Archives

A School Reborn

Though Kumbhar Bhada lies only 45 kilometres east of Umerkot town, its setting among vast sand dunes gives it the feel of a remote desert settlement. Home to around a hundred families, all of whom are Muslim, the village has long struggled with limited educational facilities. Two government schools exist, one co-educational and another for boys, but opportunities for girls have remained scarce. In the early years of this century, the government allocated a single room to function as a girls’ school. For a community where families often have ten or more children, this provision was far from sufficient, leaving many girls without access to meaningful education.

No official teacher was appointed, however. In this vacuum, an NGO sent a woman teacher to work in the village. This private project lasted some five years and with its end the school closed down in 2007. Though some rare girl students joined the boys school, most simply dropped out and became their family’s help in household chores or in the fields. In a nutshell, since about 2007 there was no girls’ school in the village. For parents, themselves generally uneducated, this was no significant setback. Girls at home meant they could be gainfully employed with the parents to help at home and in the fields. However, there were also those rare parents who wanted their daughters to be educated.

In January 2024, community elders appealed to Community World Service Asia (CWSA) to revive the abandoned girls’ school and bring it back to life with a dedicated teacher. Responding to this call, CWSA appointed a qualified woman teacher and equipped the school with resources to make learning both meaningful and enjoyable. Children were introduced to sports equipment such as hoops and balls, and delighted in the novelty of a steel frame fitted with two swings. Classrooms were enriched with colourful teaching aids, foam blocks marked with alphabets and numbers, along with picture books, transforming lessons into engaging experiences.

Another highlight, under a sister project also implemented by CWSA, was the introduction of a school feeding programme, ensuring that every child received a nutritious lunch. The menu varied daily, with vegetables and lentils forming the staple, and chicken biryani served once a week, a meal that not only nourished but also brought joy to the students. This initiative helped safeguard children from malnutrition and encouraged regular school attendance.

As the single classroom could not accommodate cooking and serving, the community rallied together to expand the facilities. A hut was built beside the classroom to serve as a dining area, while a small shed became the cookhouse. The village community centre was also handed over to the school, repurposed as a pantry. These collective efforts created a welcoming environment where children could learn, play, and thrive.

Rather tentatively the attendance register listed some 35 students in the first week. Numbers slowly ticked upward and soon there were 80 until the rolls now stand at 120. As the students take their classes in the single room, two local women in the hut adjacent to it prepare lunch. During the break, the students take turns, 20 at a time, to be fed.

Gulshan, third among five sisters and seven brothers, is in Grade 2 and says she is eight years old. She started classes some years ago in the coeducation school, but soon dropped out. She has no idea if her parents thought it improper to her, a grown girl even at the age of eight, to be studying with boys, but she says she was put to work helping her mother with household chores. During the farming season, she went with her parents to their small holding where she minded her younger brother while the parents worked.

Though one of her older brothers takes local transport to Kaplor, six kilometres away, to attend school in Grade 5, none of her other sisters are in school. Some of her younger siblings do attend the local mosque for religious lessons, however. Quite clearly her family is not one that lays any great merit on girls’ education.

Gulshan has been in school since it restarted in January 2024 and in almost two years has worked her way to Grade 2. In between, her attendance became irregular and she relates that her parents would take her to work in the fields. Outside of farming season, when her father goes to work in a confectionery shop in Karachi, her mother insists she stays home to help with housework. She says she wanted to be in school and it was only after much pleading with the elders that she was able to resume classes. She affirms that she will continue to attend school even if the lunch programme comes to an end when the CWSA project ends in 2026. She has to fulfil her dream of being a doctor one day.

Eleven-year-old Ayaza, the third among three sisters and six brothers, carries a story marked by resilience. Living with a polio-affected leg that causes her to walk with a limp, she refuses to let this challenge define her. In fact, she considers herself fortunate compared to one of her brothers, who suffers from polio in both legs and can only crawl. When her parents are busy tending their small plot of land , where Ayaza also lends a hand, her father supplements the family’s income by working as a labourer on construction sites. For the family, however, education has never been a priority. Only one of her brothers attends the local boys’ school, leaving Ayaza and most of her siblings without access to formal learning.

When asked about her future, eleven-year-old Ayaza speaks with quiet conviction. After completing Grade 7, she dreams of becoming a teacher. Her heart is firmly set on this path, and she insists she will do whatever it takes to achieve it. For Ayaza, the daily school lunch is not the only motivation to attend classes; she carries with her higher ambitions and the hope of shaping young minds one day.

For Grade 2 students, both girls read surprisingly well from their primers. Even random pages are read fluently. This surely is a reflection on the efficiency of the teacher and her teaching methods.

