comms

Training on: Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management

When: 14th-16th November, 2023

Where: Peshawar, KPK

Language: Urdu & English

Interested Applicants Click Here to Register

Last Date to Apply: 10th October, 2023

Rationale:

In an era defined by dynamic shifts in development and humanitarian approaches, the essence of community engagement has taken on global significance, both upstream and downstream. This evolution has reshaped how we conceptualize, plan, and gauge impact within the ever-changing world ecosystem.

The “Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Management Training” emerges as the compass guiding professionals through the intricacies of modern impact assessment, along the project plan. By unearthing advanced methodologies, pragmatic frameworks, and illuminating case studies, this training empowers participants not only to measure impact but also to strategically align interventions for comprehensive community advancement objectives.

Training Objectives and Contents

This program is about navigating the entire project lifecycle with finesse. From meticulously crafting program design to seamless implementation, rigorous monitoring, and impactful assessment, we encompass ensuring that projected outcomes become documented realities.

By joining this training, the impact of your interventions becomes your ally, from inception. Discover how to harness cutting-edge data collection and analysis tools that empower your impact measurement. Our training doesn’t just stop at knowledge – it’s a bridge to practicality. Real-world exercises, tailored to the times with social distancing in mind, weave seamlessly with expert lectures and the invaluable exercises for experience sharing by eminent leaders in the development and humanitarian sector. With post-training coaching and mentoring bolstering 30% of participant organizations, your growth is our relentless pursuit. Dive into the heart of impact management as we delve into:

- Mastering program design with an impact and learning lens

- Commanding Theory of Change/Change Models for dynamic interventions

- Immersing in a spectrum of impact measurement and evaluation tools, from data and tech powered analysis solutions to remote data collection innovations

- Fusing Quality and Accountability standards with humanitarian programs, forging a path of excellence

- Pioneering peer support action plans and nurturing coaching/mentoring avenues

Number of Participants

We encourage you to join an exclusive group of 20 change-makers, by accepting applications from diverse backgrounds, including women, differently abled individuals, and aid workers from ethnic/religious minorities. Priority is given to those from under-served areas. Deadline to Apply is by October 10, 2023.

Selection Criteria

- Primary responsibility for monitoring and impact assessment /MEAL staff at the project

- and/or organizational levels

- No previous exposure/participation in trainings on Monitoring and Evaluation for Impact Measurement

- Mid or senior level manager in a civil society organization, preferably field staff of large CSOs or CSOs with main office in small towns and cities

- Participants from women led organizations, different abled persons, religious/ethnic minorities will be given priority

- Willing to pay a fee PKR 20,000 for the training. Exemptions may be applied to CSOs with limited funding and those belonging to marginalized groups. Discount of 10% on early registration by 05 October,2023 and 20% discount will be awarded to women participants

About Community World Service Asia

Community World Service Asia (CWSA) is a humanitarian and development sector organization, registered in Pakistan, head-quartered in Karachi and implementing initiatives throughout Asia. CWS/A is a member of the Core Humanitarian Standard (CHS) Alliance, a member of SPHERE and their regional partner in Asia and also manages the ADRRN Quality & Accountability Hub in Asia.

Facilitator/Lead Trainer: Mr. Mohammad Tayyab

Mohammad Tayyab specializes in planning and accountability measures of projects and programs within the development and humanitarian sectors. With over 20 years experience of working for development sector projects, programmes and institutions, and a strong background in designing and conducting social research and MEAL assignments, he has successfully contributed to the sector in Pakistan and in other countries. He has evaluated the impacts of programs, synthesizing lessons learned, and fostering a knowledge management culture to empower institutions.

One of Mohammad’s key strengths within the MEAL processes is his ability to effectively engage with diverse stakeholders, both individually and in group /institutional settings. His work has also played a pivotal role in facilitating organizational development for a wide range of international and national NGOs, bilateral and multilateral organizations, as well as corporate companies. In addition to his project and program planning expertise, Mohammad has conducted extensive research in social and institutional aspects. His research encompasses a broad spectrum, including public sector institutions, corporate companies, and social organizations. Within his area of expertise, which includes climate change, livelihood, gender, DRR and humanitarian response, he has particularly excelled in enhancing institutional and program effectiveness within these domains.

Medical Aid: Not a Day too Soon

Medical Aid: Not a Day too Soon

Village Dharshi Bhagat lies by the road connecting Samaro town with Samaro Road; the latter being the town’s railhead where the old abandoned metre-gauge railway station still stands for the first two weeks after it started in late July, the rain did not stop for a minute. Thereafter it continued to teem down with brief intervals lasting never more than some minutes until the village went under a metre of water.

Twenty-five-year-old Heeru was only days from delivering her baby when it started. As the water rose, she and some other women made a desperate run to save whatever little cotton they could from the fast drowning field they had so carefully tended the land they worked as labourers. The struggle in mud and water was worth only a few thousand rupees.

