swept away in the 2010 floods. The following year, the owner rebuilt his property on exactly the same spot. In 2022 it was washed away once more. There is a very slim chance that a lesson was learnt.

Downstream of Attock2, the River Indus creates a wide floodplain through Punjab and Sindh. In Punjab, the river flows virtually straight as an arrow in a south-westerly direction. But in Sindh it is an immense web of oxbows with very shallow banks. The fall of the land stretching up to almost 10 kilometres here is less than a metre. Moreover, unknowing to many, the soil of lower Sindh is virtually impermeable. Here water takes years to percolate into the aquifer.

It was seen that the water left behind by the deluge in 1987, was still sitting in the ditches by the roads five years later. In the districts of Badin and Mirpur Khas, lakes had formed where migratory birds like flamingos and pelicans were wintering in 1992. Likewise, the dry oxbows of the old bed of the Indus in upper Sindh turned into major water bodies that remained for several years.

The flood of 2010-11 was one thing. In 2022, it was simply biblical. Throughout Sindh, men related that once the deluge began in July, it continued for a full forty days with short gaps in between. Whereas mud and wattle huts stood no chance under the cascade, even brick and masonry homes started to collapse after a couple of weeks. These latter are of two types. The one with a proper cement concrete slab lintel for the roof; or the less expensive one with a girder and cross strips inlaid with tiles. In many cases the walls are just one brick thick.

As the skies sent down cascades of water, the Indus too rose from the deluge in its upper reach. Millions of acres of farmland went under as the oxbows overflowed turning the land into a very sea. Date groves with their fruit ready to be picked were flooded killing off the trees at worst and best damaging the fruit. Sindh, famous for its cotton output, lost virtually all of its cotton crop. The vast vegetable patches in the floodplain that had remained dry since 2011 were drowned.

When it is not in spate3, the Indus floodplain is very fertile farmland and all along its course through Punjab and Sindh the loamy soil is used extensively for wheat and vegetables that can be harvested before the summer thaw in the mountains reaches the plains. In 2022, farmers along the river were able only to reap their wheat and collect their vegetables before May. Anything that remained on the stalk was destroyed.

This year, there was no farmer in the Sindh plains along the river who so much as made good their agricultural expenses. And since the practice has long been to make this investment on credit, thousands of farmers went under huge debts.

Loss of agriculture was something that could have been overcome and indeed the milder monsoon of 2023 has ameliorated the agricultural scene to only a little extent because when sowing of wheat commenced in December, the soil was still waterlogged. As a result, the yield was very poor in March. If submerged farmland has to be reclaimed it needs a giant effort by the government to pump out the water. Individual farmers who can afford it have been seen doing such dewatering, but the magnitude of the job is way beyond the capacity of individuals and the civil society.