In the two years since CWSA rehabilitated the school, a Children’s Day and a Cultural Day festivals have been held. Both events were fun-filled days of games and eats attended by students of the other two schools as well. According to the parents, despite the schools functioning since the mid-1990s, these events were the first such to have ever taken place in the village. It seems this might be the reason parental interest in their children’s education has risen and the students are not being withdrawn to help at home.

As the CWSA project draws to an end in late 2026, the school will be handed over to the government and a lady teacher appointed here. Going by the yearning for education seen among the students, it is clear that the village committee will raise a clamour in the event of government apathy. Surely children like Gulshan and Ayaza and all the others who dream of being useful adults need to be given the chance to prove themselves.

Upwardly mobile Ameenat Rind

In 2016, Nangar of Mallay ji Bhit died of tuberculosis of the lungs. In his final weeks, he was also haemorrhaging violently from the nose and mouth and had to be hospitalised in Karachi. In that trying time, Ameenat tended to her home and five daughters while her only son looked after the ailing father in the hospital. Ameenat says her husband’s hospitalisation cost the family about PKR 400,000 (approx. USD 1428).

She sold her two buffalos, one cow, three goats, a donkey and the cart to pay for the treatment. But when she was left with nothing more to sell, she borrowed from family and friends. Sadly, Nangar’s illness was so far gone that there was no coming back and when he passed away, Ameenat was under a debt of PKR 250,000 (approx. USD 893) and with no assets. She was lucky that her relatives wrote off their loans to her. There still remained a substantial sum owed to others. She and her eldest son eventually repaid after much hard work over three years during which she worked as a sharecropper, while her son tended other people’s livestock.

Ameenat’s most handy skill is mud plastering of houses for which she is called by householders in the village. As well as that, during season she goes chilli pepper or cotton picking which fetches PKR 500 (approx. USD 1.79) for every 40 kilograms picked.

Between 2021 and 2024, things were comparatively better for her and she wedded off her son and two of the older daughters. To complete the count, she says, she still has to wed three more girls. Now with her son working as a helper on a waste management truck for PKR 15,000 (approx. USD 54) a month, she was always worried it would take a long time to arrange the necessary dowry for the girls.

“My son gives me Rs 5000 to 7000 [approx. USD 18 to 25] a month from his salary. But that is only enough for household expenses, not to put away for dowry,” says Ameenat.

Her fortune changed when she became one of the participants under a food security and livelihoods initiative implemented by Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and financially supported by Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe (DKH). In October and November 2024, she received the first two installments of multi-purpose cash assistance under the project. That year, her portion as sharecropper was reasonable and the cash was used partially for food while the bulk was spent on dowry items. It was the goat that came with the package that was the biggest boon because it soon delivered a very healthy kid.

Ameenat says she would normally have worried about the health of her goat in the dry season starting in March, but in 2025, she had hydroponic fodder to augment the dry fodder she had saved from the past harvest. The kid gambolling around her yard looks very healthy and she says though it is now weaned, it had plenty of milk when it needed because of the green fodder she was trained to grow. The bonus was the supplemental feed for the goat which also increased its milk production and she was able to have her own supply for morning and evening tea.

The kitchen garden was another great bonus. Since the death of Nangar, the family rarely had vegetables to dine on but that was not the case now. This was only when her son came home for a day or two and brought a supply from town. In November 2025, she was preparing her little patch for the third round of gardening.

“We used to have homemade chilli and garlic chutney with chapatti [flatbread] because we could rarely afford vegetables. But now there is so much and in such variety that when vegetables are in season we always dine well and also give away to others,” says Ameenat. She is proud that she now entertains visitors with good milk tea and excellent vegetable stews.

“Since this intervention, our life has changed for the better. I can now look forward to buying my own livestock again. If luck holds out I will have at least one buffalo in good time,” says Ameenat.

Nourishing Futures with Sphere Standards

At Community World Service Asia, school meals go beyond filling plates; they nurture growth, learning, and well-being. As Sphere’s Regional Partner in Asia, we integrate Sphere food security and nutrition standards into our school feeding project, supported by PWS&D and CFGB, to ensure every child receives safe, balanced, and culturally appropriate meals.

Our approach focuses on:

- Assessing nutrition and food security to meet children’s real needs

- Preparing meals with locally sourced, balanced ingredients

- Upholding hygiene and food safety at every step

By combining care, local knowledge, and international standards, children are eating healthier, attending school more regularly, and thriving academically.

Because when meals are made with care, children learn better, grow stronger, and dream bigger.

