Countering the Infodemic

Photo credit: Suwaree Tangbovornpichet/Getty Images

Prepared by CWSA, BBC MA and First Draft

In the COVID-19 pandemic, each one of us is responsible for slowing the spread of the virus. Every action counts. Similarly, one must be accountable in the fight against propaganda, and the spread of misinformation, rumours and hear-say. The rise of digital and social media has enabled the spread of misinformation at a speed and scale not seen before. The World Health Organization (WHO) has described this phenomenon as an infodemic. We, the civil society and responsible media, acknowledge that the infodemic has spread faster than the pandemic itself and action must be taken at a personal level to mitigate this.

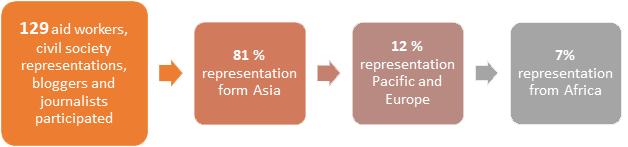

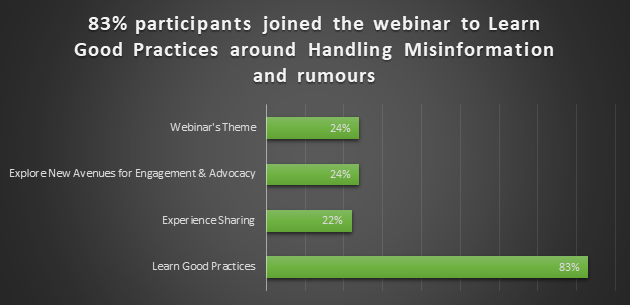

Community World Service Asia, BBC Media Action and First Draft jointly hosted a webinar on Understanding and Handling Misinformation in the COVID-19 context. Genevieve Hutchinson, Senior Health Advisor, BBC Media Action moderated the session and was joined by speakers Victoria Kwan, Ethics and Standards Editor, First Draft and Radharani Mitra, Global Creative Advisor, BBC Media Action.

The 90-minute webinar discussed an overview of the current infodemic, the reasons behind and challenges faced because of the spread of mis and dis- information during the COVID-19 pandemic and best practices and strategies for best addressing and handling this sort of a communication crisis.

“The infodemic related to COVID-19 started incredibly quickly. By the end of January, there were already WhatsApp messages, claiming to be from a Ministry of Health or from different governmental offices going around multiple countries. These messages claimed to share preventive measures of coronavirus, except all the information in them was false,” said Genevieve. “There was a challenge to handle a mass of information which was both false and fact based.”

Research on social media propaganda shows that bystander inaction can encourage the proliferation of fake news. Anyone with access to the internet can contribute to the war on misinformation.

It is essential to work on this together as misinformation affects everyone.

“It is not just a communication issue, it is not just a media issue and it affects us personally and professionally,” Genevieve said.

What do we mean by misinformation?

Misinformation can refer to a range of false information, including:

|

|

Misinformation about health or any other issue is not new. Long before the internet era, people have faced the challenge of misinformation. The issue now is the speed in which it travels; the nature of social media and the internet means that there is a lot of misinformation that can be created and shared within a matter of minutes to millions of people. This can be done without verification. The more the information is shared, the more credibility it gains.

“The challenge is that misinformation can have negative impacts. It can harm human reputation, it can cause widespread uncertainty, panic and fear and it can make people take decisions that are harmful to themselves or others. And we have witness this in the case of the current pandemic – COVID-19,” emphasized Genevieve.

When the pandemic started, First Draft staffers around the globe began tracking the kinds of coronavirus content that was available online to identify patterns and trends that they could then share with newsrooms and other communications professionals. Some of the challenges identified in this process included:

|

|

“One thing that makes the current infodemic different is the sheer quantity of information that is flooding the online ecosystem. It is coming at a time when people are feeling particularly scared and vulnerable and when there are so many unknowns about the virus’ origins and treatments. Low-quality information can add to the noise and drown out high-quality information,” shared Victoria.

Humans do not have a rational relationship with information but an emotional connection felt with the information that is received and shared.

“This is the part that makes the infodemic very challenging. We need to understand why people are sharing misinformation and create content and strategies to address that. We need to further think on how we can help people change attitudes around sharing. Media literacy efforts to teach people how to stop and think before sharing are incredibly important,” added Victoria.

The human brain is able to process and recall visuals much faster than a text, which makes the memes and pictures very effective. Placing emphasis on the impact of visual misinformation, Victoria said,

“The visual content is tempting to share sometimes as people think it is funny or it’s amusing. It can feel harmless to share it. But when it is forwarded a number of times to the wider audience, it can become a problem. It is also more difficult to track and monitor visual misinformation compared to textual misinformation. To meet these challenges, we need to develop better ways of tracking visual misinformation. We need to learn how to counteract misinformation with visual content of our own and understand the attitude of people sharing these visual contents.”

Journalists play a crucial role in getting accurate information out to the public, but face the challenge of cutting through the noise. To help meet these challenges, First Draft has created a free Coronavirus Course, which may also be of use to NGOs and other community groups. Provided in six different languages, the course will walk you through how and why false information spreads, provides techniques for monitoring and verifying information online and shares best practices on slowing down the spread of misinformation.

