The Shift of Power – Localisation in COVID-19 Response

Photo Credit : DFID – UK

This is a real opportunity to discuss localisation. For many years, local actors have been the first respondents and it is very important in this current pandemic that we now focus on what the key role of local actors is? What have they contributed? How do we go forward from here?

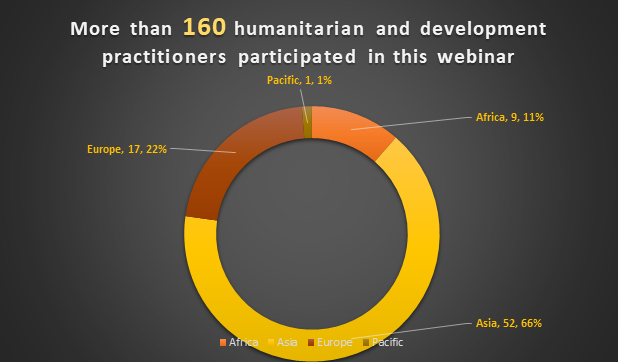

Smruti Patel, Founder and Co-Director of The Global Mentoring Initiatives in Switzerland raised these questions while moderating the webinar on ‘Localisation during COVID-19’ on June 2. Jointly hosted and organised by Community World Service Asia and the Alliance for Empowering Partnerships (A4EP), the 90-minute webinar provided participants a platform to exchange and discuss experiences on how localisation is progressing in the different regions, the challenges it has encountered so far and the way forward to effectively implement it.

Dr. Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, Director Lebanon Support, Beirut and Naomi Tulay-Solanke, Founder Executive Director, Community Health Initiative (CHI), Liberia, joined Smruti Patel as speakers in the webinar.

Participants from across the world shared best practices on how they have taken into account the current crisis, including collaborating and advocating for localisation on a national, regional and international level. Forty percent of the participants represented local and national organizations.

A Unique Challenging Context

The COVID-19 pandemic has become the greatest public health issue of our times and is defining the global health crisis today. In comparison to the loss of life and the destruction to millions of families, economic harm from the crisis is now substantial and far-reaching.

The COVID-19 Crisis Response and the Global Humanitarian Response Plan (GHRP) offer incentives to drive momentum on the Grand Bargain commitments and address structural inequities. State and regional civil society organisations have a vital position to play and have been at the center of the response to COVID-19.

We have seen unparalleled support from local organisations, including the response to delivering awareness to their neighbourhoods, supplying food and hygiene kits along with addressing certain core needs. They were at the forefront of the first response. Some have brought these initiatives to their own sponsorship through collecting funds by community members, residents and joint activities, said Smruti.

Regarding constraints on movement and mobility, local and national humanitarian actors are on the forefront of the COVID-19 response, working in places where the risks are highest. Through this response, there has been a significant shift of operational burden to local and national players, in comparison to the normal ‘upsurge’ of international workers in reaction to the crisis. These discussions aimed to capture the views of local and national NGOs and the recommendations from the discussions will contribute to the GHRP revision progress, which takes place after every six weeks.

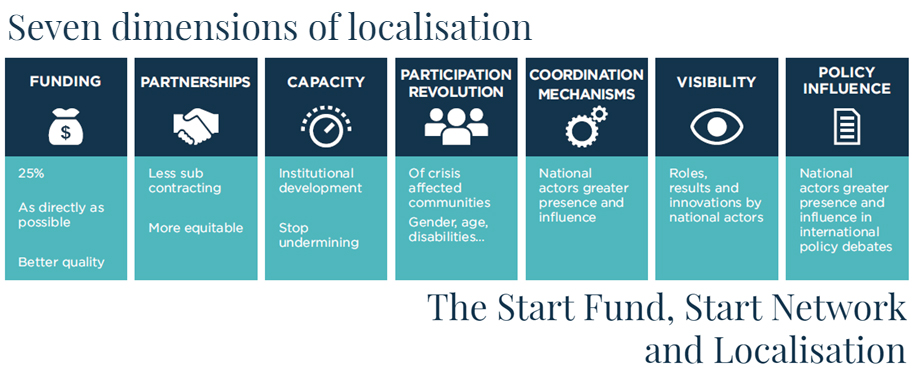

In 2017, a research of Global Mentoring Initiatives with the START Network developed the seven dimensions of Localisation Framework by engaging local, national and international organisations in discussions highlighting the significant aspects to make localisation successful.