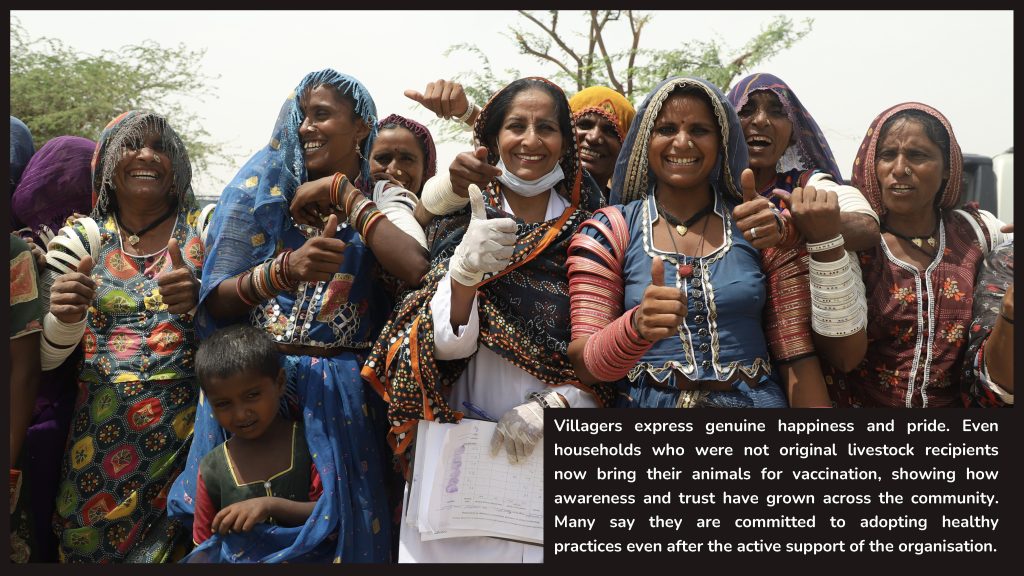

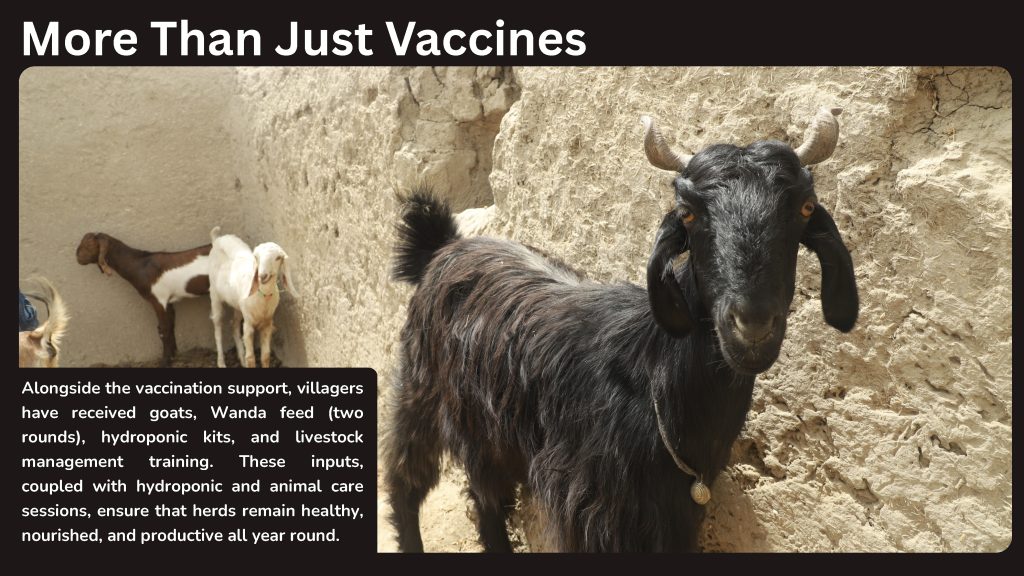

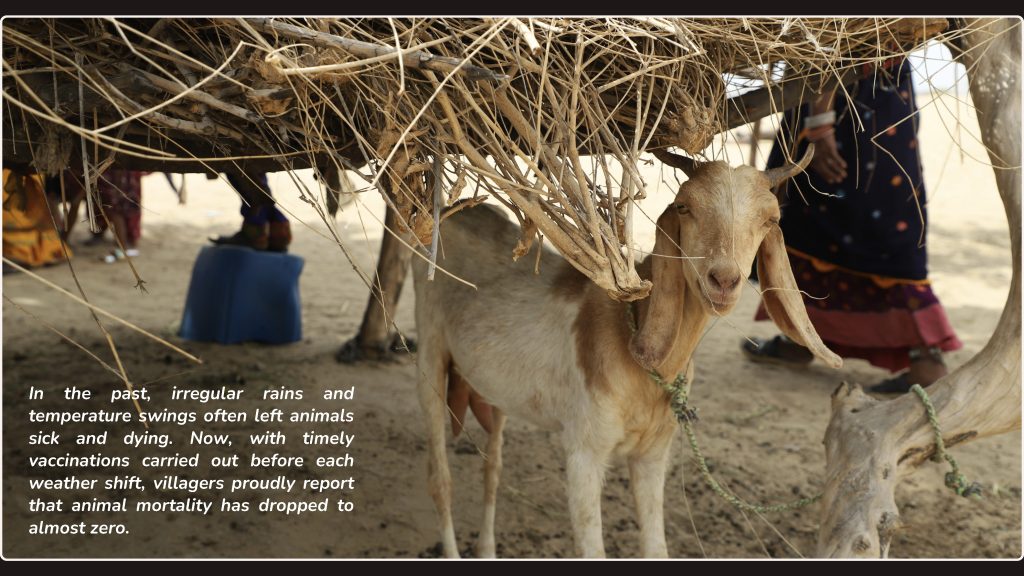