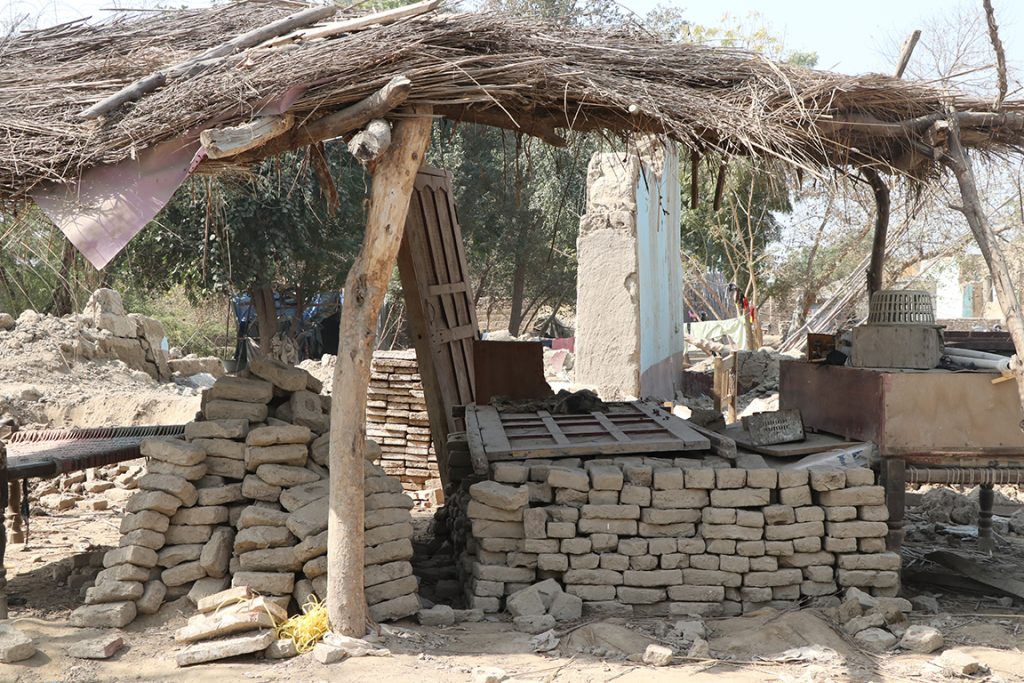

However, it was the loss of housing that broke the backs of the farming communities across Sindh. With their incomes lost, they were unable to rebuild and a year after the deluge, innumerable families are still living under makeshift shelters.

The cash assistance of PKR 48,000 (Approx. USD 156) in four equal instalments to affected families under one of CWSA’s flood response projects, was some help but as Shams Din a sharecropper of village Ismail Sanjrani (Khairpur) said it was like ‘salt in the flour’, in reference to the pinch of salt added to flour before kneading. His two-room house built many years ago was a heap of bricks and clay after the deluge and the cost of full reconstruction with current inflation was PKR. 300,000. With the little help he had received, he hoped to raise the walls to lintel level. Across it, he said, he would stretch the tarpaulin that currently made his home.

Even holders of ten acres of irrigated land in the district were hardly any better off. With their agriculture completely lost, and their more spacious houses either completely razed or with just the walls rebuilding would cost way more than what poor Shams Din does not have. The hope in early 2023 was that there would be no visitation and that their agriculture would yield sufficient profits to start rebuilding.

The greater losers, however, are owners of fruit orchards. Lemon, mango and date that grow abundantly in Khairpur district yielded nothing leaving fruit farmers under huge debts. The flooding left large number of these trees not just fruitless, but dead. Some of these orchards, particularly lemon, were planted only three years before the flood and the owner had barely repaid the loan for the purchase of the trees. Just when they thought they were heading for a profitable harvest, all was lost.

In the south in Mirpur Khas district, the story is not very different. Thousands of acres of farmland now look like lakes. Here the damage was done as much by the nonstop rain as it was done by the overflowing Left Bank Outfall Drain (LBOD). For years this drain meant to carry effluent to the sea had been no more than a trickle. Consequently, influential landowners encroached upon its course, blocking it to create farms where historically only barren land had spread.

When the Indus overflowed and with it LBOD, towns and villages around Jhuddo went under. The damage around Jhuddo was mainly because of the unofficial damming of LBOD in its lower reach: it may have blocked tainted water flowing into the farms of the rich and powerful, but it created havoc for ordinary people.

While housing and agriculture was lost, the additional damage was done by the overflowing of effluent from LBOD. The common complaint here, as in Khairpur and other areas, was that flooding had tainted their hand pumps. Thousands of people were therefore drinking poisoned water causing skin and gastro-intestinal diseases. Primary health care units were unable to cope with the flood of humanity pouring in without outside help. Health camps established by CWSA provided some succour. The disaster was simply too great and widespread for its effect to be mitigated by these heroic but small initiatives.

While the civil society has been hard at work, their effort is still too little compared to the impact the floods of 2022 has had on the people of Sindh. A greater effort is needed to bring back people’s lives to normal.

- Capital city of Punjab province. The second largest city in Pakistan and 26th largest in the world, with a population of over 13 million.

- It is the headquarters of the Attock District and is 36th largest city in the Punjab and 61st largest city in the country, by population.

- A sudden flood in a river