The framework takes a deeper and more critical view of localisation, assessing the quality (not just the quantity) of funding, partnerships and participation, capacity development, and the influence of local and national organisations. It seeks to promote granularity in the sector’s understanding of localisation, in order to foster a holistic approach to addressing it. Steps to make these dimensions a reality:

- Maintain quality of partnerships and ensure equitability and respect

- Promote accountability to affected populations and local actors and keeping them at the center is key

- The quality of funding should be flexible and developed in collaboration with local actors

- Capacity building activities should be aimed at sustaining the organisations and they should not be undermined by the way the international response takes place

- It is essential that National & Local actors take leadership in coordination mechanisms to influence decision-making at a broader level

- Active visibility of response of local actors can build strong trusts among communities

- Local and national actors need to be present in international policy debates and discussions

The Implementation Gap

reiterated Naomi Tulay-Solanke. In 2014, when the Ebola hit, local actors accelerated at a different level because of active advocacy and exerted the INGOs to practice equal partnership and invest more in localisation. Although Covid-19 imposed a focus on local interventions and a scale back to national borders, Localisation is yet to happen by design. Naomi says,There has been a little change. Now we can have a pen discussion on localisation. We now have documents to hold INGOs on account. We have all set the pace,

INGOs have recognised the importance of partnering with local actors now. That is a gain, compared to 2014, where we were considered as local contractors. However, there is room for improvement. This can only happen if we persistently engage in a constructive manner, taking everybody on board, holding them accountable on signed documents especially at community and national levels.

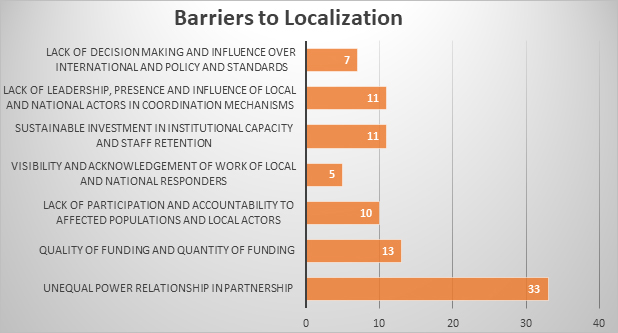

While a majority (33%) of the webinar participants cited “unequal power relationship in partnerships” as the main blockage for localization, speakers provided additional insights and nuance to the many aspects relevant to localisation from the perspective of actors from the Global South.

Although Covid-19 has imposed a focus on local interventions and a scale back to national borders, it was agreed in the discussions that Localisation is yet to happen by design. As Naomi Tulay-Solanke reiterated,

we need to be at the table when the project is being designed, and to be engaged in a constructive manner.

Global organisations including INGOs and donor agencies are on path with the local actors. They understand the local actors, their ideology. However, when it comes down to the national level, it is a different ball game.

There are more local actors like never before in the current COVID-19 response. As COVID-19 is a global crisis, it took a while for international organizations to come to Liberia. We have witnessed a different kind of partnership with the donor agencies. The employees of donor agencies are on the ground implementing the project activities and the local organisations are taken in loop to monitor, said Naomi.

The turning point, however in other disaster and conflict affected countries, such as Lebanon, is not the current global pandemic. It is an additional layer of a multidimensional crisis the Lebanese people have been witnessing since the beginning of 2020.

Information is a very powerful tool. As a driver of any issue, we want to advocate, we need to know what we are talking about in advance. The seven dimensions are insightful, as we need to break the challenges down into measurable features and take ownership of the narrative, expresses Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi,

We need to frame the narrative of localisation as we are rooted in our communities. We know what they need and where the interventions need to be executed.

Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi highlighted the necessity to take control of the narrative around localisation whether in its definition, in partnerships, in solidarity, and develop in practice alternative ways to implement localisation, and break out from dependency on the aid industry.

What is the meaning of partnership? Marie-Noëlle asked participants.

In our organisation we do not use the term partner. We firmly address our funders as donors, unless there is a shift in the power dynamics. We need to start using terms for their actual meaning.

The principle of mutual accountability is key. The concept of balanced and equitable partnerships needs to be promoted.

We are equally accountable to tax payers as we are to the project participants. Any discussions on trust and accountability that does not take into consideration this whole spectrum, misses the point. We must refuse our participation in these partial and biased discussions, said Marie-Noëlle.

Participant Reflections

Participants shared best practices and reflections from their experiences on the ground and at different levels of a humanitarian and development work.