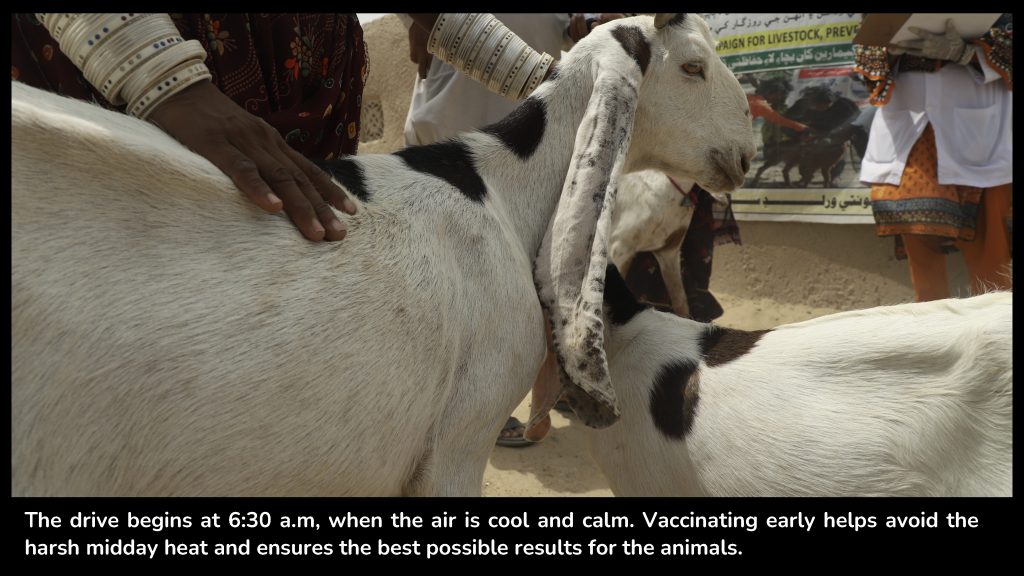

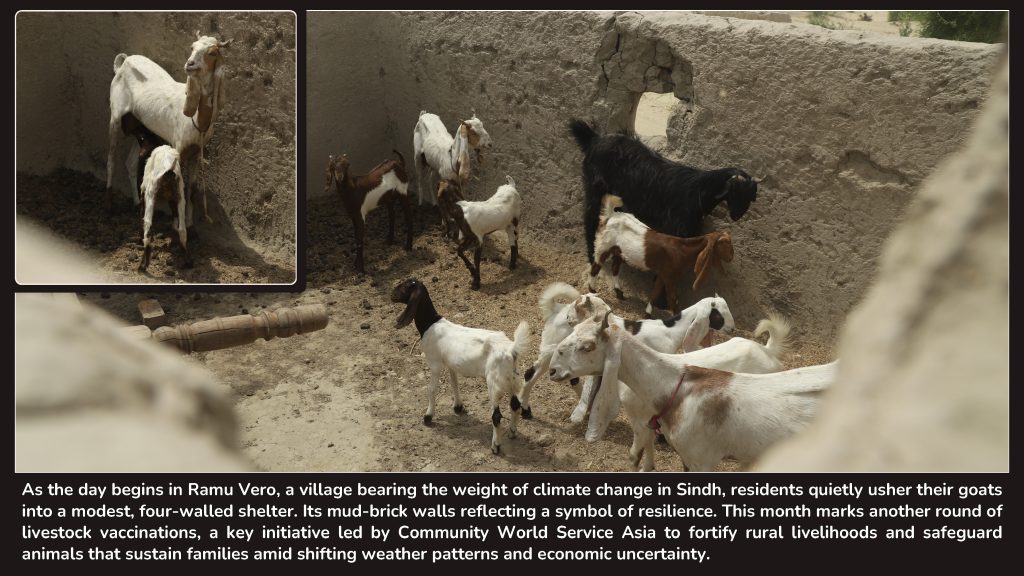

Livestock Assistance in Village Ramu Vero:A Healthier Herd, A Stronger Livelihood