With the village going under water, she and her family left their home and the fields and moved to the only stretch of road that was above the dark water. For three months, they lived under a makeshift shelter of bamboo poles holding up plastic sheeting for a roof. It was good fortune that Heeru had salvaged some cotton and there was some cash for food because in the time of the rising waters, she gave birth to her second child, a daughter. When her pains began, her husband hired a motorcycle and ferried Heeru to the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road where she fortunately got the attention of the doctor and a safe delivery.

Not long after the birth of the child the meagre cash in her kitty ran out and her family subsisted on chilli paste and roti. Their one goat provided a small amount of milk daily. It was a hard life for the family, especially so for the young lactating mother.

Heeru recounted how her firstborn, a son, had died two years ago aged just four months. The child had gone down with fever and convulsions and though the Basic Health Unit at Samaro Road was just 4 km away, the parents were tardy in taking him there. For five days the poor child suffered and when they eventually did get to the BHU, the doctor could do nothing to save the baby.

For some inexplicable reason, seeking medical assistance was simply not a priority for these poor people. They still relied on folk medicine and even considered milk tea some sort of panacea.

Dharshi Bhagat, who gives his name to the village, said Heeru’s husband was lucky to be able to rent a motorcycle because shortly after, the only transport capable of plying on the submerged roads were big four-wheel drive vehicles. An ailing person had to be carried either on a string bed or piggyback all the way to the units either in Samaro or Samaro Road. And this was a time of rampant disease. Fever, skin infections and diarrhoea were raging in the makeshift camp strung out along the road. In that desperate time of zero income, men were seen carrying the ailing to the BHU.

In mid-October, the first Community World Service Asia’s medical mobile unit reached this village. The village was still submerged and the mobile unit had to be parked on the road, the only strip of land free of water. Dharshi Bhagat said this came not a day too soon for who would not have appreciated this gratis service at the doorstep in that time of great adversity.

Lady Health Visitor Farkhanda said the mobile unit had been on the road for ten weeks moving from village to village and treated on average a hundred and fifty patients every day. On the first visit to Dharshi Bhagat, they had a similar number between nine in the morning and three in the afternoon. Referrals of more complicated cases was made to the Samaro town hospital. Common complaints were malaria, water-borne gastro-intestinal, eye and skin infections. This time around, respiratory tract infections had increased and the demand was for ‘pills for strength’, as multivitamin tablets are referred to.

Outside, among the crowd of men waiting to consult the doctor Bhoomo said he felt weak and his ‘liver burned’ and showed a handful of blister-packed multivitamin tablets and an antacid.

“The first time the medical van visited our village, I was suffering from the same, but I had been out cutting mesquite to sell in neighbouring villages and I missed my chance to see the doctor,” said Bhoomo. For him his suffering was secondary. Most essential was for him to make some little cash for food.

Why hadn’t Bhoomo gone to the hospital in town during all this time? “I have no money, the fare out and back is Rs 40, and after I spend a day cutting mesquite, there is only enough cash to purchase food for my family of nine. I cannot afford to go to town.”

On the second visit in mid-November the mobile health unit had in just two hours treated one hundred and thirty patients. And an equal number waited patiently outside. Some like Dheero said they had no complaint and had come only to watch the goings on; most others complained of stomach ache and fever. Nearly all of them had either simply suffered stoically or experimented with folk medication to no effect. The lament was the same all around: they had no money to visit the hospital in town. And they could not afford to take time off from their struggle to earn some money.

Listening to the very vocal Kasturi, suffering in silence seemed to come naturally to them. She had a reasonable income from working as a seamstress while her husband was a door-to-door clothier. Their once comfortable life was now reduced straitened circumstances.

“The crops have all been destroyed. There is no work and therefore no money. Who can order new clothing in these times? The Lord is kind, I took great precautions and my three children did not fall ill, but families with illness could either feed themselves one, or at most two, meals a day. They did not have the means to make frequent trips to the Samaro hospital.”

Dharshi Bhagat was right: the mobile unit had come not a day too soon.

One Year of Recovery: Remembering Flood Survivours & The Road Ahead

A year on, Tooba Siddiqui, highlights how CWSA has worked towards mainstreaming quality, accountability and Safeguarding in flood response activities in Pakistan.

Moolo: man of the house

If the humanitarian food aid programme1 of CWSA favoured someone at just the right moment in their lives, it was old Moolo and his wife Babbri. In April 2022, shortly after this family had received the first aid package, Moolo had complained of failing eyes. But he and indeed others too thought it was only the usual age-related problem. Sadly, it was worse than that.

Back then, Moolo had suffered a setback because of the failure of the summer crop of 2021. The loan he and his son Chandan had got for agricultural input was lost and they were under debt. To make matters worse, in the absence of medication, Chandan’s epileptic fits got more frequent. But with food on loan, there was no cash for health care.

Then came the CWSA aid and with food taken care of, the old couple were able to provide the much needed daily dose of medication to their son. However, even as the young man’s health improved, old Moolo’s eyes deteriorated. With that, his speech was becoming increasingly unintelligible and his mind clearly slowing down.

A difficult life of poverty and privation had taken its toll for though he was barely into his seventies, Moolo was completely spent.