Additionally, First Draft believes that collaborations between newsrooms is crucial. Collaborations can help newsrooms avoid duplication of efforts such as in the case of verification of specific information. In addition, it also allows newsrooms to examine the kinds of misinformation and rumors that have spread in other regions, and anticipate what their own communities might be seeing next.

The media can help curb widespread misinformation. BBC Media Action has been providing people with accurate and relevant information including fact checking. They have created a space for discussion, dialogue and reflection on issues that can drive the spread of misinformation. They aim at influencing attitudes and norms behind sharing mis- and disinformation online and improving critical digital and media literacy skills among audiences.

BBC Media Action has adopted social and behavior change communications (SBCC) approaches to influence audiences’ behavior in relation to issue that can be subject to misinformation.

“We take a more holistic approach to combat misinformation which includes capacity strengthening of media practitioners and organizations and to broaden the agenda around media development to support and strengthen the quality and independence of media,” explained Radharani.

There has been a range of COVID-19 related content created by BBC Media Action.

“In all of the countries where we work, we have established audiences from existing programs across a range of media platforms from TV to radio and to various social media channels. Consequently, we were able to revert the audiences in a fast pace who required information on COVID-19 and we capitalized on the existing relationship engagement and trust we had with these audiences. Much of this has been done online as it’s the fastest way to get content out and reach mass audiences.”

Radharani highlighted that it is not merely enough for health information to be credible, it also needs to be grounded in the realities of the target audience and it must be contextualised to be accurate and effective. Messages on COVID-19 awareness need to be localised using local talent and local languages to make an impact that is required for a pandemic of this nature and magnitude.

Radharani highlighted that it is not merely enough for health information to be credible, it also needs to be grounded in the realities of the target audience and it must be contextualised to be accurate and effective. Messages on COVID-19 awareness need to be localised using local talent and local languages to make an impact that is required for a pandemic of this nature and magnitude.

“We initially aimed at providing factual and accurate information, to build understanding about prevention and what to do in the case of suspected symptoms of coronavirus with the focus on quality information rather than quantity. It has been a two-fold strategy, to work as quickly as possible and creating content that is generic enough so that it can be shared across countries and can be easily adapted for any country or any language. We have also worked on developing country specific content suited to a particular context,” Radharani said.

In addition, BBC Media Action has rolled out online and remote training and mentoring for local media on how to respond to the pandemic, available in multiple languages.

Mitigating Misinformation in the COVID-19 Context

Participants asked how they could fact check and verify information.

“There are different tactics that can be used. We encourage the audience to do lateral reading, which means looking at other trusted sites and resources and examining what they say about the claim you are seeking to verify. In the case of an image, conduct a reverse image search on Google or Yandex and verify whether it actually depicts what it claims to depict,” advised Victoria.

Radharani added that one has to be extra vigilant in groups where mass information sharing takes place.

“If one feels any doubt about a piece of information, it is important to call it out immediately. We have to be cautious and encourage skeptical behavior to combat misinformation.”

Her top tips are:

- Understand (and listen to) your audience(s) and keep an eye on rumours and misinformation that are circulating

- Tailor content to context where possible

- Provide clear, simple, precise and actionable information

- Be credible – use trusted voices or communication platforms

- Remember the battle for engagement – and so the need for engaging and shareable formats/ approaches

- Quality, not necessarily quantity

- Follow the 10 seconds rule: Stop and think. If you have doubts, do a quick research before sharing ahead

- Influence attitudes and norms around sharing information – it’s not all about fact-checking

There were questions raised on how to address misinformation with organizations who have limited access to media in the context of the current pandemic. Radharani addressed the question saying,

“We have developed a series of audio messages on hand and respiratory hygiene, social distancing and symptoms and treatments. This has been specifically developed for rural audiences. For this reason, we have tied up with the aggregator of community radio stations. Our audio spots will be heard across community radio stations that are reaching people residing in remote areas with limited access to smartphones. We have to tailor dissemination and broadcast strategies and they have to be bespoke to the situations we have on hand.”

Participants also asked about how people could strike a balance between sharing healthy awareness-raising information and that which would cause anxiety. The content we see every day can be distressing and tiring, and it can feel like we do not get a break from it even outside of work. To address this, its best balance to out the negative content with some positive content, like number of people who have recovered and how families are spending more time with each other and news that exhibits “good vibes”. It is also recommended to rephrase the language so that it’s not panic-inducing or too alarming.

Questions were asked on how to manage and counter misinformation through social media.

“We need to keep trying to change the culture around sharing misinformation. In addition, we need to encourage people to practice emotional skepticism and thinking before passing on information to others. We also need to do a better job of explaining the tactics and techniques behind misinformation. Audiences should be made aware of the different types of misinformation and why is it so easy to believe them,” suggested Victoria.

Participants inquired around methods to track rumors and if they were available online, in order to combat that spread of misinformation. Radharani addressed the question saying,

“The responsibility to track how misinformation is spreading is not up to an individual. This is where media development comes into focus. It is to build the capacity of journalists and media professionals so that they can fact-check. As far as individual behavior is concerned, we’ve tried to build their confidence and competence in feeling more responsible while sharing, making people more conscious of sharing, and work on their media literacy.”

Useful Resources

- How to protect yourself in the infodemic? By WHO

- Covering coronavirus: an online course for journalists

- 1st WHO Infodemiology Conference

- Don’t get duped. Just learn to verify – Training course

- First Draft’s Guide to Verifying online information