A short walk to clean water

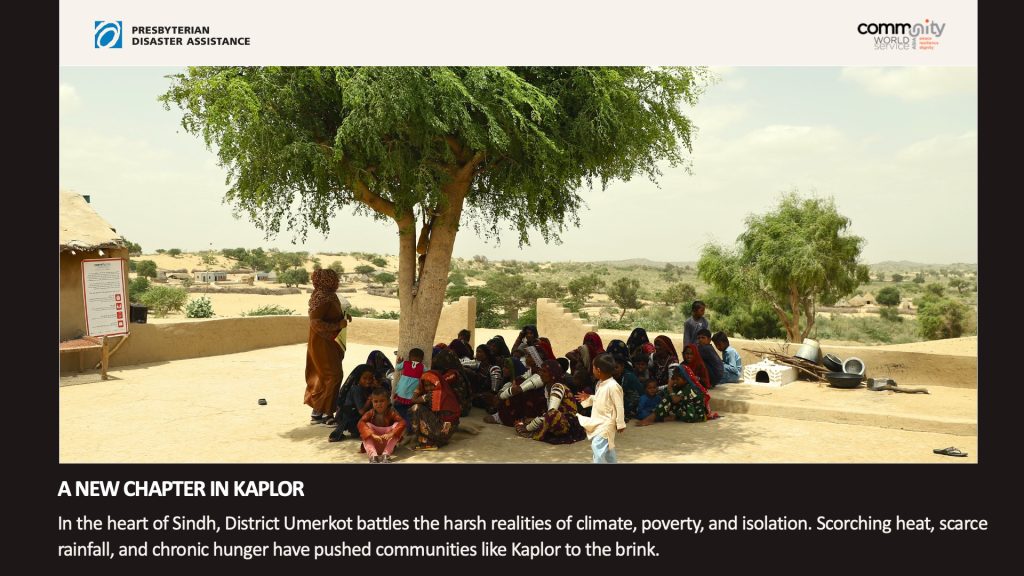

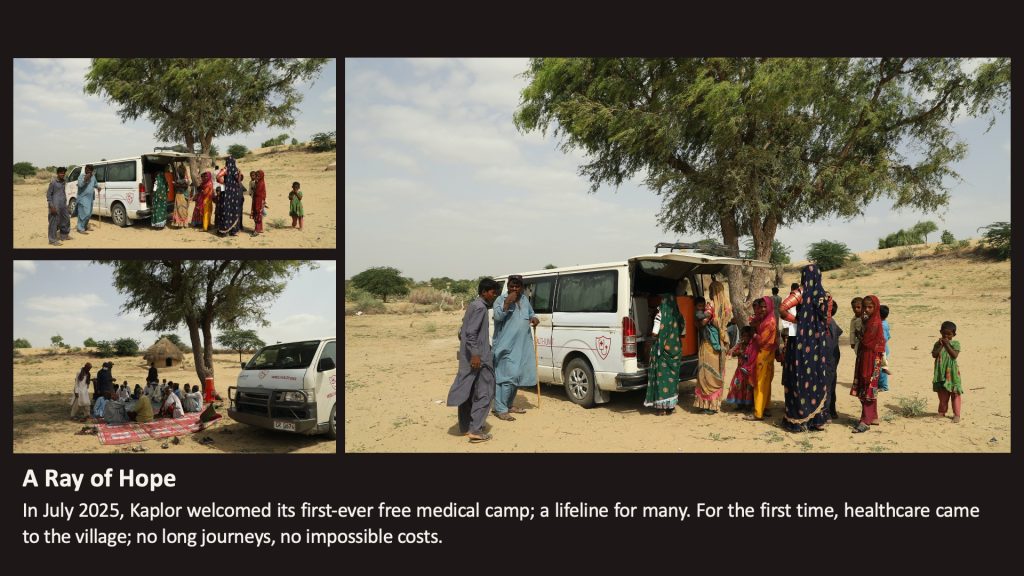

A new chapter in Kaplor

Sikander’s Story of Resilience: When the Waters Came, They Stood Together

Sikander, a farmer from Babu Syal in Umerkot, is regarded as a pillar of strength by his community; a place where the climate swings from relentless heat that scorches the earth to sudden, destructive monsoon floods. For the sharecropping families of this region, the land is more than just livelihood; it is legacy, sustenance, and survival. Protecting it is not a choice, but a necessity. Sikander understood this deeply, and when he recognised a recurring threat that others hesitated to confront, he chose action over silence.