The idea of the little store he and Babbri had planned to open from the saving they would make because of the food aid, began to recede into the distance. Why, how was Moolo, now unable to go about unaided, to manage the store? Ever more difficult, how was he to go into town unattended to purchase supplies needed to keep the store going?

His wife Babbri, though just a few years younger but much more spry, became the person of the hour. She went ahead with the opening of the store which was nothing more than a variety of children’s snacks, a few packets of condiments and the unfailingly ubiquitous packets of cigarettes.

In early February 2023, just months after the last of the food packages had been received and consumed, Moolo was reduced to just a presence around the house: his eyes had finally given way and people around him were only unrecognisable shadows; only light and darkness were still clearly discernible. But the little store he had dreamed of was functioning out of the tin trunk and children of the village were frequently in and out of the compound picking up things against cash.

The question then was how was he managing the store with his disability? But before Moolo could respond, Babbri spoke up.

“He cannot do it now. I run the store and I net a daily profit of PKR 300 (Approx. USD 1),” she said. “Nobody gets credit from my store,” she added with a grin.

She related that the store was started shortly before the deluge of July 2022 with an investment of PKR 1000 (Approx. USD 3). In February, Babbri had stocks of PKR 3000 with PKR 4000 (Approx. USD 14) in hand to replenish her store. She was due to visit town with her cash to purchase supplies as she had been doing over the past seven months. And she was doing it all by herself. In effect, she was now the man of the house.

Asked how the food aid helped her and her family she was unequivocal: “It is because of this aid that we are not under debt. The little field we had planted as sharecroppers last summer, sprouted well enough. But with two straight months without a single day of sunshine and incessant rain, the crop withered. We were going to be without food and would have been forced to borrow money to keep body and soul together. Or we could have sold our goats to pay for food. But we are not under debt and we still have our goats!”

She related that three goats with three kids was a right little fortune in this Bheel village of poor folks. That means the family had their own milk for tea. And there was a time before 2022 when in years of poor harvest they would have only black tea.

The wheat harvest in ‘Sindh’, as the people of Thar differentiate the fertile canal-fed area from their rain-dependent desert, was drawing near, said Babbri. She and Moolo together with their two sons had migrated every March to participate in the harvest and returned with some 500 kilograms of wheat as their wages. This lasted them some four months until the millet and guar harvest was brought in.

But with Moolo’s deteriorating eyes and Chandan’s epilepsy, only Babbri and her younger son participated in the harvest in 2022. Now because Babbri will be minding the store, the responsibility of bringing home the wheat rested upon Chandan and his wife. They would be leaving in early March to be away for four or five weeks. If they work hard enough and Chandan takes his medication on time, they will bring home 400 kilograms of grain. The younger son who works on road construction sites, will remain back so that his daily wages provide the much needed cash to Babbri and the invalid Moolo.

But if Babbri were to also migrate to participate in the wheat harvest, there would be more than the anticipated wages.

“I cannot leave Moolo alone in his condition,” said the spirited woman. “I have to cook for him and look after his other needs. And then who will tend to the shop and purchase supplies?”

Ever mindful of her responsibility, Babbri pointed out that Chandan will be sent away with six weeks’ worth of his epilepsy medication. And that would cost about PKR 1000. Before the food aid, Chandan had suffered and with him the whole family because there had never been enough cash to provide the daily dose.

As for the future, Babbri was very clear in her mind. “If I have some more money, I’ll invest it in our store. But for the time being I am very satisfied with the way it is going.”

- Humanitarian, Early Recovery and Development (HERD) program

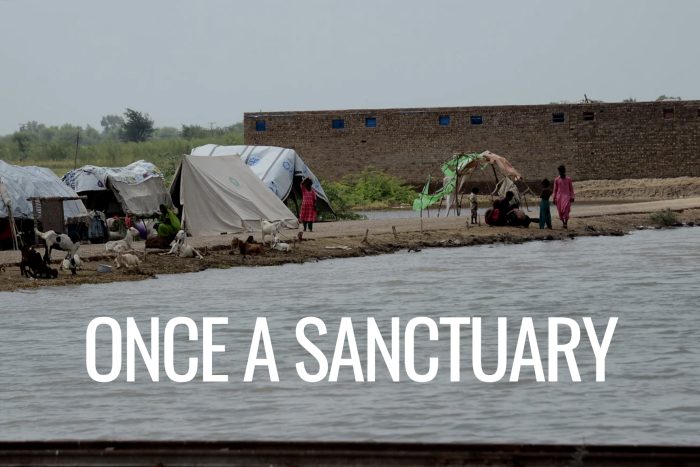

Once A Sanctuary

One Year of Recovery: Remembering Flood Survivours & The Road Ahead

ACT Alliance has been one of CWSA’s key partners in humanitarian response in the region. Their support ensured aid to thousands of flood affected families in Pakistan in 2023. ACT staff was in the field this month to monitor relief and response activities supported by the Appeal with a special message on the first anniversary of the disaster.

One Year of Recovery: Remembering Flood Survivours & The Road Ahead

As we mark the one year anniversary of Pakistan’s devastating Floods of 2022, our Regional Director, highlights how affected populations have survived one of the century’s worst climatic disasters and the needs that still exist.