Living with his mother, wife, children, and siblings, Sikander has long relied on farming to support his family. In 2011, torrential floods swept through Umerkot, leaving behind a trail of devastation. Homes were destroyed, fields submerged, and entire villages lost beneath rising waters. With no preparedness measures in place, communities were left vulnerable and exposed.

The floods of 2022 brought renewed crisis, this time on a national scale. Sikander’s village remained submerged for nearly three months, while surrounding farmlands stayed underwater even longer. The repeated trauma of these disasters galvanised the community. No longer willing to remain unprepared, they committed to building resilience and safeguarding their future.

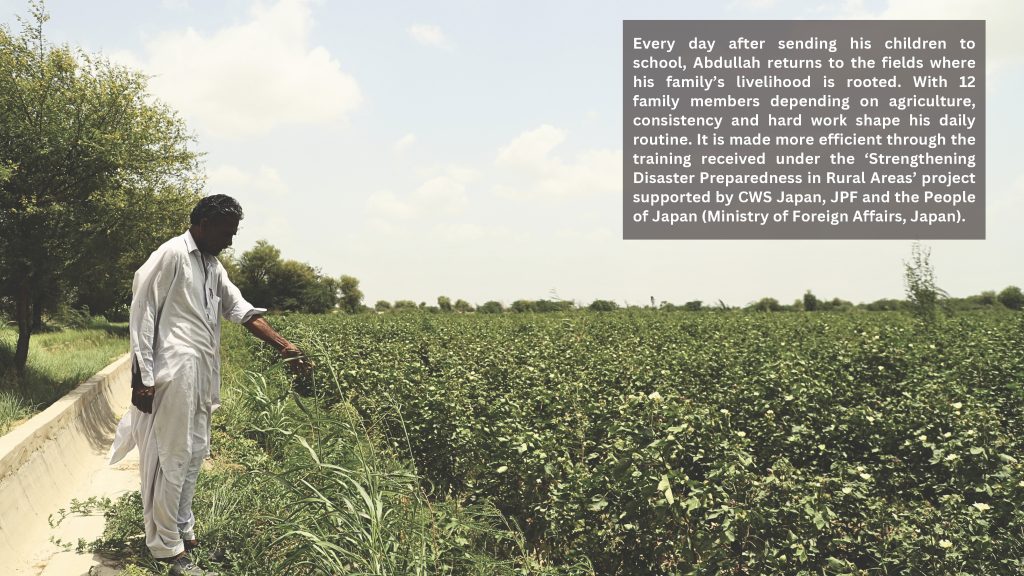

Through the support of Community World Service Asia’s disaster resilience initiatives, Sikander and his fellow villagers are now charting a new path; one rooted in preparedness, collective strength, and hope. In 2023, Community World Service Asia (CWSA) identified flood-prone regions of Umerkot and introduced disaster preparedness and climate change adaptation trainings. Sikander was among the participants and later joined the Disaster Risk Reduction Committee set up under CWSA’s initiatives supported by CWS Japan and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) Japan.

By the time the monsoon rains returned in 2024, Sikander, equipped with disaster preparedness training, emerged as a unifying force, rallying not only his own village but neighboring communities as well. For twenty consecutive days, they stood as the frontline against impending disaster, working tirelessly to safeguard their lands and livelihoods.

Under Sikander’s leadership, villagers mobilised every available resource; tractors, fuel, manpower, and even dipped into their own savings to sustain the effort. Men laboured without pause, clearing blocked canals and reinforcing embankments to redirect floodwaters. It was a remarkable display of collective resilience, where women played a vital role by preparing and delivering hot, home-cooked meals and fresh rotis to those working in the field from dawn to dusk.

True to the wisdom that prevention is better than cure, the community acted swiftly on early flood alerts, implementing proactive measures before the crisis could escalate. Their efforts paid off: thousands of acres of farmland and hundreds of homes were protected from destruction. Through the construction of barrier walls, strategic placement of sandbags, and careful management of drainage systems, they successfully averted catastrophic flooding.

Sikander also coordinated with the Livestock Department to ensure timely vaccinations, safeguarding animals from seasonal disease and further loss. His leadership reflects the power of community-led action, where preparedness, solidarity, and timely intervention can transform vulnerability into resilience.

When asked why they worked collectively instead of individually, the answer was simple, “Who could have achieved this alone? Why wouldn’t a person go to every length to save his home, his land, his life’s work? Every village was at risk. Every man had to take charge.” Sikander had long believed that the community’s unity would be their greatest defense against calamity. Even when others were hesitant at first, he persistently urged them to prepare for what lay ahead.

Sikander’s unwavering determination earned him the gratitude of his people. He recalls, “They spoke my name in their prayers and showered me with good wishes.”

Today, after participating in these training sessions, Sikander trusts his instincts and uses his courage to turn resilience into action. “We will not only use these techniques to reduce flood risks ourselves,” he says, “but also pass them down to our children. We cannot change the entire village system overnight, but step by step we are moving toward resilience.”

Parsan, the Go-Getter

Parsan Kohli, a bright and articulate young woman from the village of Cheel Band, stands out for her clarity of thought and speech, particularly in Urdu—a language she proudly says she learned from her schoolteacher father. At twenty-five years old, she has already been married for a decade and is the mother of four children. In a community where having eight to ten children is the norm, her decision to limit the size of her family is notably uncommon.

Smiling, she shares that her husband, Moolchand, is one of fifteen siblings, while gesturing towards her mother-in-law who they live together with. “For all the hard work that woman has done, she looks wonderfully unscarred,” she remarks. With a large family to support, it is unsurprising that Moolchand never had the opportunity to pursue an education and now works as a bricklayer.

What sets Parsan apart is not just her decision to raise a smaller family, but the reasons behind it. As an active member of the Village Management Committee (VMC), established in 2022 under Community World Service Asia (CWSA) and Act for Peace’s(AfP) Health and Education project, Parsan has gained new perspectives on health, personal care, and family well-being. She reflects that, prior to her involvement with the VMC, she had limited understanding of basic hygiene and health issues. Like many others, she once believed that having more children was a way to secure the future. However, she now recognises that larger families often deepen the cycle of poverty. With this knowledge that she gained through the Health and Education Sessions held through the course of this project, she has become a vocal advocate for informed family planning within her village.

“But I had to begin with my own household,” she says. “I had to set an example before encouraging others to follow.” She recalls that it was once common in her village for women with infants as young as six or nine months to be pregnant again. Over the past two years, however, Parsan has played a key role in shifting this norm. She has supported nearly every woman in her para (neighbourhood) in adopting healthier spacing between children. The long-standing tradition of frequent, back-to-back pregnancies is now largely fading.

Her efforts particularly focus on newly married young women, to whom she gently explains the importance of waiting before expanding their families. Though she has not kept exact figures, Parsan believes at least thirty women have embraced her message, with ten of them committing to having smaller families. “They understand now that large families perpetuate poverty,” she says.

During her most recent pregnancy, Parsan experienced unusual discomfort. Remembering the health guidance sessions conducted by CWSA staff through the VMC, she visited the local Health Unit for a check-up. There, she discovered that her haemoglobin level had dropped to eight. She received treatment in time and went on to deliver a healthy baby. “Had I not attended those sessions, I would never have known. Who knows what could have happened,” she reflects.

Parsan sees her most significant achievement as her success in promoting girls’ education. Just two years ago, only twelve girls in her community were enrolled in school; today, that number has risen to thirty-five. Some of these girls are ten years old and only now entering grade one, underscoring how delayed school enrolment had become. She explains that girls’ education was often seen as unnecessary, with daughters expected to assist with domestic tasks. Even boys were sometimes kept home to fetch water while the older men idled. Going door to door, Parsan urged mothers to send their children to school, stressing that government schools do not charge tuition. “Your only expense is a few rupees for notebooks and pencils once every few months,” she told them.

Gradually, the number of enrolled children began to grow. With children now in school, Parsan notes that men have become responsible for fetching water, something that was once seen as children’s work.

The school in her neighbourhood, which serves approximately 200 households, now has four teachers. Two are funded by CWSA & AfP, one by the local community, and one by the government. Previously, families would often cite a lack of teachers as a reason not to send their children to school. That barrier, Parsan says with satisfaction, has now been removed.

Parsan is also deeply committed to preventing early marriage. “Fourteen is the usual age for marriage here, I myself was only fifteen,” she shares. Recently, she managed to delay the wedding of a sixteen-year-old girl through community engagement. The parents have now agreed to wait until their daughter turns eighteen. With so many accomplishments, what lies ahead for Parsan? She simply says she will continue. “Children are being born who need to be educated, and they must not marry until they are of legal age. I have to ensure that the right thing is done, that they stay in school and don’t marry before eighteen.”

Shelter, Wheat, and Hope: How Lakshmi Invested in Her Family’s Future

Married at the age of 17, Lakshmi assumed the weight of household responsibilities early in life. With her husband, Laalu, working as a labourer in the city to support the family, Lakshmi remained the steady anchor at home. Together, they raised four young children, three sons and a daughter, all between the ages of five and ten. Despite limited resources and daily challenges, Lakshmi nurtured a modest but fulfilling life, grounded in resilience and the warmth of her family.

Five years ago, Lakshmi’s world was turned upside down when her husband, Laalu, tragically passed away after a snake bite. Fate did not give her a chance to fully grieve the loss of her partner. Overnight, she became the sole caregiver and breadwinner for their young children, forced to navigate an uncertain and demanding future entirely on her own.

Now 32, Lakshmi continues to shoulder the full responsibility of raising her family. To survive, she and her children work together as labourers in fields of Village Lakho Kolhi, striving each day to meet their most basic needs.

In 2021, driven by quiet determination, Lakshmi took a bold step to improve her family’s future by breeding two goats, establishing a modest but stable source of income. It was a turning point that promised a path toward self-reliance. However, less than a year later, the catastrophic floods of 2022 swept across Pakistan, displacing thousands and claiming countless lives and livestock.

Lachmi’s village, Lakho Kolhi in Umerkot, was among the hardest hit. The deluge reduced homes to rubble and left the community submerged in devastation, erasing what little security they had built. Lakshmi and her family lost their most treasured possession, their home, and faced a heartbreaking reality. The destruction was so extensive that rebuilding was impossible. With no other option, they were forced to flee and start over, carrying with them only resilience and the will to endure.

With nowhere to go, Lachmi and her children found themselves in her brother-in-law’s house, who himself had relocated to village Anwar Pathan with his family in search of safer grounds. In a time when everyone around them was grappling with uncertainty and hardship, his support was both rare and deeply meaningful. Within that borrowed shelter, Lakshmi tried to rebuild a sense of home for her children, even as daily survival weighed heavily on her mind. The question of how to feed her family was a constant worry, one that echoed the broader struggle shared by countless families, especially single mothers, facing the aftermath of displacement.

Living in someone else’s home brought a host of challenges for Lachmi, from compromised dignity to concerns over safety and protection. She endured mistreatment and a lack of respect from the household members, all while carrying the weight of worry for her children’s well-being.

In the aftermath of the devastating floods, Community World Service Asia (CWSA), in partnership with Presbyterian World Service & Development (PWS&D) and the Canadian Food grains Bank (CFGB), launched a Cash for Food initiative aimed at restoring dignity and choice to families like Lakshmi’s. The program provided unconditional cash assistance of PKR 20,000 per month for three months, March, May, and June 2025, empowering flood-affected households to address their food security based on their specific needs.

With the first installment, Lachmi prioritised her family’s stability. She spent PKR 10,000 (USD 35) to buy wheat flour, to ensure a reliable supply of food in the weeks ahead. Another PKR 6,000 (USD 21) went toward repaying a debt she had incurred just to feed her children, a financial weight she had long carried. The remaining PKR 4,000 ( USD 14), was carefully allocated to purchasing sugar, rice, and vegetables, allowing her to provide balanced nutrition with renewed peace of mind. In a move that reflected both vision and resilience, Lakshmi used the second installment to purchase two young goats, an investment in future sustainability. As the goats grow, she plans to sell their milk locally, establishing a modest yet dependable source of income for her household..

With the third and final cash installment, Lakshmi embraced a moment of joy amidst hardship. She lovingly chose new clothes for her children, spending nearly PKR 5,000 ( USD 18) on new clothes for them to bring smiles and a sense of normalcy to their lives. The remaining PKR 15,000 (USD 53) was set aside to secure their food supply, a deliberate decision rooted in maternal foresight. “Even if we have nothing else,” Lakshmi shared, “we should have wheat in the cabinets, so we never go to bed hungry.”

Lachmi has courageously shared her journey with others, inspiring many through her resilience and determination. “Now we’re finding new ways to support our families,” she said. “Many women in our village have stepped up to help, especially after losing their livelihoods.”

Part of the funds also went toward purchasing medicine for her seven-year-old Gulji, who lives with epilepsy. Reflecting on how she used the assistance, Lachmi said, “The aid is temporary, and the money is meant to end someday. To truly benefit from it, I had to invest it with purpose.”